Contents

Guide

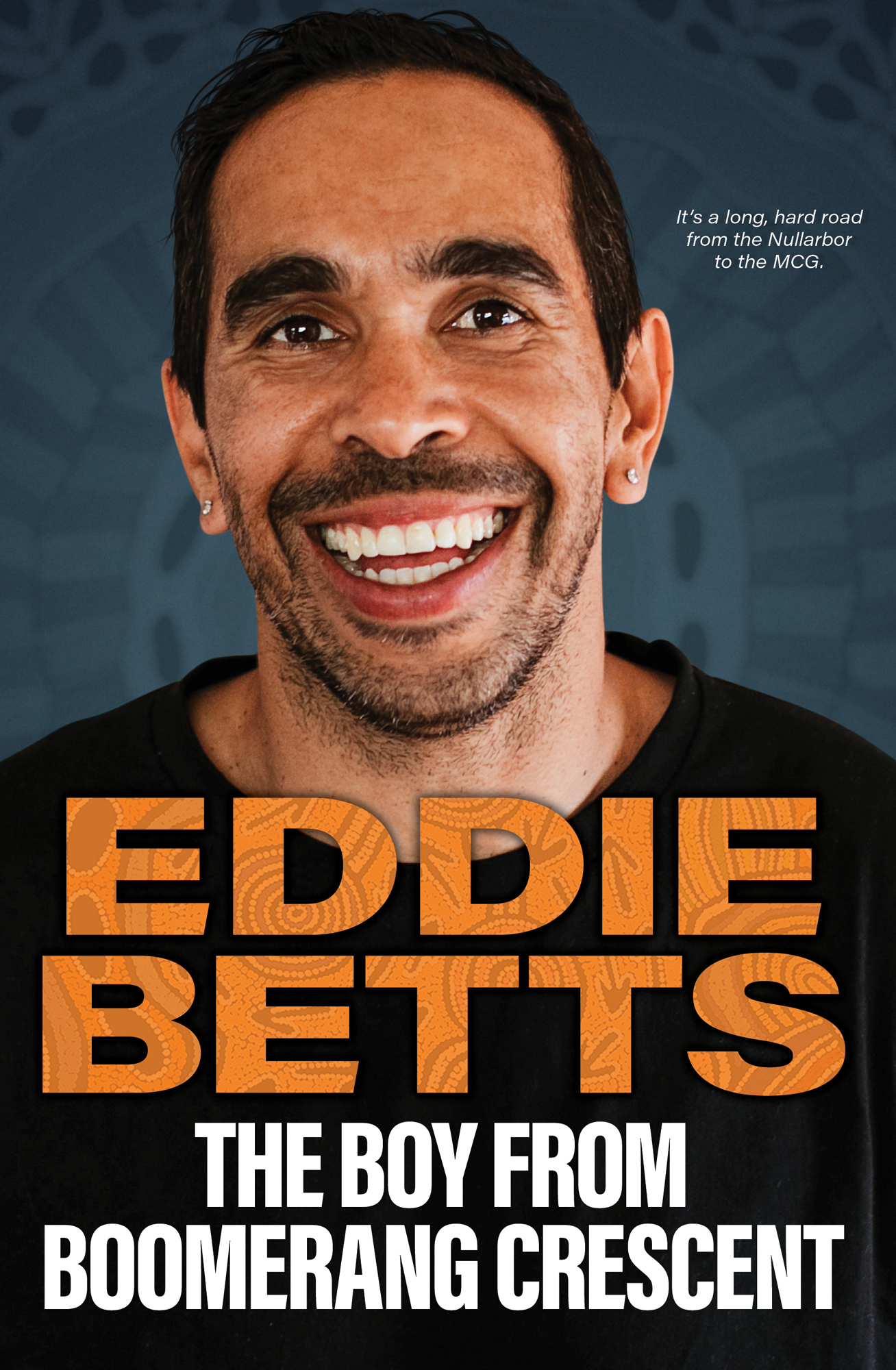

Its a long, hard road from the Nullarbor to the MCG.

Eddie Betts

The Boy from Boomerang Crescent

For my mob.

It takes a village and without that village I would never be where I am today.

Thank you for the sacrifices you made for me.

