Contents

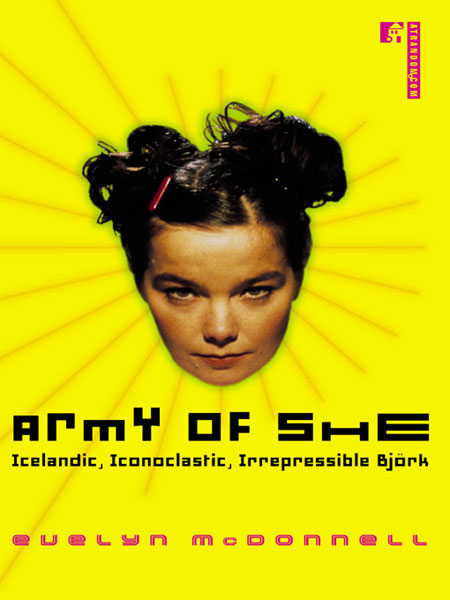

TO

MUSIC

LOVERS

PREFATORY EPISODE

In which the narrator explains the whole e-Bjrk concept, and falls in love with a sound

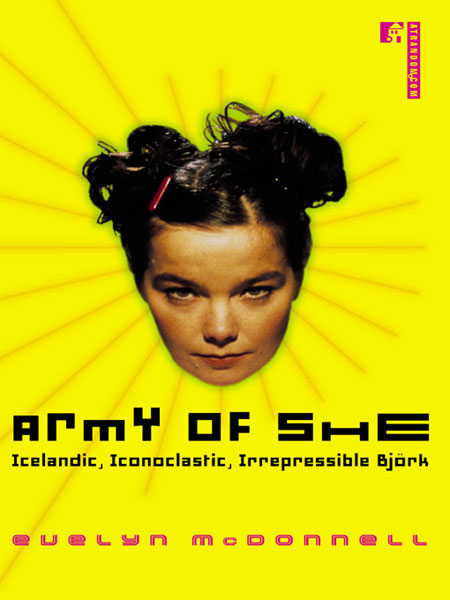

Bjrk Gudmundsdttir was about twenty years into her career before I liked her. This places me somewhere in between the two groups of people most likely to be reading these words: those of you who heard about the numerous awards and award nominations for her role in the film Dancer in the Dark, promptly said to yourselves, What is this thing called Bjrk? And why is she wearing a swan?, and conducted the appropriate web searches; and those of you who are Bjrkophiles, collectors of her every white-label remix and guest vocal appearance, connoisseurs of all things Bjrkeven e-books by comparative greenhorns.

This is not a biography. No interviews were conducted especially for it, no new information worth bragging about is revealed, long blocks of time and pieces of work (those excruciatingly jaunty Sugarcubes tracks) are completely skipped over. An excellent, detailed, thoughtful overview of the artists life up until 1996 has already been presented by English journalist Martin Aston in the book Bjrkgraphy. Although it is somewhat out of date and sadly out of print, if thats the kind of thing youre looking for, then this is another perfect illustration of why AmazonNoble.com will never replace the beautifully musty haven of used bookstores. Turn off the computer and dust off those dustjackets!

This is something else: yes, a new hyped new media new technology with a cute marketing name that makes e-fficient, e-conomic use of that ubiquitous electronic-age, neologism-friendly, monosyllabic prefixladies and gentlemen, an e-book. I think of it as an endeavor as retro as techno (a very Bjrkian balance, by the way: see E-pisode 3), the resuscitation and revitalization of a genre that had become ghettoized as the sole province of (gasp) scholarly types, the return of the thumbsucker special: an e-ssay. My say, on why a woman-child from the island nation of Iceland is the most interesting, the most important, the most innovative, and the most engaging musical star of our precipitous, capricious times.

If you dont know a thing about Bjrk except her gutbucket performance in Dancer in the Dark, then hopefully this piece of writing will show you the wild landscape of her pop, fashion, and moving-image forest without knocking you out on the pesky trees of detail. If you know everything about Bjrk, then maybe this will change your mind: put her into perspectives you hadnt thought of, make you reevaluate aspects of her life you had taken for granted, give you some arguments with which to justify your obsession to concerned parentsmake you more crazy about her than ever.

