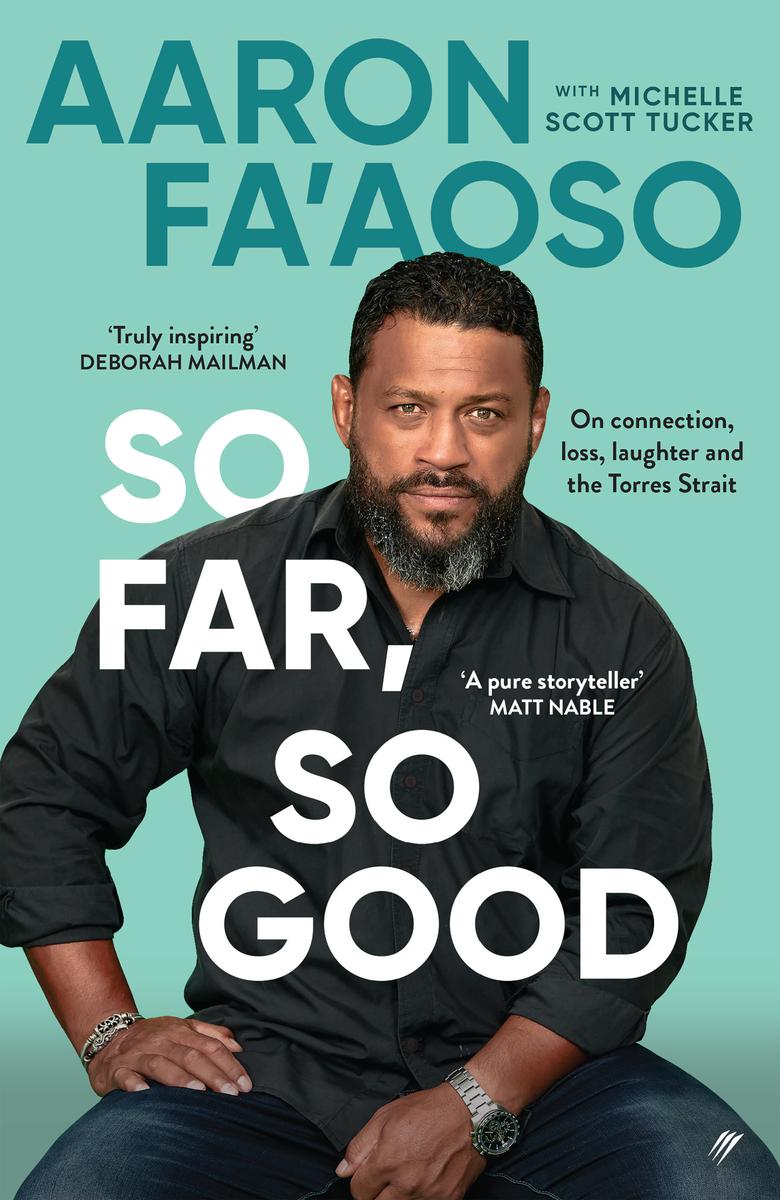

On his long path to success from aspiring professional footballer to actor, director and producer for every opportunity Aaron FaAoso had, there were setbacks and heartache.

He was six when his father and grandfather both died. His fiercely proud mother and even fiercer grandmother dug deep to raise Aaron and his brothers. Belief in himself as a warrior literally and metaphorically made him into a fighter, for better and for worse.

A month into Aarons second marriage, and just as his acting career was flourishing, his new wife took her own life. In the dark years that followed, Aaron eventually found strength and meaning in his family and in his beloved Torres Strait community.

Lets begin the story

He was taller than me, a couple of years older too. Kids around us had started chanting: fight, fight, fight, fight, fight. School had just finished for the day and there were children and parents everywhere. I probably should have thought that through a little better.

He snarled, full of menace and bravado yet pale and sweating in the tropical Cairns heat, saying something like, Cmon cunt, Ill have ya.

I ignored the noise and his bluster and instead sized him up, estimating the length of his reach, calculating where I would strike first. Usually somewhere unexpected. Not the head everyone always goes straight for the head.

