To Mum, Dad and Alice

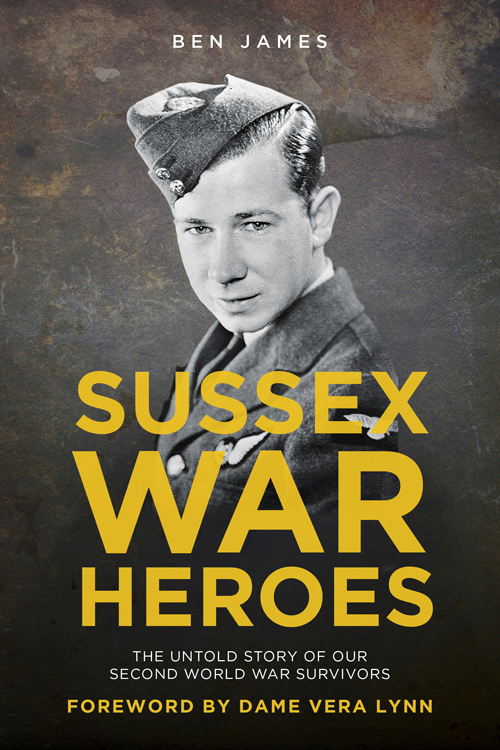

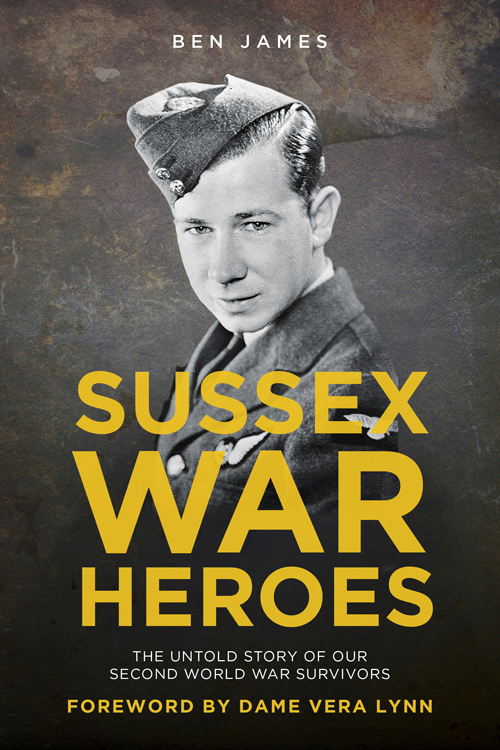

I would like to thank a number of people for their help with making this book happen. Firstly, The History Press for agreeing to publish it and in particular Nicola Guy, Ruth Boyes and Emily Locke. For allowing me to use their photographs, I am extremely grateful to those at The Argus .

Special mention must go to Dame Vera Lynn for agreeing to write a foreword and her daughter Virginia for arranging it all.

Most importantly of all, thanks goes to the survivors who allowed me into their homes and offered me coffee, tea, biscuits and even whiskey. They put up with me pestering them for hours on end, asking dozens of questions about something that happened more than seventy years ago.

Some of the subjects we covered were not easy to talk about and I no doubt caused some distress by bringing up these matters. However, those I spoke to were nothing but hospitable, helpful and so incredibly modest.

I would like to thank my mother, Jane, and father, Phillip, who instilled in me an interest and passion for history and in particular for the Second World War. Finally, my partner Alice, without whom this would not have been possible. Her advice and guidance resulted in the book you are holding.

CONTENTS

DAME VERA LYNN

I n the winter of 1940, at the height of the Blitz, I was still performing in Londons theatres. In the West End there were air-raid shelters, sand bags outside buildings, and windows were taped to stop them from shattering. But other than that, it was a city unchanged.

The bombs fell each night, but the people of London were not going to let that stop them, they wanted to carry on as usual. People went to work, the buses ran and the restaurants and hotels remained open. There was no hysteria and no panic.

Entertainment was seen as key, with the morale of the British people vital to the war effort. So it was a busy time for me and I was in demand not only for live performances, but for radio appearances and the like. But I knew that what I was doing was important, it was more than just singing.

