Contents

Guide

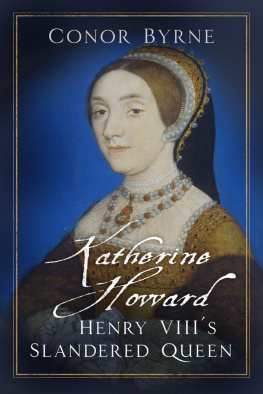

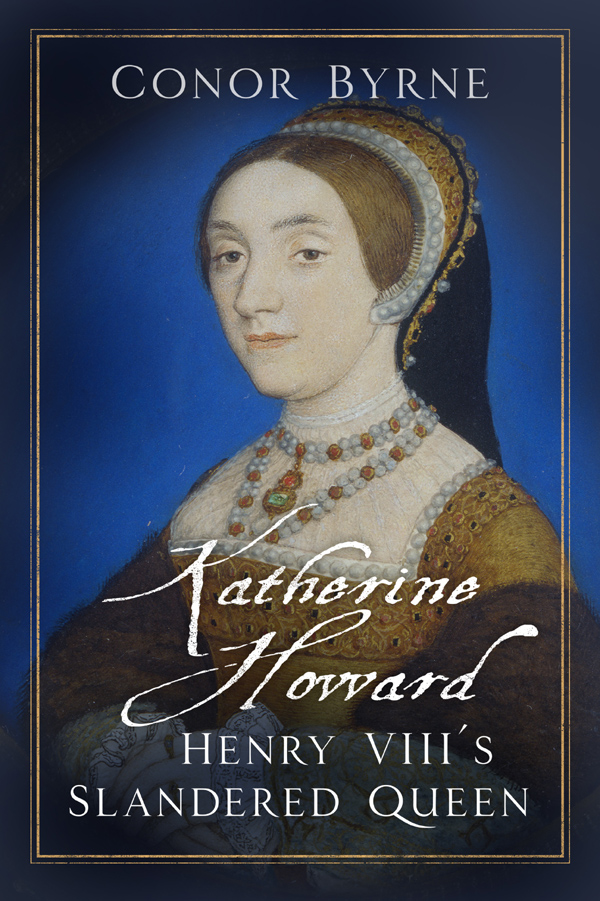

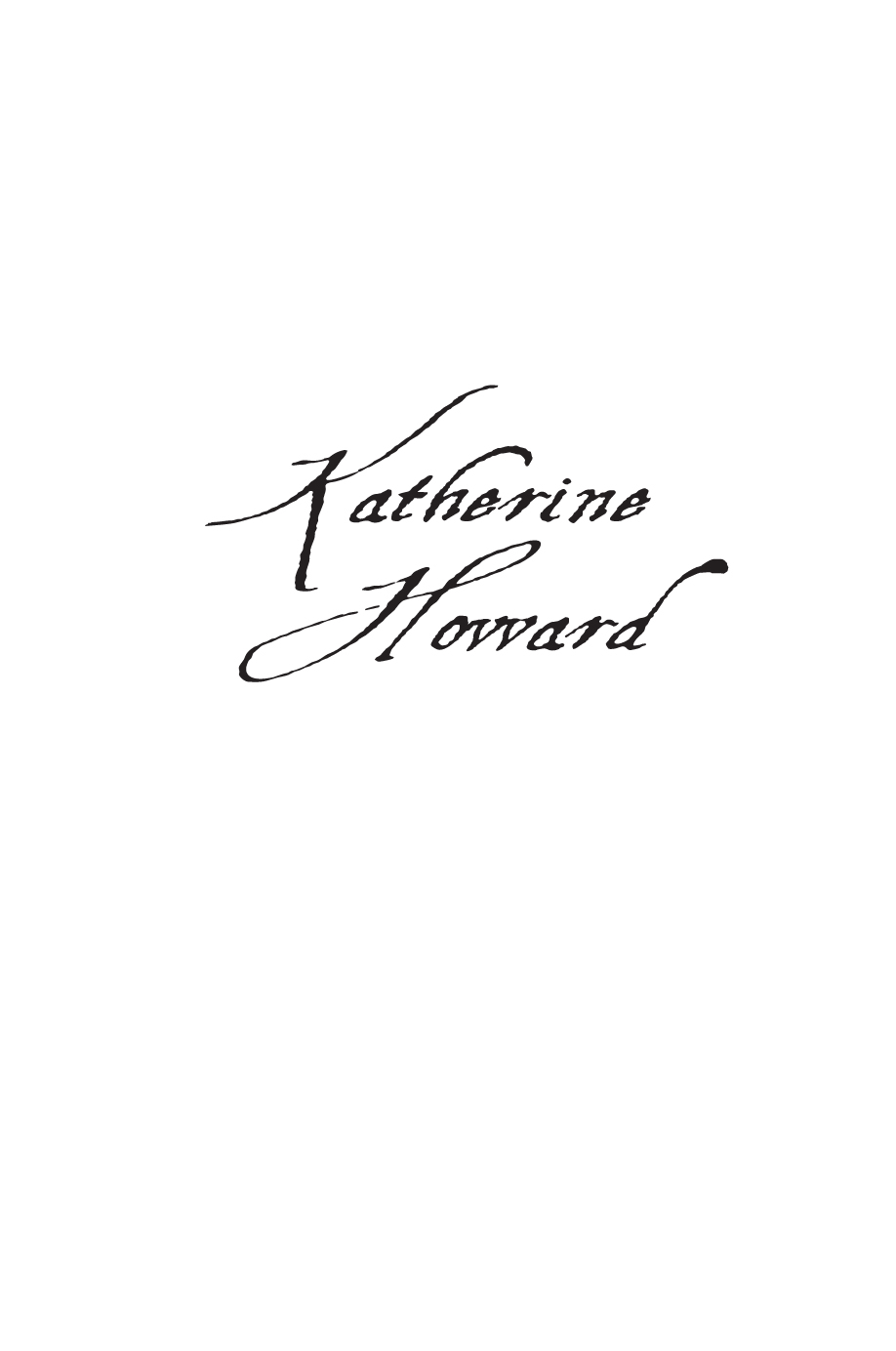

Front Cover: Portrait of a Lady, perhaps Katherine Howard (152042),

Royal Collection Trust / Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II, 2018

First published 2019

The History Press

The Mill, Brimscombe Port

Stroud, Gloucestershire, GL5 2QG www.thehistorypress.co.uk

Conor Byrne, 2019

The right of Conor Byrne to be identified as the Author of this work has been asserted in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reprinted or reproduced or utilised in any form or by any electronic, mechanical or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without the permission in writing from the Publishers.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data.

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978 0 7509 9158 2

Typesetting and origination by The History Press

Printed and bound in Great Britain by TJ International Ltd

eBook converted by Geethik Technologies

CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

THIS BOOK IS THE culmination of over five years of research into the life of one of Englands most defamed queens consort. When I began researching Katherine Howards brief life in 201213, very little had been written about her. Popular evaluations of her usually repeated sordid rumours of her sexual misdemeanours and the scandalous reasons for her execution after less than two years of marriage to Henry VIII. Katherine Howard: A New History (2014) aimed to redress these shortcomings in the extant writing about her; since then, two further biographies of Katherine have been published. Some of the theories I put forward in the 2014 biography have subsequently been adopted by other historians, including my agreement with Susan James that the portrait dated c. 154045 housed at the Metropolitan Museum of Art (reproduced in the images section of this book) may well be a likeness of Katherine painted during her brief period as queen.

This biography provides further insights into Katherines life and queenship, while responding to the latest scholarship concerning her. It stresses my initial conclusions that Katherine was neither adulterous nor a juvenile delinquent who was solely responsible for, or deserved, her execution in 1542. My interpretation draws on and is informed by early modern perceptions of sexuality, fertility and gender, while providing additional evidence for her date of birth and portraiture. The present volume also offers a discussion of how Katherine has been represented in the medium of film and television. Essentially, republishing this biography has offered me a welcome opportunity of revisiting my earlier conclusions about Katherines brief life in the context of early modern gender relations. As this book indicates, I have long been fascinated by how Katherine has been represented, both during her lifetime and posthumously, by her contemporaries and by those living in the twentieth and twenty-first centuries. This book is as much a study of Katherines historiography and how she has been represented as it is a narrative and analysis of her life.

