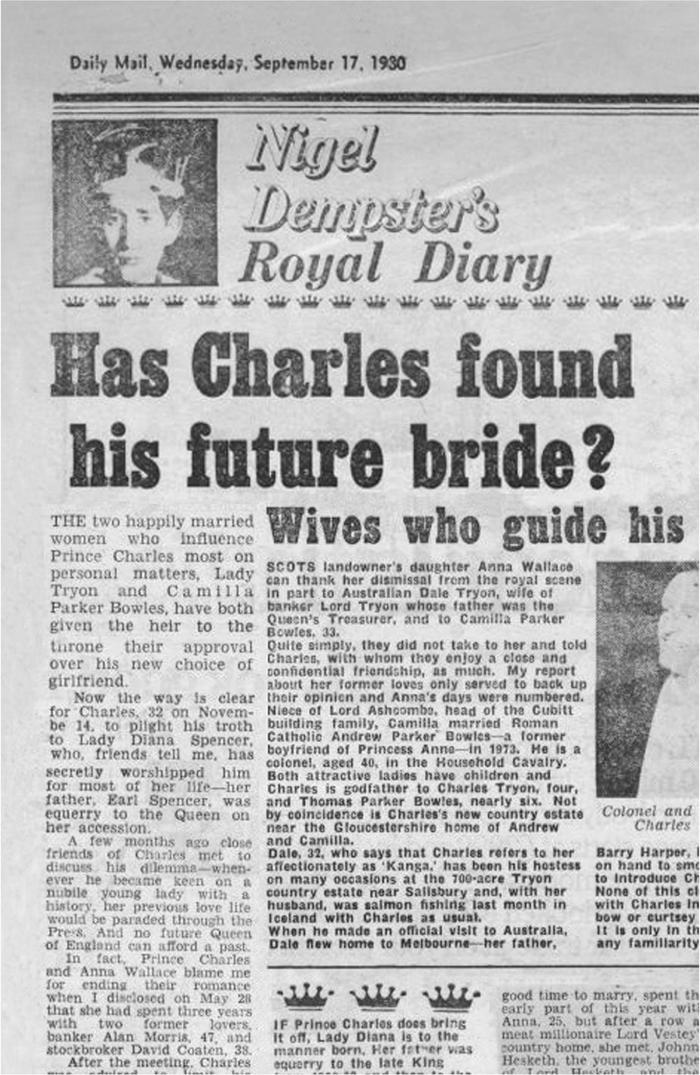

F uture generations may wonder how, in less than 50 years, Britains generally tame press transformed itself into a celebrity circus where reality TV stars held the front pages with the details of their sex lives. What caused such changes in the media, its audience and subjects? To some extent, the answer is Nigel Dempster (19412007).

The life and works of the late gossip columnist inform and entertain at so many levels. His wine-soaked journey through old Fleet Street and Society is a tragi-comic romp. His chronicles of the upper classes afford a wealth of opportunities to devour and condemn the follies of an extinct species. And when these themes are set against a history of the media over Dempsters lifetime, we can see how and why society with a small s has been so transformed and how and why he flourished. As he would say when on his high horse, social trends are as important to history as economic and political ones. The devil is in the detail.

For a quarter of the 20th century, Dempster was the man perfectly placed and qualified to record and accelerate the end of the age of deference, the transfer of wealth from the aristocrats to plutocrats, and the collapse of standards in the old Establishment. The highest paid journalist in Britain, as much a brand as a person, he was a vital resource at the Daily Mail. It is, then, an irony that the genre to which he contributed so much eventually left him behind. However, the sphere in which he succeeded was created in the shadow of the Sun, and one day his brand of journalism would be eclipsed.

In the Nineties, he often used to say as much to me: The stories that should be in my column are now frontpage news. And its true that, to profit and survive, the British press had become less about public interest than the publics interest. But Dempsters value had also declined. Long before his enforced retirement, supermodels and footballers were shoving aside his roster of ragged gentry and ageing jet-setters; and the competition from gossip magazines was ever fiercer. Then again, it may be that he was simply a by-product and a casualty of broadcasting.

I defy anyone to make an absolute distinction between gossip and news or the means of gathering them. But it is clear that, as the public began to take its information from the airwaves, the printed press became more a medium of entertainment, in a process that is still continuing. Like some ageing leading lady, Dempster may simply have served his purpose.

