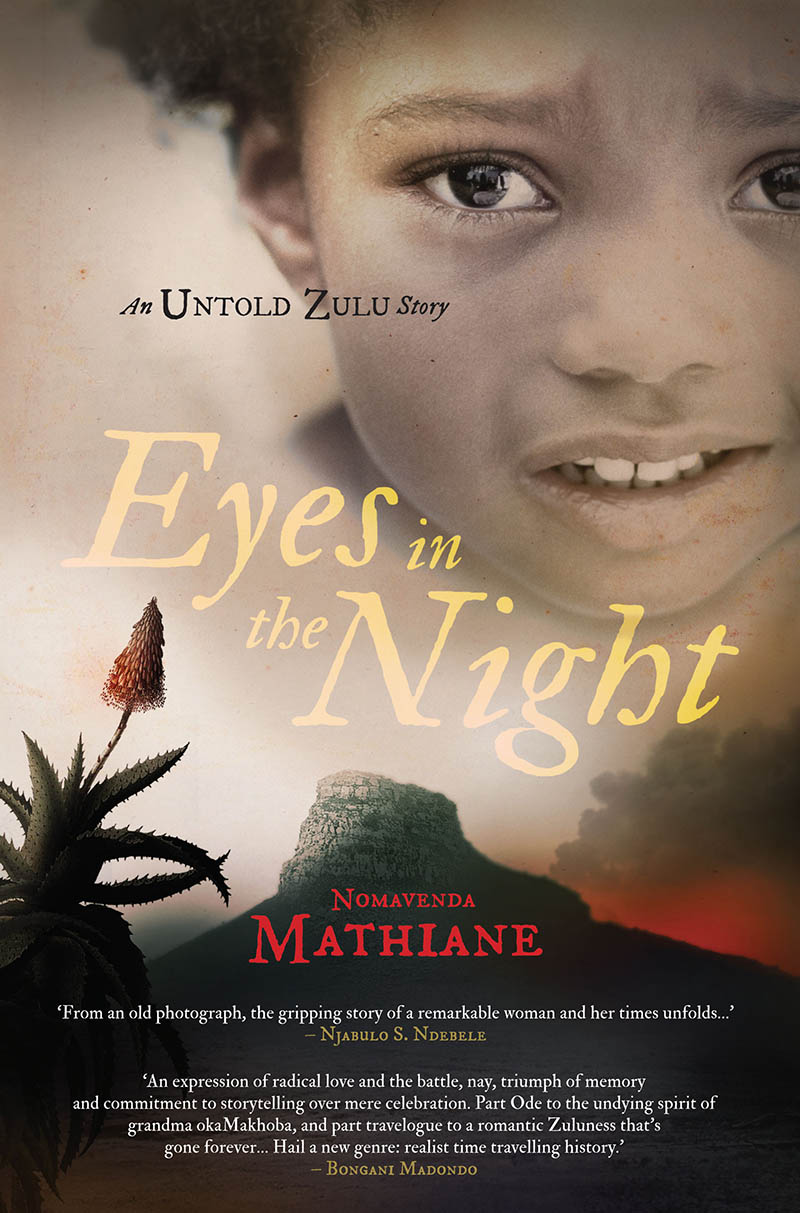

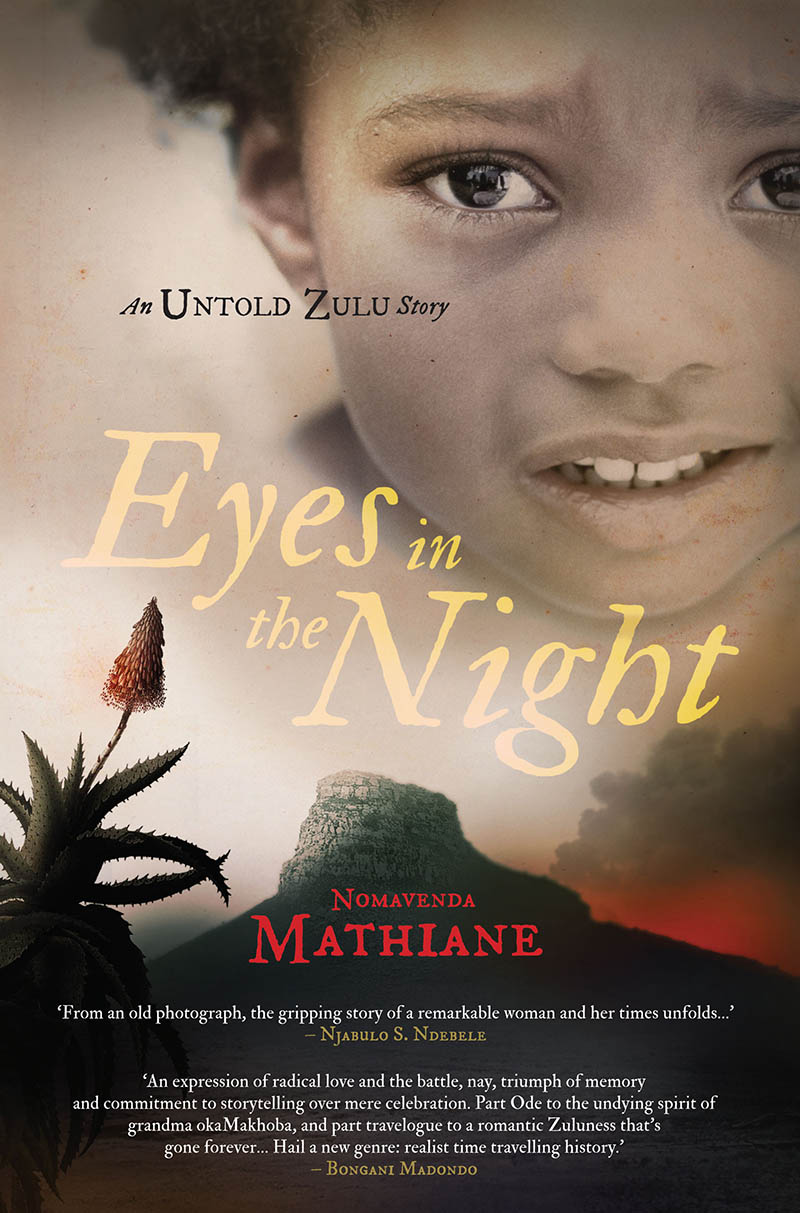

Eyes in the Night

An Untold Zulu Story

Nomavenda Mathiane

Authors note: Recording oral history is full of challenges, particularly with regard to the accuracy of historical fact. I have tried to reconcile the oral stories with the dates, names and places in formal historical accounts but some inconsistencies have been impossible to resolve completely because the people in the story are no longer around to verify their memories. I hope this doesnt detract from your reading.

Nomavenda Mathiane, 2016

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage or retrieval system, without permission from the copyright holder.