At 15, I already had years of martial arts experience behind me, regimens of barefoot running and full-body sparring that these days would be considered more like child abuse than training. Add to that my fitness from footy, basketball, pushbikes and swimming if it was daylight I was moving, or wishing I was. And, thanks to my Tongan dad, I was a big, solid kid.

I hit him first. He was ready for me, though not ready for how hard my fist was or how much it hurt. To his credit, he came back at me with everything he had but I didnt feel a thing. This kid had stolen a bike from a little boy, my cousin, and had failed to return it when asked nicely. So I wasnt asking nicely anymore. I was filled with rage and fought with a righteous fury.

Somewhere along the way the kids friends joined in, and then my younger brother, and it quickly turned into a melee. Some brave parents weighed in, trying to break it up, but we were fighting like dogs and it was too dangerous to pull us apart.

The fight ended with the other kid on the ground, not moving much. My brother and I picked up our school bags and walked away like kings, high on adrenaline and what we considered justice. He wasnt going to steal from a blackfella again. No-one tried to stop us, even though we had basically just put someone in hospital. But we were both in our school uniforms and people knew who we were.

I probably should have thought that through a little better too.

The repercussions of the fight started that evening. I told Mum what had happened as soon as she came home from work. She was quite rightly furious, so that didnt go too well. Yet she wasnt so upset that she failed to see into the heart of the matter.

Did you get your cousins bike back?

Yes. I got his bike back.

That wasnt nearly enough to get me off the hook, though. When she subsequently told some of my uncles about the fight, and my nan, that didnt go well either. They all wanted a piece of me.

And within a day or two I was called into the principals office. That really didnt go well. Id not yet finished Grade 10 but he wanted me gone. Expelled. Piss off and dont come back. Any future I might have had was shrivelling up fast.

Looking back, its surprising the police werent involved. Maybe the other kids family were worried about the stolen bike. Maybe someone within my extended family had put a word in with the right people. Or maybe given that Bjelke-Petersen had not long been out of office and Cairns was still, well, Cairns the cops simply couldnt be bothered.

My righteous fury had fallen away almost immediately, and in its place was a sense of sorrow. Like any 15-year-old in hot water, I felt sorry for myself, but I increasingly felt sorry for the other kid too. Id hurt him pretty bad. A week or so after the fight, without any prompting, I went around to his parents house and apologised.

But it was to Mum and Nan that I most needed to say sorry.

Theyd brought me up to be better than some schoolyard brawler, to know better. They wanted me to make something of myself. Every day, through a thousand practical actions, they taught me about right and wrong, but they were lessons I was destined to learn over and over again usually the hard way.

Women of the Samu (Cassowary) and Koedal (Crocodile) clans, from the Torres Strait, Mum and Nan are proud descendants of generations of Melanesian warriors. Strong, and fierce with it, they are the toughest women I know. The most loving too.