I first encountered him in 1986, when I rang for a quote to insert into a piece that I was writing. The next year, when I was in the Mail offices off Fleet Street, I saw him across the desks, striding to his corner room, while shouting, I own this place, I own this place! If it wasnt for me youd all be in the gutter and in 1990, we became better acquainted at the Sunday Times, where I ghost-wrote a feature for him. (Dempster had somehow wangled a commission to puff one of his books with no seeming intention of fulfilling it.)

Though I cant say we were close, we got on well enough for him to come for supper at home, where he regaled us with ungallant tales about a former conquest who was also great friends with another guest. (She was a fluffy little thing fine down all over her.) He was the last to leave and when I was briefly out of the room, he came on pretty strong to my then-wife. Luckily, she was more amused than shocked and so, Im afraid, was I for Dempster was one of those characters who could get away with almost anything because they made you laugh. I seem to recall he pinched my bottom on the way out.

He was a camp figure, with a signet ring on his pinky, wearing too-tight suits from which as the EveningStandards editor Geordie Greig puts it, his arse protruded like an apple. But at the top of his game, such was his power and influence that two kings Hussein of Jordan and Constantine of Greece were once seen queuing up to greet him in Harrys Bar. At the Mail, it is remembered that when the last proprietor needed distraction or his wife attention, Dempster would be wheeled out to entertain them. He was family, they say. Vere [the 3rd Viscount Rothermere] and Bubbles loved him. But so did the less exalted. Good on yer, Nigel, the travellers at the Epsom Derby would shout when he arrived in Lord Whites helicopter. He was renowned for the lavish Christmas boxes he gave to the lads who liveried his horses.

My Purple Prose, Chatty Corner and Superfluous, Aardwolf, Switch and Pretoria Dancer, Rhyming Prose and General Gossip; over the years, Dempsters readers would get to know all these beasts through his columns and many characters from the track. Investing huge amounts of time and money in racing and gambling, he was a different man if as much himself in this other life, and I can only apologise to the turf fraternity if my allotted sum of words is not adequate to do it justice.

I must apologise, too, to some of the victims of Dempsters vicious temper. Most of those on the receiving end particularly his staff came to see it as the flipside of his generosity, but a minority may feel that, while I have touched on a couple of notorious incidents, they hardly give a taste of his tyranny. I hope the aggrieved will understand that I have given some regard to his medical condition.

True, he had a foul mouth and was quite capable of manhandling his assistants, long before he had any excuse except a sore head from drink. In his later career, he spent hours every day firing off memos to people sitting only feet away from him. He once threatened a female member of his staff with dismissal for conceiving, and sent her a note saying How dare you get pregnant?. But the horrible illness that led to his death at 65 progressive supranuclear palsy can incubate for up to fifteen years, manifesting itself slowly at first, before suddenly accelerating. Its symptoms include paranoid delusions and violent mood swings. Although it was only diagnosed three or four years before his death, it may have been with him for half his working life.

Another thing. To some, the rehearsal of Dempsters greatest stories will seem old news. I can only reply that to most readers even other journalists they are now ancient history, and need to be re-told. I am more troubled that I could only include a fraction of the tens of thousands of items that appeared under Dempsters name. Nor could I mention or interview every significant friend, colleague, contact and enemy. They were myriad, as one would expect of the worlds greatest gossip columnist and from most he earned some kind of respect. Take the playwright Tom Stoppard, who cant have relished having his love life plastered all over the papers. When I mentioned to him that I was writing this book, he was surprisingly generous. Dempster wrote some pretty unpleasant things, said Stoppard. But unlike most of his kind, he was generally accurate. And when one met him, at least he told the truth.

Still, I come not to praise Dempster; he was virtuous neither in public nor private. He did a job that you may condone or condemn according to your lights. But he was a phenomenon, of a type now disappeared. And through his eyes we can view the world long swept away that he broached, moved in and reported on. Here, titles commanded respect, and white tie was worn at balls where bands played dance tunes to which teenage couples knew the steps. The indiscretions of the Royal Family could not be noised abroad without damaging national stability. Drinking and driving was more a challenge than a crime. And the lower orders were kept behind the green baize door until Dempster threw it open.