There are a number of libraries and archives that I wish to thank: in particular the University of Exeter Library, the National Archives at Kew, the Surrey History Centre, Cheshire Record Archive and Fleet Library. I want to thank the team at The History Press, especially Mark Beynon, for agreeing to take on my project and for providing invaluable support during the research and writing of this book. A number of individuals have encouraged my research and writing over the years: in particular my sixth-form teachers, Diana Laffin and Jo Chambers, who subsequently invited me to return to speak to A-level students about my experiences. I am immensely grateful for the opportunities that they have afforded me.

I must thank the lecturers, professors and teachers at the universities I attended who inspired me with their passion and knowledge of the past, especially those who specialised in early modern history and fuelled my fascination with the period. My research into Katherine Howards tragic life began in 2012, and I am very grateful to St Hughs College, Oxford, for responding so warmly to my initial research for their essay competition. I wish also to thank those who have encouraged me to write for their websites and publications over the years, including Natalie Grueninger (On The Tudor Trail), Susan Bordo (The Creation of Anne Boleyn), Olga Hughes (Nerdalicious), Moniek (History of Royal Women), Janet Wertman (Jane the Quene) and Debra Bayani (Jasper Tudor).

I would also like to thank my colleagues at the Universities of Exeter and St Andrews for publishing my research in their undergraduate academic journals and for working with me on the respective committees, whether as a writer or co-editor. I must also pay tribute to the many historians who corresponded with me over the years, with whom I discussed theories and whose work I continue to respect and enjoy, including among others Retha Warnicke, Alison Weir, Gareth Russell and Suzannah Lipscomb. Retha Warnicke, in particular, was very helpful in sharing her thoughts and research with me about Katherine.

And finally, thanks to those historians and researchers who have provided friendship and support in varying circumstances, including Melanie V. Taylor for providing both advice and editorial assistance, but also to my close friends and family outside of history who have been there for me when I have needed it.

INTRODUCTION

THE HISTORIOGRAPHY OF QUEEN KATHERINE HOWARD

In histories that treat men as three-dimensional and complex personalities, the women shine forth in universal stereotypes: the shrew, the whore, the shy virgin, or the blessed mother.

Retha M. Warnicke, The Rise and Fall of Anne Boleyn: Family Politics at the Court of Henry VIII (Cambridge, 1989).

It is not yet said who will be Queen; but the common voice is that this King will not be long without a wife, for the great desire he has to have further issue.

French ambassador Marillac writing to Franois I of France on 13 February 1542, the day of Katherine Howards execution.

FOLLOWING HER EXECUTION ON charges of high treason in February 1542, as the second of Henry VIIIs queens to be beheaded in less than six years, Katherine Howard was consigned to history as a flirtatious and irresponsible teenager who courted disaster through her reckless behaviour and adulterous liaisons with a succession of lovers under her ageing husbands nose. Unlike Anne Boleyn or Katherine of Aragon, she has not proved to be a particularly popular subject among historians, almost certainly due to the briefness of her reign and the scarcity of wide-ranging source material. Despite this relative lack of interest, the historiography relating to Katherine is significant in offering insights into how the specific political and social context has informed interpretations of the career of Henrys fifth queen. Exploring the historiography of Henrys fifth queen is relevant, from the perspective of this biography, in indicating how problems of evidence and a lack of cultural awareness have often obscured understandings of Katherines story. To many, she remains the vain and unintelligent bad girl who deceived her doting husband firstly by concealing her pre-marital past and secondly by actually cuckolding him after their marriage. It is worth emphasising, as Holly Kizewski noted, that both detractors and defenders usually reduce Katherine to her sexuality.