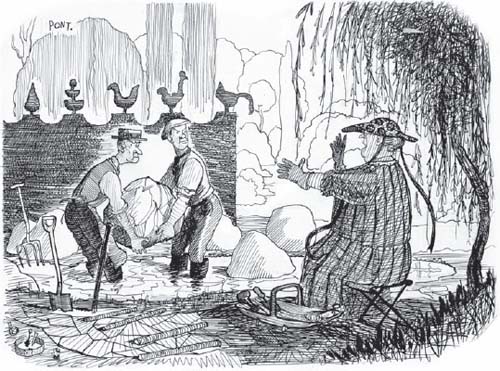

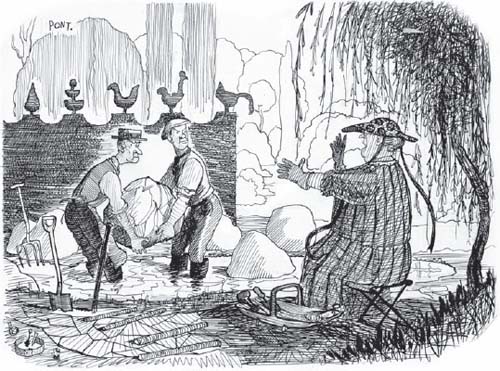

T HE B RITISH C HARACTER

Enthusiasm for Gardening,

Pont (1938)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Horwood, Catherine.

Women and their gardens: a history from the Elizabethan era to today / Catherine Horwood.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-1-61374-337-9 (hardcover)

1. Women in agriculture. 2. Women gardeners. 3. GardeningHistory. I. Title.

HD6077.H67 2012

635.082dc23

2011046472

Copyright Catherine Horwood 2010

All rights reserved

Published by Ball Publishing

An imprint of Chicago Review Press, Incorporated

814 North Franklin Street

Chicago, Illinois 60610

ISBN 978-1-61374-337-9

First published in the United Kingdon by Little, Brown Book Group

Interior design: M Rules

Printed in the United States of America

5 4 3 2 1

This book is dedicated to the memory of my stepfather, Vivian Milroy, who died just before its completion. He was delighted to know that it combines two things that had given him such pleasure during his long life gardening and, especially, women.

PLANT NAMES AND SPELLINGS

In direct quotations apparent misspellings have been used as they appear in the original texts.

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

A s a child, I thought I hated gardening. I grew up listening to my mother and my aunt comparing the relative merits of Clematis Marie Boisselot and Clematis Henryi, or endlessly agonising over blackspot on roses with unpronounceable names such as Cuisse de Nymphe and Gruss an Aachen. In those days it was all Greek to me, but once I had a garden of my own everything changed. Gardening became a shared passion, so that a walk with my mother around either of our gardens inspecting new treasures became almost as important to us as an update on her grandchildren. Now the first of those grandchildren, my eldest daughter, has a patch of her own and e-mails her pride in a new plant grouping while vowing never to eat a supermarket tomato again. The bug has bitten once more and the legacy continues.

We are far from unique in being a family of gardening women. Why then are women so rarely celebrated in the history of gardening? Ah, Gertrude Jekyll, said friends knowingly when they heard what I was researching, as though she had been the only woman ever to have made a contribution to gardening worthy of note. People who know a bit about the subject may mention a few more recent names such as Vita Sackville-West or Beth Chatto, but the overriding assumption is that women contributed nothing to the garden before Jekyll and very little since. This is an attempt to correct these misconceptions, telling the stories of those who have been most involved, and putting on record that for centuries gardens have been important to women and women have been important to gardens.

Arguably, women were actually the first gardeners. Evidence from the earliest human settlements suggests that, while men went away to hunt, women harvested and, eventually, cultivated the nearby land, which became a kind of kitchen garden. Once more stable societies with larger-scale agriculture developed, men no longer had to leave their homes for days or weeks on end to find food and women lost most of their influence over plant cultivation. Nevertheless, in mythology, the Roman deity of plants was the goddess Flora, whose Latin name is the root of flower. Christianity has associated women with gardens since the story of Eve in the Garden of Eden, and during the Middle Ages the hortus conclusus, or enclosed garden, was strongly linked with the Virgin Mary and the garden of Paradise.

Throughout the medieval period, all classes of women were involved in horticulture, growing flowers and vegetables for food and medicines.

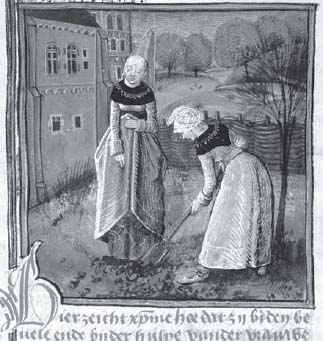

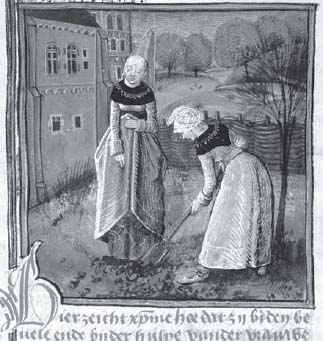

In reality, women have had a long involvement with plants and gardening although their contribution has evolved over the centuries. In medieval art, women are sometimes depicted tending plants, perhaps sowing or weeding, but there are scant references to them in the written records, and when they do appear they are usually anonymous. The reason for this lack of written evidence in earlier centuries is in part due to individual women being deemed unworthy of mention unless they were of high rank, but it is also because the gardening work they did was menial and either unpaid or rewarded only with a pittance. However, what they undertook was vital, since they were responsible for many of the traditional tasks which put food on the table: indeed, they were judged on their ability to do so.

As with those who used their skills and labour to supply their kitchens, there are few direct records of women gardening for pleasure before the sixteenth century and those who do appear are in the upper strata of society. In the early twelfth century there is an abbess, aunt to Henry Is wife Matilda, who grew roses and other flowering herbs in the convent garden. Three medieval Queen Eleanors were recorded as keen gardeners: the garden of Eleanor of Aquitaine, wife of Henry II, has been recently recreated behind the thirteenth-century Great Hall in Winchester; Eleanor of Provence encouraged her husband, Henry III, to develop the gardens at all his royal residences; and in 1279 Edward Is wife, Eleanor of Castile, brought her own gardeners from Aragon to create a garden for her at Kings Langley in Hertfordshire.

There are no other details of Sabines gardens, but from this point on we start to learn more about other womens involvement in horticulture, and it is here that I begin the story of women and gardening. It was a time of political unrest, but also of discovery and exploration, with exciting new plants arriving from the Americas and the Orient. Scientific curiosity, technical advances in printing and improved techniques helped to quench the thirst for horticultural knowledge, for the first time accessible to both sexes, and this era can fairly be said to mark the start of women being able to fulfil their desires to create their own gardening worlds.

All the women gardeners who feature in these pages have left a rich and rewarding legacy, from the collectors of once-rare plants that are now available in every garden centre to the pioneers of design whose individual genius can be traced in landed estates, city parks and suburban patios.

Why do women garden? Gertrude Jekyll, or the Queen of Spades as she was called when receiving her RHS Victoria Medal of Honour in 1897, believed that the appeal of gardening lay in giving happiness and repose of mind, firstly and above all other considerations, and to give it through the presentation of the best kind of pictorial beauty of flower and foliage that can be combined or invented.

Catherine Horwood

A PASSION FOR PLANTS

One can never know too much about a plant;

one never can know all there is to be learnt.

Frances Jane Hope,

Wardie Lodge, near Edinburgh (1875)

Next page