ISBN : 978-1-928257-24-0

e- ISBN : 978-1-928257-25-7

Published by Bookstorm (Pty) Ltd

PO Box 4532

Northcliff 2115

Johannesburg

South Africa

www.bookstorm.co.za

Edited by Pam Thornley

Proofread by Kelly Norwood-Young

Cover design by publicide

Cover image by Gallo Images

Book design and typesetting by Triple M Design

Ebook by Liquid Type Publishing Services

For Kings Cetshwayo and Dinuzulu, who fought gallantly in defence of the Kingdom

Contents

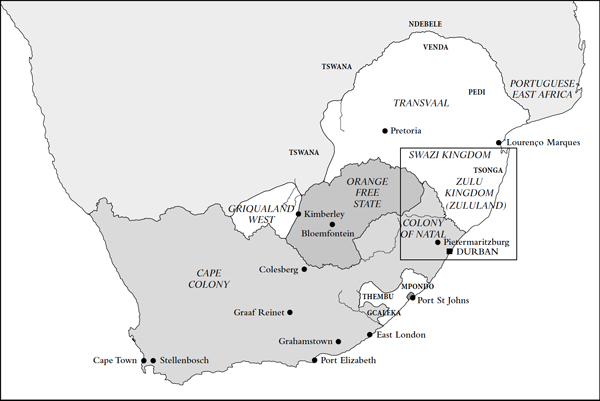

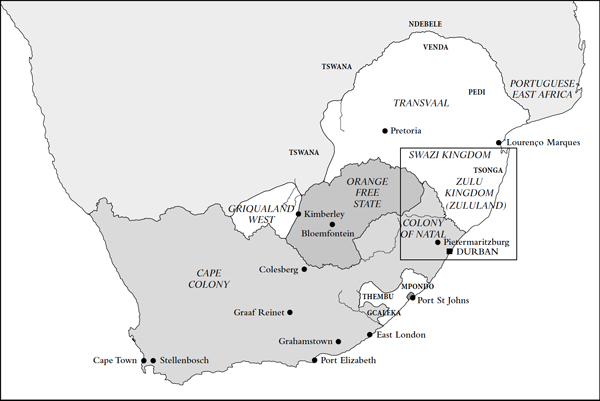

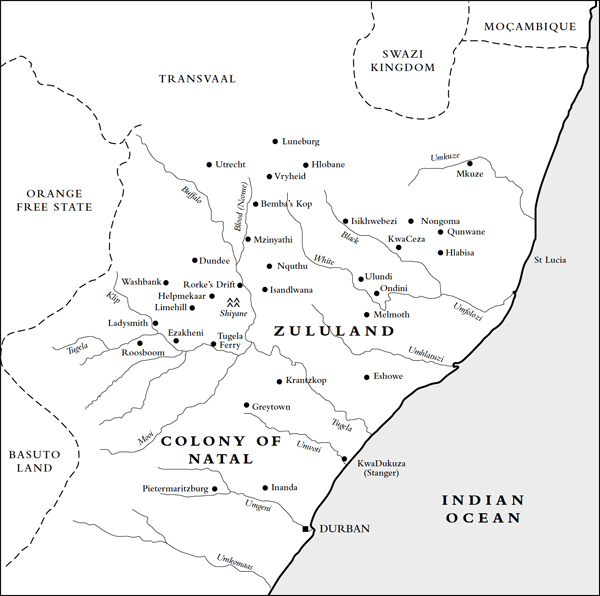

Map of southern Africa, circa 1879

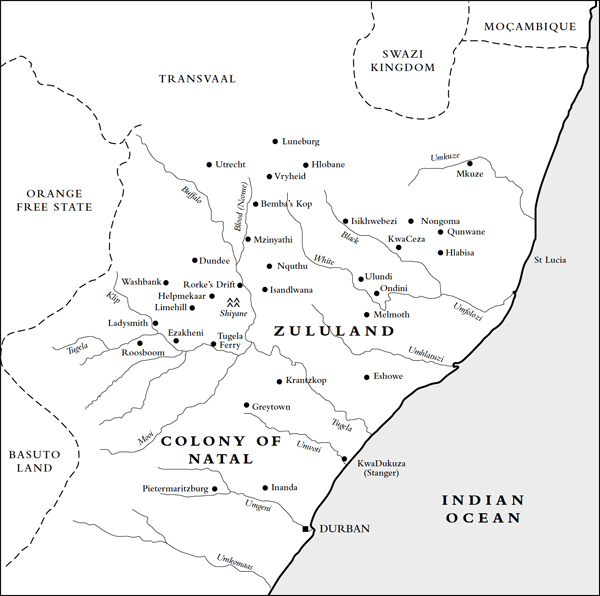