I was living in Barking at the time and would travel into the West End each day in my little Austin 10. I loved that car but it did have a canvas top so I would always have my tin helmet on the passenger seat just in case the air-raid sirens went.

I would park up outside the Palladium or Adelphi or wherever I was that night you could park anywhere in London in those days and I went to get some dinner before I would go on stage and sing. By the time I had finished the Germans would often be on their way over and I would have to make a decision. It was quite a journey home, which took me through what was known as Bomb Alley a part of the East End regularly targeted by the Germans. So I had a rule: if I had gone through Aldgate by the time the sirens went, then I would continue home, with my tin helmet on. If I hadnt reached Aldgate, then I would turn back and return to the theatre and spend the night there. Behind the stage door there was a big thick wall, where they kept the scenery and props. I would sit behind that and I would listen to the bombing outside with the theatre nightwatchman for company.

Each morning London would wake; the people would assess the damage and get on with life. There was no question of giving in; we knew we had to get through it. I have always thought of that resilience, that strength and that fighting spirit as something unique to the British. My generation had that special something in abundance, but I would like to think that if something like that happened again, the current generation would be the same.

The spirit I witnessed during the darkest days of the Blitz in London is the same that got our brave boys through their darkest days fighting in Europe, Africa and the Far East. Without this strength of mind and character I am not sure we would have made it through.

Like everyone else during the war, I wanted to do my bit. Everyone had their talents and mine happened to be singing. I had been on the stage since the age of 7 and I was well known by September 1939. But I knew I was not just singing for singings sake any more, I knew it was more important than that.

In 1941 I began recording a regular show for the BBC called Sincerely Yours and I would travel to the recording studios in Maida Vale and Piccadilly. I would sing, respond to requests from servicemen and do whatever I could for the war effort. At the time I was also receiving thousands of letters from around the world from British servicemen. They were asking for me to reply, send messages to their loved ones and give dedications on the radio. I realised how much these men must have been missing home and I made sure I replied to each and every one. With the help of my mother and another girl, who we got to help with the workload, we typed responses to all of them and had hundreds of photos of myself printed to send out.

I knew how important it was, some of these men had been away from home for four, five, six years, and just to hear from someone they could relate to meant so much to them.

But I wanted to do more, especially for those who were fighting thousands of miles from home. I had read in the newspapers about the boys fighting out in the heat in Burma and so I decided I would go there. I asked ENSA (Entertainments National Service Association) if they could arrange it for me, but they initially said no because it was too dangerous. I somehow managed to persuade them and after being made an honorary colonel I was not allowed to go out there as a civilian I packed my bags and set off with my pianist.

First we stopped off in Egypt, before visiting more troops in India, and then finally we reached our journeys end, Burma. It was hot, humid and the conditions were basic to say the least. But it was worth it to see the reaction of the boys out there. Some of them had not seen a woman for four or five years. Their spirits were lifted and I truly knew then the importance of what I was doing. They had been through a terrible time and many of their friends had died. The English countryside must have felt like a world away to them and there was no guarantee of when they would return.

As I was leaving, a young soldier said to me, Now you are here, home doesnt seem so far away. That meant a lot and I have never forgotten it.

They were all so brave and just so grateful that I had come out to see them. They would ask about home and how we were getting on and what we were eating and simple things like that. But the sad reality was that many of them would never see home, their loved ones and families again.

In the years since I have met hundreds, if not thousands of veterans at events and commemorations. Like those in this book, they all share that incredible fighting spirit, courage and humility. They never make a big deal of what they did for this country during the war, but the fact is, if it were not for them, the world could be a very different place today.

I was a young woman at the time, but it is a period of my life I will never forget. I often think back to my experiences in Burma as it has a special place in my heart. I have always tried to help out where I can in the years since and I was awarded the Burma Star medal in 1985. I attended and performed at the Burma reunion for fifty years at the Albert Hall and they were fantastic events to be part of. The audience would be full of veterans and together we would remember the brave boys who didnt make it home. But as each year passed, I noticed a change. With each concert there would be fewer and fewer veterans and more family members taking their place. With most of the veterans of the Second World War now well into their nineties, it will not be long until they are all gone. That is why books such as this are more important than ever. We must record their stories before they are lost. We must remember them.

Next page