Copyright 2017 by Andrew Gifford

All rights reserved.

No part of this book may be reproduced, or stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without express permission of the publisher or author.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Pending

ISBN: 9781939650795

Published by SFWP

369 Montezuma Ave. #350

Santa Fe, NM 87501

(505) 428-9045

sfwp.com

Find the author at andrewgifford.com

TABLE OF CONTENTS

To Jim and Heather, who taught me about family

To Rose and Jimmy, who taught me about faith

To Genie, who taught me about love

And to Alan, who tried to teach me about patience

A NOTE ON NAMES, PLACES, AND ICE CREAM

For reasons of privacy, I have changed the namesand, in certain cases, locales or other identifying detailsof some of the individuals, companies, and organizations within these pages. These changes include all of the people at my college and at my places of employment.

In addition, Ive occasionally condensed or simplified timelines for the sake of narrative flow. This is especially true in the sections that detail my childhood and those that take place throughout the 1990s.

The Giffords base mix recipe and technique detailed herein have been cobbled together from the remembrances of multiple employees, contract workers, and my maternal grandfather. If readers wish to re-create the ice cream, its important to remember the larger context of the recipes history, as revealed in this narrative. Most likely, very few of the people with whom I spoke actually made the mix themselves. Proceed at your own risk.

PRELUDE

AT THE LAKE, 1979

We were ice cream people.