Map of Zululand

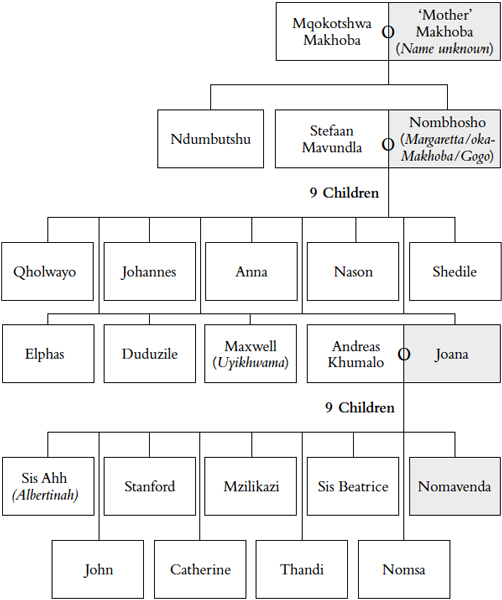

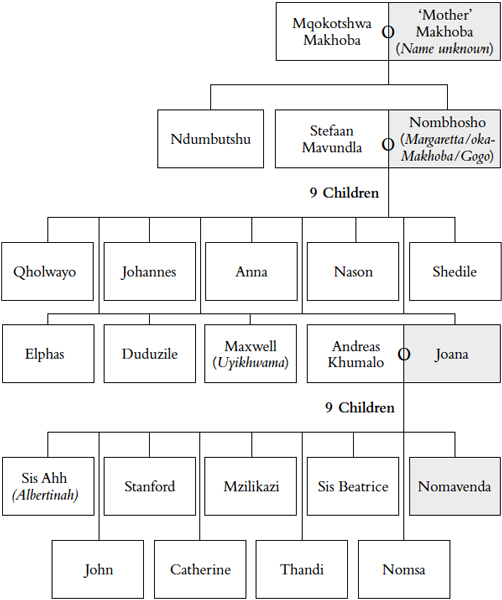

Matrilineal Family Tree of the Makhoba Clan

O = Marriage

Prologue

Six months before my mother died, she gave me her mothers reference book and asked me to get professionals to reconstruct the photograph in the book. She pleaded with me to take good care of it because it was the only photograph she had of her mother. I thought it odd that she should entrust me with the task because she usually assigned important duties to Mzilikazi, my older brother. I took the book from her and chucked it in one of the boxes where I keep important documents and soon forgot all about it.