It may have taken me twenty years, but Im a fana skeptical critic converted by music so spectacularly intimate, it feels like breath. I think of Bachelorette, a love song from the 1997 album Homogenic that has a tango bassline and Puccini-worthy lyrics of passion (by Icelandic poet Sjn), and it instantly lodges in my throat, residing midway between pulmonary central and nerve headquarters, until I want to exhale it out or suck its oxygen in from scalp to toe. A song can inhabit you, until you expel it in voice or let it send you spinningsing or dance along.

In August 1997 I interviewed Bjrk for a cover story for the music magazine Request, published when Homogenic was released, as the saying goes (as if it had been held captive). I was at that point at least curious and respectful of her work, having gotten over my early annoyance at the bewitchingly pedophilic appeal of her childlike manner. And I was growing more in love with Homogenic with each headphones listen as my plane flew into Iceland. My advance copy of the album (ultimate rock-crit perk) had arrived the same day I took off from Minneapolis, and so I spent the flight cramming to understand her.

Music can mark time, and vice versa. The process can be as simple as Big Chill nostalgia: We like a song because we heard it when we were falling in love, or having a good time at a party, or lost in delirium on the dance floor. When we hear the song later, even years later, it takes us back to those memories: Its a trigger, a madeleine, a remembrance of flings past. Or the connection can be more serpentine. Events and melodies can influence each other, the tone of a song becomes the color of our experience, we adjust the pace of our bodies to the rhythm that repeats itself in our head, then suddenly were soaring up the road in a burst of strings or crashing like cymbals into bed.

What do I mean by we, kemosabe? I certainly dont intend it as the royal we. I suppose Im hoping its a communal we, that Im describing a basic human experience, that music really is the universal language. Or maybe Im just speaking for my tribethe certain brand of people, including herself, that Bjrk told Flaunt magazine she was defending with her portrayal of Selma in Dancer in the Dark: one of those people who hears music all the time in their head, from like, one year oldthey may be with ten other people but all theyre hearing is this kind of soundtrack.

Homogenic quickly became part of my soundtrack, beginning on the plane as it wheeled over the Arctic and I stared out the window at Greenlands white, white glaciers reflected in blue, blue waters, a vision from a million TV screens that was even more impressively Technicolor in real life, a moving landscape being scored for me by Bjrks equally vivid and dramatic soundscapes. This was a repeat of a primal experience for me: Ever since I was a kid riding in a car on cross-country summer vacations, Ive sat looking out of windows with songs in my head, musical daydreaming between destinations. Ive loved music ever since I can remember; say three sentences to me and Ill find a song lyric in them, Im that certain brand of people.

In 1997, musical daydreaming was something I repeated over and over, traveling out of my Manhattan home a dozen times in as many months. The year had started with an uprooting: I had moved to Florence to be with my husband, only to have him kick me out two weeks later. Temporarily homeless, I traipsed from Belize to Michigan to L.A. to Reykjavk, learning to reanchor myself to the music in my head wherever my hat found itself.

So the opening lines of Homogenic struck a nerve: If travel is searching / and home has been found / Im not stopping, Bjrk sings in a tremulous whisper over a rippling electronic drum and warbling, synthesized strings. Hunter blends the aching live sound of the Icelandic String Octet (orchestrated by Eumir Deodato, the Brazilian Quincy Jones, best known for the early-seventies hit 2001: A Space Odyssey), Yasuhiro Coba Kobayashis mournful accordion, and stuttering computer beats and beeps programmed by Brit brainiac Mark Bell. Tying the whole shebang together is Bjrks vocal: full of reverberating menace and trepidation on the verses, then bursting into full-throated confession, layers of her voice pitching next to each other then cascading together. The music swells like stormy waves, then eases back, but each crash is a little more threatening, each ebb more fragile, until the song fades out uncertainly, a threat not delivered but not rescinded either, not stopping. The lyrics hint at a failed relationship; its not clear if the singer is hunting for someone new, or someone old. The rest of the album, youre not sure if youre in her sights.

Next page