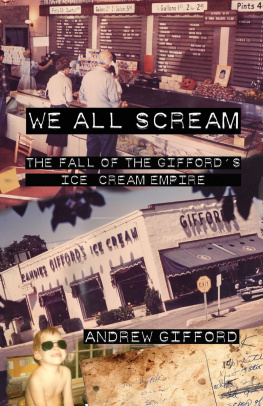

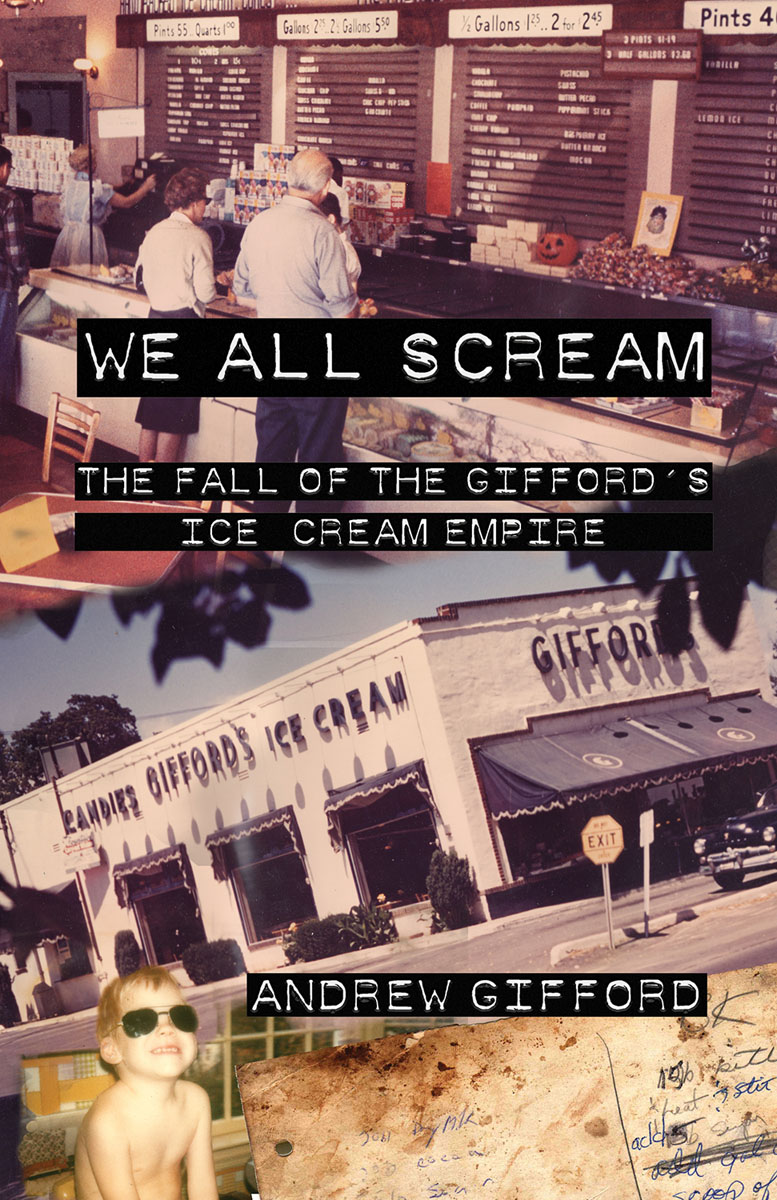

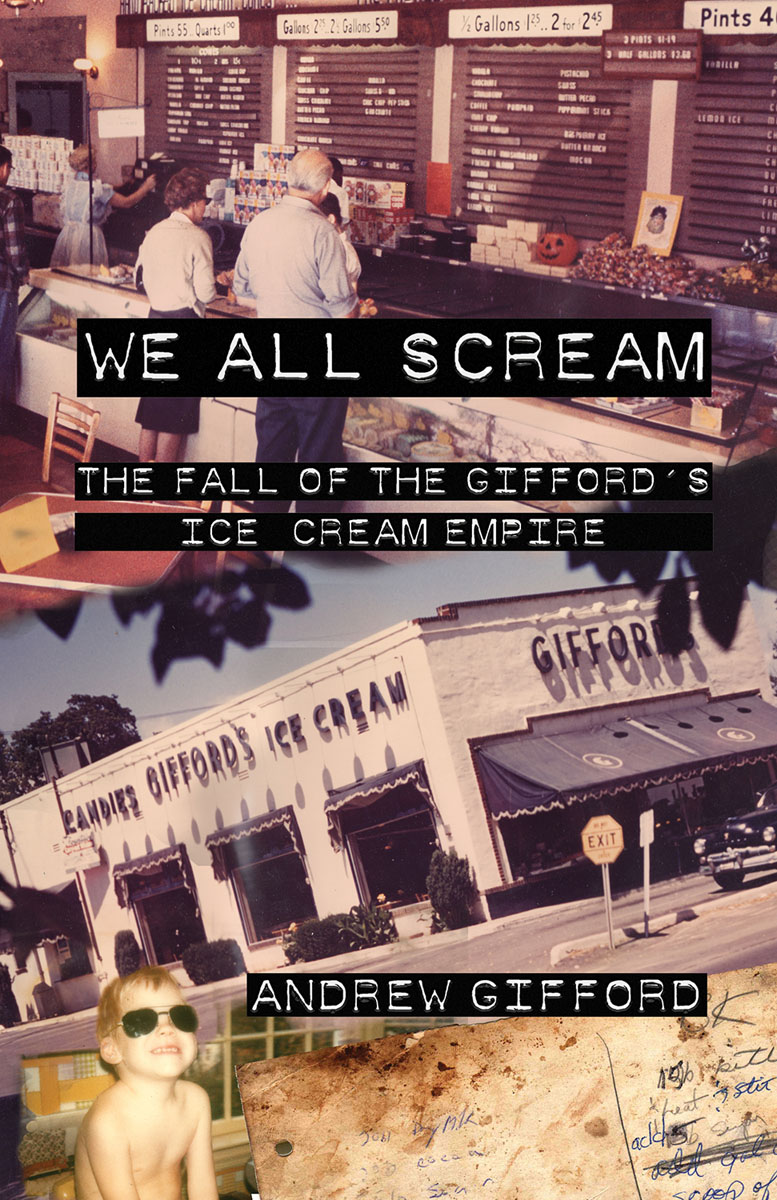

We ran a multi-million-dollar empire that had thrived since 1938. For generations of Washingtonians, our name was on the tip of the tongue when they thought of ice cream and candy. Presidents lined up for a scoop next to office workers and laborers. At the scarred wooden tables in the various Giffords parlors around the DC area, lovers held hands and children celebrated their birthdays, year after year. Come opening time, there was almost always a line at the door. On more than one occasion, when a first-shift worker failed to show and the store didnt open on time, small mobs broke in and served themselves. Almost everyone left payment on the counter.

