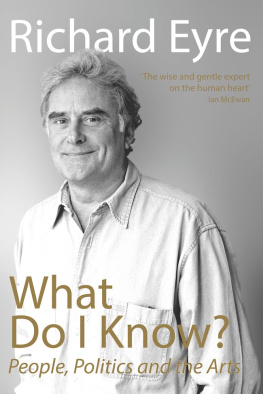

Richard Eyre

WHAT DO I KNOW?

People, Politics and the Arts

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

Contents

To

my granddaughters

Eva and Beatrix

We are, I know not how, double in ourselves,

so that what we believe we disbelieve,

and cannot rid ourselves of what we condemn.

Montaigne

Introduction

What do I know?Que sais-je?is the question that Montaigne asks himself in one of his essays. Its a sound reminder of sceptical faithif that isnt an almost-oxymoron. Its written in Latin, along with many other aphorisms and epigrams from Greek and Roman philosophers, on one of the roof beams in his library at the top of his famous tower.

I visited Montaignes tower with my sister, who lived nearby in the Dordogne, a few weeks before her death last year. She had little in common with her neighbour: where Montaigne would think out loud in his writing and equivocate in his politics, she preferred the headbutt. She was a contrarian who loved an argument even though she would never concede defeat. My father (a difficult man himself) used to say that she went through life like a flame-thrower. She burned with a bright flame, and the flame could sometimes scorch you, but the flame illuminated the lives of everyone she came in contact with.

Montaigne had been provoked into starting to write his essays by the death of a great friend and it was his words that came to mind when my sister died: If you press me to say why I loved him, I can say no more than because it was he, because it was I. So it was with my sister.

If I have anything in common with Montaigne it is that I write to discover what I think. Unlike Montaigne, who wrote obsessivelylike a blogger before the eventI wrote because I was asked to do so. Those who asked me to write most of these pieces were Annalena McAfee, Claire Armistead and Lisa Allardice of the Guardian, Sarah Sands of the Telegraph and later the Evening Standard, Emma Gosnell of the Sunday Telegraph, James Inverne of Gramophone, and Richard Lambert of the Financial Times.

The remainder of the pieces in this book were talks or lectures or eulogies. I would never have become a writer of any sort if it had not been for the publisher, Liz Calder; I would never have continued to write had it not been for my wife, Sue Birtwistle.

People

John Mortimer

John died in 2009. I was asked by his family to give the eulogy at his funeral in the parish church in Turville Heath, where hed been born and lived for eighty-five years.

It was said by another national treasure, Alan Bennett, that Philip Larkins waking nightmare was of thousands of schoolchildren massed in the Albert Hall chanting in unison: They fuck you up your mum and dad. Alans gloss on this was that, if your parents didnt fuck you up and you wanted to become a writer, then theyd have fucked you up good and proper.

The formula worked in Johns case: his father diverted him from being a writer to becoming a barrister and unintentionally left him a great legacy: the law became his subject. The other indispensable legacya paradoxical onewas that while his father passed on a love of poetry, he withheld his own love. John didnt mimic this deficiency: in all his memoirs he showed an undiminished love of his fatherand of his own childrenand its a remarkable homage to his father that John went out of the world in the same house that he was brought up in.

As a lawyeras in lifeJohn was unjudgemental: his sympathies were instinctively with the defendant. The only case he turned down was an assistant hangman who had committed murderthe idea of defending a man who was licensed by the state to kill criminals was beyond the limit of his tolerance. But his reputation for defending the indefensiblewhether they were murderers or alleged pornographersadded to his allure as a buccaneering renaissance man who wrote plays and novels in his time away from the Bar. For John the law was an English pageant full of tales of people who had been undone by greed, or poverty, or passion, or folly, and it was always for him underscored by a belief in justice and in liberty.

I never tired of hearing Johns anecdotes and he never tired of telling them: the woman who was giving evidence in a case in which shed been sexually harassed but was too shy to say out loud what had been said to her, so a note was passed round the court ending up with a dozing woman jury member, who was jolted awake by her male neighbour. The note read: I would like to fuck you. The judge asked the woman to hand the note to the clerk. Merely personal, my lord, said the woman and pocketed it. Then there was the camp judge who kept a Paddington Bear that sat beside him in his official car and on the bench when he was in court; and the woman who fell downstairs and sued her sons because she saw her husband in the hallway having his genitals devoured by the dogsthe sons having discovered him drunk and asleep in the hallway, had opened his flies and put a piece of liver there; and the prie-dieu in Norman St John-Stevass bathroom; and much, much more. These stories had the status of folk myths, which John would tell and retell in his melodious, feline, light-tenor voicequiet so that you had to attend carefullyperformed with an actors flair for spontaneity and timing.

When John finished a story hed laughhis laugh was more of a chortle than a chucklethen hed segue seamlessly into an observation about something like the decline of liberty and the Labour Party: Theyre awful, hed say, awful. The laugh became increasingly husky and wheezy over the years but laughter remained Johns default modea way both of putting troubles at a distance and of celebrating the fact that, as he said, Deaths finality makes life seem absurd.

I first got to know John as a more than casual acquaintance when, as an adoring father, he stood outside St Pauls School for Girls dropping off Emily at the gates as I did the same with my daughter, Lucy. I dont imagine that either teenage girl was particularly pleased at the time to be seen with their fathers, but I was hugely grateful to be able to chat to John and discover the man behind the public persona.

If you only knew John as a raffishly dapper wit in a three-piece suit with a silk handkerchief in his top pocket entertaining an array of admiring women aged from eight to eighty, you might have believed that he was a dilettante, an irresistible flaneur with a private income. The truth is, of course, that he worked enormously hardevery day of every year. On holiday with John you could never get up early enough to be up before he was at work. From sunrise he would be sitting outside under a tree with a pen and a pad of lined A4 on his lap. The house would wake hours later and John would write on until a late breakfast and an early glass of champagne, happy to hear the voices of women in the house; happier still if they were talking about him.

As a journalist he was a dogged and industrious pro. Like a barrister dutifully following the cab-rank principle, he never knowingly refused a commission. When Princess Diana died he was asked by the Daily Mailnot his natural constituencyto do a piece for them. He went to Kensington Palace and approached a mourner: Go away, she said, I dont want to talk to the paparazzi.

As a writer he didnt become adjectivalone doesnt speak of Mortimer-esque eventsbut one does speak of a Rumpole moment, and the character of RumpoleJohns alter ego who embodied the apparent oxymoron of a loveable lawyeris an enduring monument to his talent. All his workhis plays and novels as much as his journalismwere in his own distinctive voice: witty, lucid, louche and sometimes ruefully acerbicnever less than when writing about those politicians he grew to despise.