TAXING DEMOCRACY

In memory of

Leslie Whittington

(1955-2001)

Taxing Democracy

Understanding Tax Avoidance and Evasion

Edited by

Valerie Braithwaite

The Australian National University, Canberra

First published 2003 by Ashgate Publishing

Published 2016 by Routledge

2 Park Square, Milton Park, Abingdon, Oxon OX14 4RN

711 Third Avenue, New York, NY 10017, USA

Routledge is an imprint of the Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

Copyright Valerie Braithwaite 2003

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publishers.

Notice:

Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

Taxing democracy : understanding tax avoidance and evasion

1. Taxation - Australia 2. Tax collection - Australia 3. Taxpayer compliance - Australia

I.Braithwaite, V. A. (Valerie A.), 1951

336.2'05'0994

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Taxing democracy : understanding tax avoidance and evasion / edited by Valerie Braithwaite.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-7546-2243-6

1. Taxation--Australia. 2. Tax evasion--Australia. I. Braithwaite, V. A. (Valerie A.), 1951

HJ3091.T39 2003

336.2'06'0994--dc21

2002036105

ISBN 13: 978-0-7546-2243-7 (hbk)

ISBN 13: 978-1-138-26403-8 (pbk)

Chapter

A New Approach to Tax Compliance

Valerie Braithwaite

In the late 1990s, the Australian Taxation Office (ATO) underwent a series of reforms that set the stage for a new proactive role in building a voluntary taxpaying culture. The evaluation of these measures is being undertaken rather more systematically than reforms in other countries, with results that have implications for all nations' tax regimes. This process of reform is built on the premise that although legislation is one of the basic building blocks for compliance, it is far from sufficient. Tax law is contestable; it is also complex; and it is not beyond the initiative of taxpayers to avoid and evade tax in ways that are costly, both in terms of revenue that will never be collected and enforcement that is resource intensive. The traditional tax infrastructure of law, auditors, penalties, debt collectors, and court cases needs to be supplemented by measures that boost taxpayers' commitment to paying tax with or without the tax authority watching over their shoulders.

At the heart of the reform strategies of the late 1990s was the building of a relationship with the Australian community in which the tax office was to be (a) professional, responsive, fair, open, and accountable in helping taxpayers comply with their tax obligations; as well as (b) effective in bringing to account those who intentionally avoided their obligations. Through adopting such practices, the intent was that the tax office earn (c) the trust, support and respect of the community (Australian Taxation Office, 1997).

The first initiative toward building this relationship was the Taxpayers' Charter (Australian Taxation Office, 1997). The Charter articulated 12 rights of taxpayers and committed tax officers to treating taxpayers fairly and reasonably, to explain decisions, assist with questions, and provide reliable information, to respect taxpayer privacy, to keep the taxpayers' compliance costs to a minimum, and to be accountable, if necessary, through independent review. The taxpayers' obligations, articulated also in the Charter document, were four-fold and involved being truthful in dealings with the tax office, keeping records in accordance with the law, taking reasonable care in preparing tax information, and lodging tax returns and required documents by the due date.