In the Giffords parlor, watching a waitress balance a tray of sundaes as she approached your table, everything must have seemed perfect. Beautiful, even. Maybe I seemed perfect, too, that boy under his mothers wing as she swanned past the tables toward the back of the store. What a dream to be the prince of ice cream!

Except it wasnt.

In 1979, I was fivetoo young to understand much about our family business, let alone what was about to happen to it and to us. Today, Im still not sure I understand.

Giffords Ice Cream and Candy Company was founded by my grandfather, John Nash Gifford. He died in 1976, leaving the business in turmoil. His wife, my grandmother Mary Frances, lay dying in a hospital bed. My father, Robert Nash Gifford, struggled for control of the empire against both his fathers last surviving partner and my maternal grandfather, Allen Currey, who maneuvered to take over in my name. In the chaos, my mother, Barbara, signed on with my dad in an elaborate plan to siphon off profits and plunder the payroll and pension accounts.

As a child, I knew none of this. My paternal grandparents were strangers to metheir history hidden, muddled, erased. From my parents I learned only that I was an accident, easily ignored. What little I thought I knew about my family was a lie, and it would take me over three decades to figure that out. The fact was, long before the public end of Giffords Ice Cream, my father had decided to kill it.

This is a story about what was lost. Its a story about the dead. Its a story about me. It begins at a lake in western Maryland.

My earliest memory.

The water in Deep Creek Lake was dark, calm, and chilly, even under the harshest summer sun. My mother called it mountain water with a strange, spooky reverence in her voice. Water without a bottom, she said. Deep Creek Lake, though tamed by man, seemed primordial. There were a few man-made beaches, maintained by the Wisp or Alpine Village, the two major resort hotels, but most of the shoreline was comprised of drowned trees, rocks, and sticky black mud.

As we approached in our Caprice station wagon, we passed a turnoff just before the Wisp that led to an abandoned quarry. Three great caves had been blasted through the side of the mountain, and ruined chain-link fences had been thrown up as ineffectual barriers. Around these gaping maws, rusting equipment lay forgotten. Slippery humps of rocks made dangerous trails back into the darkness, each surrounded by oily black water.

Mom was a rockhound. The first thing we did after we checked into our hotel, instead of going to the lake, was to cross the road and climb to the quarry site. On our trip in 1979, new fences had been installed to block access to the caves. But Mom had anticipated this and carried along a set of bolt cutters. She made a hole in one of the fences, grabbed my hand, and led me through, producing a cheap flashlight that cast a weak beam as we slowly moved into the caves.

A cold breeze blew from within the heart of the mountain. A barely audible hum, punctuated by sounds of dripping water and skittering rocks, summoned mental visions of ghosts and monsters. Mom stopped to chip rocks out of the walls while I nervously watched the crumbling ceiling. Occasionally she would shout in triumph and bend down to show me the fossils shed been extractingstrange, ancient creatures trapped in stone. I carefully touched the outlines of their bodies, and Mom told me that, one day, we would become fossils, too.

Eventually, we went far enough for the daylight behind us to grow distant and then vanish, leaving us alone with the flickering beam of Moms flashlight. In that darkness, she shouted: I am here! I have come!

I feared that this might be a summons and waited nervously for a response. I looked up at her, her face hidden in shadow. She stood unflinching, waiting.

I have brought Andrew! she added.

Her hand, hard on my shoulder, kept me pinned at her side. After a few tense, quiet moments, we turned and left. She seemed disappointed. I asked what was wrong as we emerged back into the warm summer day. She shook her head, now sullen and distant, and pushed me along the dirt road. She didnt speak for the rest of the evening.

First thing every morning for the entire vacationfor every vacation at Deep Creek, year after year, rain or shinemy parents would rouse me and we would go out on the lake in a rented boat and motor around without any sort of goal in mind. We spent entire days motoring the lake like this, my father making endless circuits of the erratic shoreline, pausing to float near the most desolate stretches, where the water disappeared behind the gnarled branches of sunken trees.

Between the two of them, they would empty a cooler of beer and bourbon. Mom would take each can out and tap the top with her fingers before cracking it open with a sigh. When the gas got low, Dad would pull into a dock and refuel, and then wed start off again. As we drifted aimlessly, my father sat in the captains chair, staring ahead, while my mother turned the number of flattened beer cans into a math quiz.

Next page