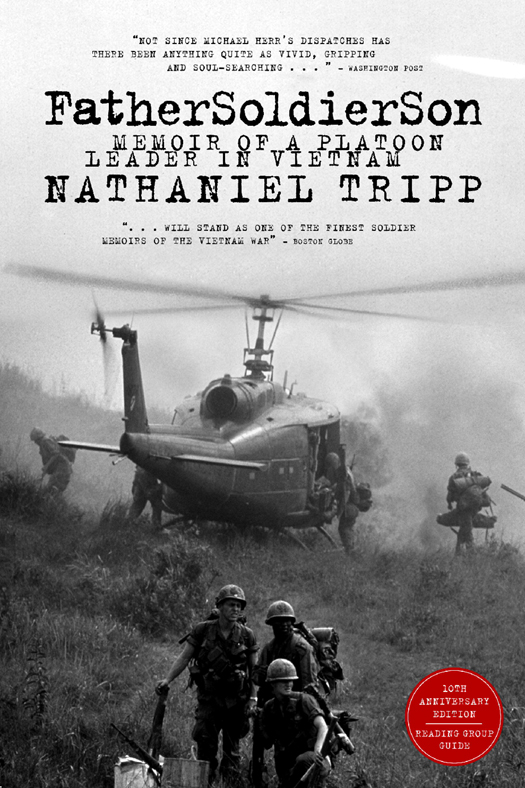

Copyright 1998, 1996 by Nathaniel Tripp

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

For information about permission to reproduce selections from this book, write to: Steerforth Press L.C., P.O. Box 70, South Royalton, Vermont 05068.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Tripp, Nathaniel, 1944

Father, soldier, son : memoir of a platoon leader in Vietnam / Nathaniel Tripp. 1st ed.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-1-58642-211-0

1. Vietnamese Conflict, 1961-1975Personal narratives, American.

2. Tripp, Nathaniel, 1944- . I. Title.

DS559.5.T74 1997

959.7043092dc21 96-46845

v3.1

To my sons: Eli, Sam, and Ben

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This book wouldnt have been possible without the men of Mike Division. It was their courage, their love for each other that got us all through. They will always be beside me. So will Defiant Six, James Rew. He set the standards of leadership and humanity. Then there are the soldiers I met later, on the streets or in correspondence, the men who never forgot what the war was; Chip Troiano, Alan Potkin, Chuck Searcy. We the living do what we can, remembering the army of the dead. Thanks also to my cousin Mike Carlebach and editor Tom Powers for their support and encouragement. And finally, amidst all these men, I wish to thank my wife Reeve for this book in which women are otherwise so conspicuously absent. Her gentle ways made it all possible.

Contents

THE DREAM

I N THE DREAM I am at home on my farm in Vermont where I have lived since 1973. It is summertime, with blue skies, shimmering green trees, and sunshine pouring over me like warm honey. There are the rolling hayfields, the big old barn, the house Ive fixed up and filled with family. All seems well with the world; I am at peace and my children are playing in the shade of the big maple tree. I am mowing the lawn, or weeding the garden, doing middle-aged weekend things. This is always the way the dream begins.

Then there is a noise, so low and distant at first it seems more felt than heard. It is a beating, a throbbing, a drumming like the mating call of the partridge in May. But it is not the partridge, and I straighten up as I hear it. I turn left and right, trying to determine the sounds direction. It grows louder, resounding off the hills, distinctly coming from the southwest now, and I can hear the turbines, too, and separate that sound from the slapping rotors. I know they are coming for me, and there is not much time. I walk away from what I was doing and head toward a nearby knoll in the hayfields. My arms and legs get very heavy, I am so tired, suddenly so very tired, but I must go. I look back at my children playing, knowing that I may never see them again, yet there is no time to explain. Now the air is throbbing with that familiar sad song, a song I have not heard for so long. The helicopters are still hidden behind the tree line, but I know they are close now, maneuvering into a long line, preparing to descend.

I reach the knoll just as the green tadpole shapes of the slicks emerge over the trees. There are five of them, and I feel myself crying as they swing around. A smoke grenade, which I have been saving for nearly thirty years, appears in my hands. I pull the pin and throw it out in front of me, and tears sting my face as the yellow smoke billows upward. Unholy archangels, why have you come for me? Even though I am so very tired, I place my back to the wind, spread my legs slightly, and raise my arms above my head in a gesture that looks like solemn supplication. All these movements come back to me as the old circuits in my brain, so long unused, instantly rewire themselves. The line of slicks swings to my command, though my arms ache. They are downwind, bobbing gently up and down, headed straight for me. I am mindful of the power lines. I am filled with awe and sorrow. I can see the door gunners leaning out over their machine guns. I can see the sun glinting on Plexiglas. The sound wells up even louder as the machines loom closer, losing airspeed, sinking lower.