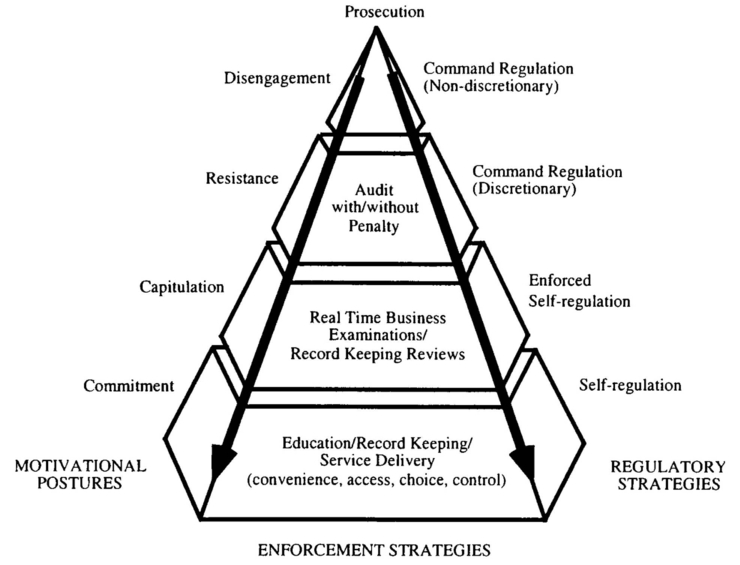

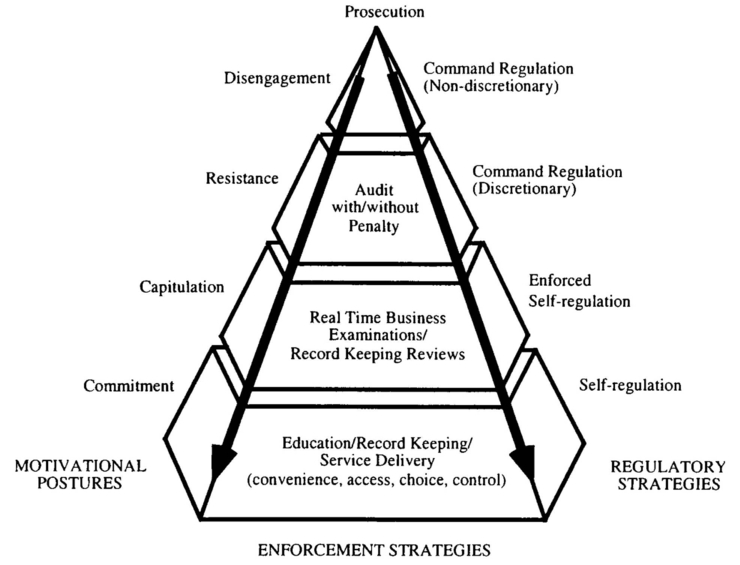

Bringing the Charter to life was no small challenge for the Australian Taxation Office. The traditional regulatory style of the ATO has been heavily weighted toward command and control with the automatic application of penalties for various forms of non-compliance (see the Compliance Model drew on the work of regulatory scholars at the Australian National University as well as on the vast research literature on tax compliance. Consistent with this literature (see Coleman and Freeman, 1997, for example), the Task Force urged the ATO to better understand not only the business profiles of taxpayers (which auditors traditionally, if partially, do), but also the nature of the industry they belong to, the economic factors that impinge on that industry and society more broadly, and the psychological and sociological factors that frame taxpayers' decisions or non-decisions about the actions they will take to meet their tax obligations. In the words of the Task Force:

none of these factors stand alone as the sole reason for a taxpayer's behaviour, and equally, it is not possible to identify which factors in combination may influence the behaviour of any one particular person. However, it is possible to identify a combination of factors that is more likely to influence behaviour for certain categories of taxpayers (Cash Economy Task Force, 1998, p. 20).

Better understanding of the complexity and interrelationships of factors shaping taxpayer actions was accompanied by an implicit distinction in the Cash Economy Task Force Report (1998) between the detection of non-compliance and the management of non-compliance. The detection problem involved identifying those among us who will be non-compliant. The human management problem involved nudging those of us who are non-compliant toward compliance, 'without adversely affecting compliant taxpayers' (p. 22). The Cash Economy Compliance Model was constructed to provide a methodology for addressing the human management problem, while providing better intelligence to improve detection. The development of the detection problem was followed up more systematically by the Large Business and International line of the ATO. In adapting the ATO Compliance Model to their needs, Large Business introduced a sophisticated risk management component (Australian Taxation Office, 2000).

The core of the ATO Compliance Model, as developed by the Cash Economy Task Force, is presented diagrammatically in .

Example of regulatory practice with ATO Compliance Model

On the left hand side of the model are the motivational postures. These are the stances that taxpayers openly express in their relationships with the tax authority. These postures were identified in earlier regulatory work (Braithwaite, Braithwaite, Gibson and Makkai, 1994; Braithwaite, 1995) to describe the way in which taxpayers controlled the amount of social distance they placed between themselves and the tax office. When taxpayers were open to admitting wrongdoing, correcting their mistakes, and getting on with meeting the law's expectations, they were likely to be displaying the postures of commitment or capitulation (see for a more detailed description of the postures). The tax official's task is relatively straightforward in such circumstances. Their authority will be taken seriously, and compliance will follow as long as taxpayers know what they are supposed to do, are treated in a procedurally just manner, and are conscious of the fact that there will be follow through by the tax authority if they do not comply.