CAPTURED

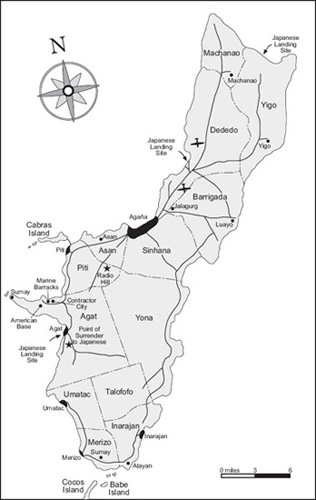

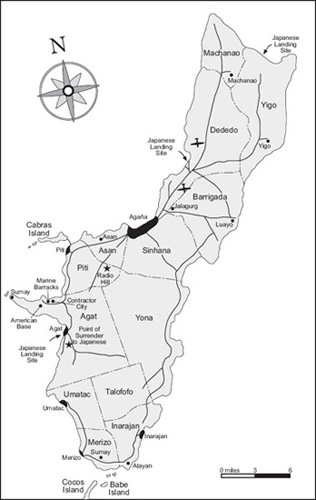

Map by Charles Grear based on original courtesy of the Gregg Collection, Hoover Institution Archive, Stanford University

CAPTURED

The Forgotten Men of Guam

ROGER MANSELL

Edited by Linda Goetz Holmes

Naval Institute Press

Annapolis, Maryland

Naval Institute Press

291 Wood Road

Annapolis, MD 21402

2012 by Carolyn M. Mansell

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or utilized in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying and recording, or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Mansell, Roger.

Captured : the forgotten men of Guam / Roger Mansell ; edited by Linda Goetz Holmes.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61251-123-8 (e-book) 1. World War, 19391945Guam. 2. World War, 19391945Prisoners and prisons, Japanese. 3. Prisoners of warJapan. 4. Prisoners of warUnited States. 5. Prisoners of warGuam. 6. United StatesArmed ForcesGuamBiography. 7. GuamHistoryJapanese occupation, 19411944. I. Holmes, Linda Goetz. II. Title. III. Title: Forgotten men of Guam.

D767.99.G8M46 2012

940.547252dc23

2012024311

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 129 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

First printing

CONTENTS

HISTORY IS ALWAYS WRITTEN WRONG, AND SO ALWAYS NEEDS TO BE REWRITTEN.

George Santayana

I n the confusing first few days after the attack on the U.S. Pacific Fleet at Hawaiis Pearl Harbor, almost 800 people, including 414 American military men and women on Guam, were taken captive by the Japanese. To secure natural resources, labor, and land for its new Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere, Japans military swept down from the home islands and across the Pacific. Within weeks Allied forces in Guam, Hong Kong, Singapore, and Wake Island were crushed by the Japanese. Newspaper headlines screamed of the desperate battle for Wake Island and of the gallantry of the men of holding out on Bataan and Corregidor in the Philippines. By the second week of May 1942, the entire western Pacific was controlled by the Japanese. The entire Philippine army and more than 36,000 Americans would eventually be in Japanese military prisoner-of-war camps. The U.S. Asiatic Fleet, stationed in Manila, ceased to exist after almost all of its ships were sunk as they fled south toward Australia. Another 125,000 Australian and British soldiers were prisoners in Malaya and Java.

The loss of the tiny tropical island of Guam, only two days after the attack on Pearl Harbor, barely created a ripple in the flood of war news. The New York Times, for instance, gave the capture only a brief mention at the bottom of the front page: Tokyo Radio declares Guam has been occupied and that the Japanese forces were firmly established there. In the histories of the Pacific war, the story of Guams defenders rarely exceeds a sentence, if thatand yet their saga is one of the most heartbreaking and inspiring of the entire war.

All of the American POWs of Guam were transported in the barren holds of the Argentina Maru to Japan and then taken directly to the Zentsuji POW camp on the island of Shikoku. In the following months and years, many were sent elsewhere in Japan to slave for Japanese industriesfamiliar names such as Sumitomo, Kawasaki, Mitsui, Hitachi, and Mitsubishi. Savage brutality, starvation, disease, and beheadings became an everyday experience for the captives.

The Japanese military had seized control of the education system forty years earlier and promoted the belief that the emperor was descended from the sun goddess Amaterasu and, as such, Japan was entitled to rule the known world. The Japanese, being superior, were entitled to treat othersthese inferior beingsas brutally as they desired. As the captives soon learned, the exception to this hatred and brutality was as rare as snow in the tropics.

The Guam POWs called themselves the Zentsujians and resolved to fight the enemy with every fiber of their being, united in a bond of hatred against the brutality of the prison guards and civilian slave masters, a brutality so unrelentingly savage that each prisoner had to make a conscious decision to survive or he would die.

By August 1945 the war in the Pacific had approached its climax as Allied forces neared Japan. The Japanese War Ministry, determined to sacrifice every Japanese citizen rather than surrender, had already ordered the execution of all prisoners upon invasion. Hatred against the West became a daily, savage brutality against the enslaved men. Equally determined to thwart the Japanese at every turn and tempered with newly developed instincts for survival, the Zentsujians made their plans to survive.

This is their story.

A s a young child on Long Island, New York, I watched uncles go off to World War II on Navy ships, followed battles with National Geographic maps, and saw a sky filled with Army Air Force planes headed to a victory flyover of Manhattan. The war was daily newsuniforms, rationing, and fast planes. I watched Civil War, Spanish-American War, and World War I veterans marching in parades. When my sister Marys husband, John Redmond, gave away the medals hed earned as a medic with General Pattons forces in Europe, I could not understand.

I studied engineering at Brown University and became an artillery officer in the U.S. Army. While I was posted to Fort Bliss in Texas, a professor at the University of TexasEl Paso introduced me to history. I wish I could remember his name, because he made history come alive for me.

Fast-forward to the day, decades later, when my employee Ken Grimes nearly spat at me when he saw Id bought a Datsun car. I knew he had been taken prisoner as a child in the Philippines, but until he explained the horrors he and his civilian parents lived through, I had no idea what it was like for guests of the emperor and why he hated anything Japanese, even a car.

In 1980 my daughters, Catherine Mansell Carstens and Alice Mansell, introduced me to their newly married high school teacher of French and German, Hildy Jarman Smith. Her husband, Maj. Gen. Ralph Smith, had fought Pancho Villa, led the first U.S. troops into World War I trenches, and taken Makin Island and commanded U.S. Army troops on Saipan in World War II. After the war, he had run CARE programs in Europe with the help of a young assistant named David Rockefeller.

Ralph discovered my interest in history and insisted I join him for weekly lunches at our local American Legion post. He opened my eyes to a new way of looking at history; hed lived it from the trenches to the highest level of international politics. Through him I started to meet and interview veterans whose stories were being forgotten.

I began to attend gatherings of the American Defenders of Bataan and Corregidor and the Zentsuji survivors reunions. Soon I was assembling POW camp rosters and death and survivor lists, and I created a website, www.mansell.com, to share this data. As I gathered more stories, I realized no one had written much about the military and civilian personnel captured on Guam in the early days of the Pacific war; this became my mission for the next ten years.

I am in debt to the late John Taylor, chief researcher at the National Archives Modern Military Records in College Park, Maryland, and to the reference room staff there. Researchers such as Dwight Ridder and Wes Injerd (who now maintains my website) have helped me greatly.

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).