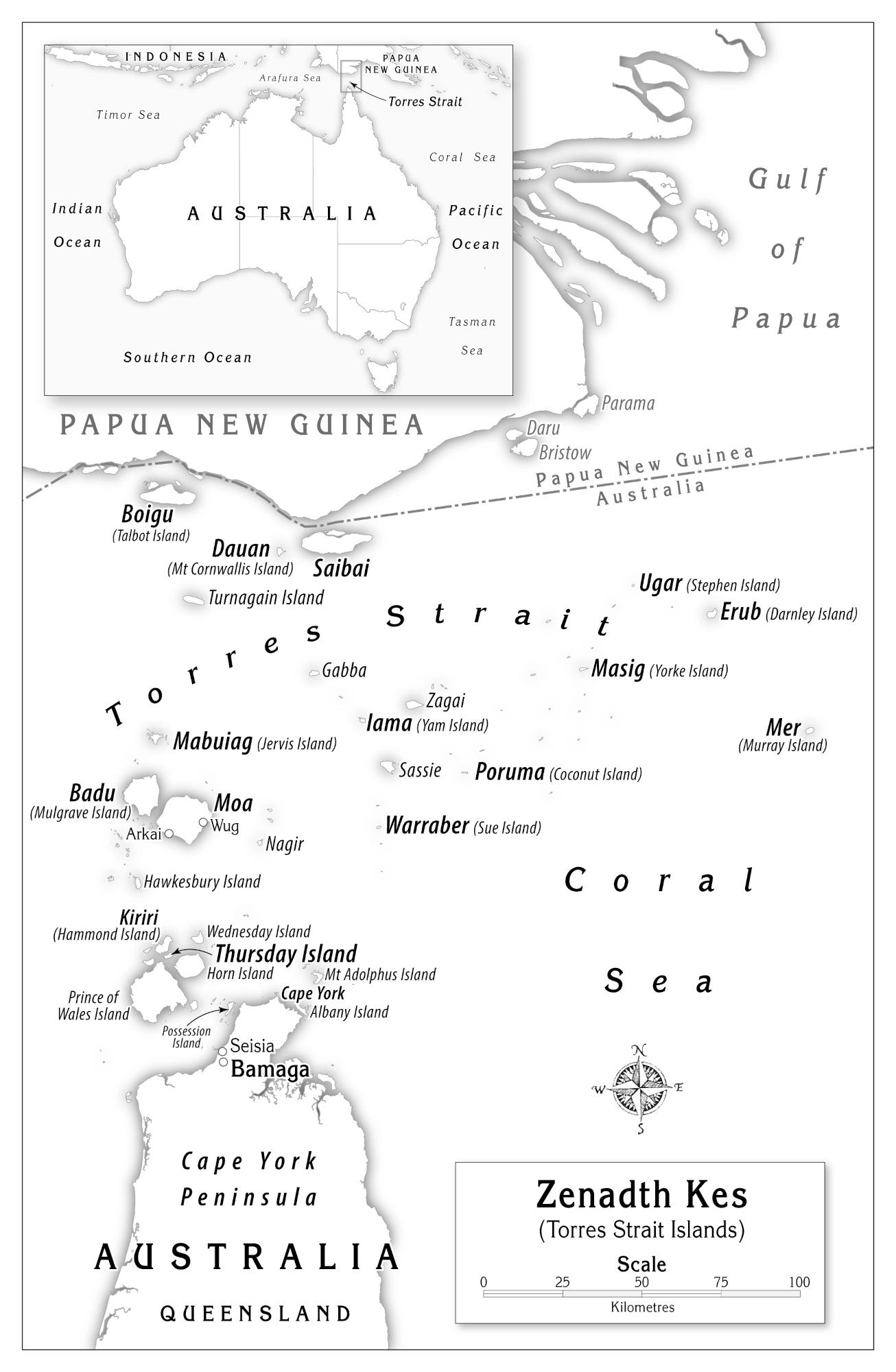

My nan, Mary-Betty Harris, was born on Saibai, a large, low-lying Australian island only about four kilometres south of the Papua New Guinea mainland. In 1947, when Nan was a teenager, king tides flooded the island, submerging the main village under metres of water. For the people of Saibai, it was only the latest in a series of environmental challenges. The community had been suffering from the effects of erosion and the impact of salt on their crops and freshwater supplies for a long time.

After much discussion, many Saibai families decided to move permanently to the Australian mainland to the tip of Cape York Peninsula, about 170 kilometres south. Within a year, the Queensland government gazetted 18,000 hectares as a reserve for the use of Torres Strait Islanders. By the early 1950s, a settlement was established, called Bamaga in honour of the Elder, Bamaga Ginau, who had led the migration discussions but who had not lived to see the results.

Basically, my nan and her family were Australias first climate-change refugees.

They were among the community pioneers who worked in Bamaga to clear the land and to establish agricultural enterprises to feed their families, and who built a settlement from scrub, from nothing. Theres something about taking that untravelled road thats instilled in me, something about being born from that legacy. Now we, their descendants, are responsible for the land, for the community. Im choosing my words carefully here its not our land, we are not the Traditional Owners, but its very much our responsibility.

For about 20 years, Nan lived in Bamaga with her family, and then with Grandad. She had a daughter her only child, Delilah Elizabeth, my mum. Nan was determined that her girl would receive a solid education. At what now seems like a ridiculously young age, Mum was sent to an Anglican boarding school for the first years of her education. Then in 1968, when Mum was 13, Nan and Grandad moved south again, this time to Cairns, so that Mum could go to school there.