My mother died in July 2003 in Qunwane, an old rural settlement in the district of Hlabisa in KwaZulu-Natal. Qunwane is a village, like many in that region, populated by people who are steeped in their traditional culture and ways; where generation after generation has been led by the Hlabisa clan and has lived in harmony for years; where a death in one family is mourned by the entire community. One of the traditions strictly observed by this community dictates that as soon as it is known that a member of the community has died, men, women and youngsters busy in their fields will stop work immediately. They will be seen on the road heading back home, carrying their hoes, picks and scythes. Nobody will work in the fields until the deceased has been buried. This practice is to honour the departed and show respect for the ground where the body is to be laid to rest.

The Sunday after Mothers funeral, when neighbours and acquaintances had left our homestead, the only people who had stayed behind apart from us, her children, were close relatives. They were there to help us with the cleaning of her house and to sort out her personal belongings.

It was a warm winters day and we were lazing around eating the food left over from the funeral as well as conducting a post-mortem of the funeral proceedings. My brothers and sisters there are nine of us, six girls and three boys were sitting in my mothers dining room talking about what the speakers at the funeral had said about her. Some of the stories were hilarious while others were downright embarrassing. One speaker told the mourners that Mother boasted about her children and the way they looked after her, that she would say she was not a chimpanzee sitting under a tree wailing. She would tell locals that she had so much money that if she laid the notes on the ground she could walk on them from her house to Nongoma, which is a stretch of about thirty kilometres. Another speaker agreed with the previous speaker, saying she had once casually asked Mother where her son Mzilikazi was teaching and her answer had been: Oh, that one is tired of teaching black children. He is now teaching white kids at the university. I mean, how politically incorrect could one be? These were some of the stories with which people at her funeral service had regaled the mourners. Mother was a colourful person, full of love, song and jokes. She was ninety-seven when she died and her send-off was more of a celebration of her life than a funeral.

I was sitting next to my oldest sister Ahh this Sunday morning. Ahh is short for Albertinah. She is my mothers first-born child. Of all my mothers children, Sis Ahh is extremely laid back, soft spoken and one of the most gentle people I have ever known.

I turned to her and said: There is something Ive never understood about Sister J. (We called our mother Sister J, her name being Joana.) Do you know why she rarely spoke about her mother? For someone who used to entertain us with stories of OkaBhudu (our paternal granny, her mother-in-law), there was very little she shared with us about her mom. Do you know why?

I dont know whether or not I expected an answer. I was partly talking to myself and I was also half listening to the conversation that was taking place around the table.

Its because her mothers story was filled with too much drama, regret, guilt and, finally, triumph. That is why she did not speak about her mom, answered Sis Ahh.

Getting a reply from Sis Ahh surprised me. Her answer came out glibly and matter-of-factly. I paid little attention to it. And yet somehow it lingered in my mind.

The next day I drove her home and on the way I asked her what she had meant by saying our grannys story was sad and filled with drama. When we arrived at her house, she brewed a pot of tea and began her narrative. As she spoke, my mind vacillated from one emotion to the next, from sadness to anger; from a feeling of helplessness to disbelief. When she had finished talking about Grandmothers incredible tale of woe and triumph, I was filled with an overwhelming sense of pride. I was proud of the fact that I came from such ancestry.

Albertinah knew our grandmothers story because when my parents, who were officers in the Salvation Army church, were sent to do missionary work in Venda they could not take her with them because the move, which took place mid-year, would have interfered with her schooling.

They left her with Grandmother. Sis Ahh was practically raised by her. I think Ahh was ideally suited to be the one entrusted with the information. She has a calm personality and is blessed with an excellent memory. In her quiet and soft manner of speaking she recalled incidents and events that took place many years ago and related them as though they had happened yesterday. She is a retired nurse and her last post was at the local hospital in Hlabisa, a facility that has become internationally renowned because of the role it has played in treating patients who are suffering from HIV and AIDS. Having trained and worked in many parts of that region she knows and understands the lie of the land and the practices of the area like no other person I know.

Next page