I am amused, for a moment, speculating upon what the neighbors must think. And I am pleased, for a moment, with the spectacular show Im putting on for my family. But these are fleeting thoughts. As the ships settle toward me it is mainly the sadness that keeps surging inside me, the sadness and the fatigue. Now I am engulfed by the thick, kerosene-scented wind. It is the hot breath of death. The grit blown up by the rotors stings my eyes, mixes with the tears. The incredible noise beats on my brain as the lead ship comes in, nose up, and kisses the earth with its skids. I walk toward it. The flight crew looks surreal, like spacemen, mechanical grasshoppers in their flight helmets, flak jackets and dark glasses. The infantrymen are sprawled behind them in the open compartment, sleeves rolled up over bare, tan arms, fighting gear draped on their bodies. As I approach a few of them sit up and take notice, but most continue to show the indifference of men facing combat.

The rotors thwack the air over my head. The scent of kerosene is dizzying, with that constant turbine scream that drowns out everything else. Every cell in my body is in tune. I recognize my men. One of them reaches out for my arm to help me up. It is good to feel his strength. So much time has passed, filled with the relative serenity of things we had once prayed for. But now there isnt even time to say Good-bye. The war still goes on. I must give up everything and go back. The scream gets louder and I feel the deck sway and lift beneath me. The hayfield falls away. I watch everything I worked so hard on and loved so much slowly disappear behind the skids.

In this dream my unconscious does a good job of reasoning. I know that I will be promoted to captain, and will be given a company to command instead of a platoon. It will, therefore, be somewhat safer than the last time, but still I could get killed. I also reason, as I settle in amid the web gear and feel the grenades and ammo pouches and canteens in their familiar places, that I am wiser now and less apt to take chances; better equipped to survive than the last time. But still the sadness is overpowering. I am no longer twenty-four with little to lose. Fatherhood has changed me. And I am so sad to see that the war still goes on. All that time, while I was safe at home, that war which had left poison in my veins was still going on and nobody bothered to take notice. The protesters had gone home; the television turned to other things. But for a few there can be no end, and I am tired and saddened that once again I have been chosen for this utterly awful and meaningless task. There is the sorrow that I must give up so much, my youth the first time, and now my family. There is the grief for all the people who have suffered and died while I unknowingly mowed my lawn. But I keep these thoughts to myself as I settle in among my men and feel the cool beat of the wind on my skin. We are together again, and even though I hate the war I do not hesitate for a moment.

Why doesnt a part of my subconscious rebel? Why cant I ever walk away? How is it that I can find comfort again in my compass and maps and the cool hiss of the radio, giving up all else? Or is it that the dream is real, that a part of me will always be following Highway Thirteen, which runs north from Saigon to the Cambodian border, which runs like a river through my life. I draw from it while I go canoeing. As the shore slips past, with brooding forest, beach and rock outcrop, I am also exploring the dreamscape of sandbags and concertina wire near Bien Hoa, where the road begins and trucks snort soot into the air and the black asphalt then leads to Di An and beyond, where it turns to red laterite and Herron was killed somewhere off to the right side, past the bulldozed margins of red mud and tree stumps, past rice paddies and children begging for cigarettes to the hills near Lai Khe. Then comes the open plain, then more hills and less of the sandbags and concertina wire. We cloverleaf to the left, form a column of two on the right, passing the place where Douglas and Wearmouth were killed, the highway a red stained artery dividing war zones C and D, sprinkled with the vertebrae of the lieutenant from Delta company, the land rising and falling more and planted to rubber trees, rubber trees forming patterns alongside the road which grows darker and narrower till it reaches An Loc, with the cobblestoned town square and a fountain where South Vietnamese soldiers drank beer and told stories and listened to transistor radios, and you could turn right toward Quan Loi, or keep going straight past Firebase Alpha, where Goodman and the guy whose name nobody knew got killed, and then continue farther up the road, which twists and dips and rises like a road in Vermont, the sandbags and concertina wire gone entirely, deep into the dreamscape of mist-filled valleys and little villages on stilts where the Viet Cong knew me and beckoned to me from thickets of bamboo, to the town of Loc Ninh, with its cobblestoned town square and fountain where North Vietnamese soldiers drank beer and told stories and listened to transistor radios, and where General Ware got killed, and still farther beyond, the road turning to purple clay and the shimmering green forest closing in overhead, to where the border with Cambodia is just a red and white striped pole across the road and two men stand smoking cigarettes, their bicycles leaning against the guard shack and a girl in a black and white