FOREWORD

I first met Eddie Betts in person whilst I was working as the Indigenous Program Manager at AFL Victoria in 2010. Our offices were based at Optus Oval, the home ground and training venue for Carlton Football Club.

It was a chance introduction. I was walking around the outside of the ground with my father, who is a lifetime-devoted Carlton supporter he was just thrilled to be at the home of his beloved Blues. As we were walking along, just chatting, we noticed Eddie walking along by himself just outside of the gate where the players enter the venue. When Eddie saw us, other Aboriginal people, he stopped and waited.

I introduced myself and I also had to introduce my father as I thought that he was going to be too awe struck to speak. My father eventually mentioned that he was a lifelong supporter of the Blues and of Eddie.

For the next 10 minutes Eddie Betts made my father feel like he was the most important person in the world. The respect that Eddie showed, the genuine interest in who my father was and where he was from, was amazing to witness. I took a few ripping photos of Dad and Eddie together, one of which still holds pride of place in his home today.

As we were saying our goodbyes and best wishes, Dad and Eddie shook hands like only us Aboriginal community do and they shared a cuddle that meant the world to my Dad (and I suspect to Eddie too).

As we were walking away, I looked at my father and noticed a smile from ear to ear and a real bounce in his step. His moment of pure joy had just happened. Following this meeting, I always had a special interest in following the career of Eddie Betts because I knew that he was a genuinely respectful young man.

In February of 2018, I was working as the Indigenous Relationship Manager at the AFL Players Association, and we were gathered at the Bi-Annual AFL Indigenous All-Stars Camp in Adelaide where all Indigenous players come together for a week-long camp of football, Culture and connectedness.

At this camp I witnessed a moment in time that has changed the landscape of sport in our country forever, with regard to how racism is now dealt with. This is the time that Eddie Betts took the opportunity at our hotel venue to speak to all his Indigenous peers as a group. He stood, and then paced, whilst commanding the attention of all within the room, and he implored all his brothaboys From today onwards when we hear racism, we all call it out or nothing is going to change.

Eddie challenged the room multiple times to better gain an understanding of who was with him and whether he had their full support. In the end, the decision was made unanimously by all attending Indigenous players, along with full support from the AFL Players Association and the AFL. Eddie Betts is the one person responsible for creating positive cultural change by taking the responsibility to bravely challenge his peers to no longer accept racism.

I truly admire Eddie as a person and a father, for his strong leadership capacity, resilience and desire to make our country better for all.

Leon Egan

We used to play spot the eagles as we flew across the Nullarbor in our little two-door Magna. Wed spot them circling over the highway and count them sitting on the dead kangaroos by the side of the road. Mum always had the trip mapped out and planned ahead. Sometimes wed do the drive non-stop. Wed stock up on music cassettes at the servo country music mainly, like Alan Jackson, a bit of Creedence, John Fogerty. Then wed play the cassettes on repeat for two days. Other times wed pull up and get a motel room in Border Village, home of the Big Roo on the South Australia Western Australia border. What I remember most is the long, flat drive, the eagles, sometimes a camel out on the plains or some emus, the kangaroos along the road, and the trucks that wouldnt stop for anything.

I loved those trips. Theyd take a couple of days. We used to pull the seats out of the back of the Magna, put a mattress in the boot and away wed go. Itd be Mum, me and my two sisters, Sarah and Lucy, shuttling across the Nullarbor between Kalgoorlie and Port Lincoln. Wed always get somebody to come along with us to share the driving with Mum. We were always squeezing people in.

During the long drive wed play games to break up the time. Car cricket was popular I remember red trucks were an out, and the blue cars were fours. Id also take my mind off things by playing with a couple of little teddy bears. I would lay-up on the mattress and pretend they were playing footy, taking screamers and hangers. Before I knew it five hours would have passed. My imagination took me onto an Aussie Rules ground, thinking of my family, being like my Uncles playing in the Blackfulla carnival.

Im not the first Eddie Betts. Im not even the second. Im also not the first to play football. I might not even be the best footballer to have carried the name. Edward Frederick Betts, my grandfather, was born on South Australias west coast and lived there most of his life before he died on the floor of a Port Lincoln prison cell.

He came into the world at the Koonibba Mission on 10 March 1938 and lived in the childrens home there. Back then, they called it a native home. It was supposed to develop the next lot of workers for the area. My grandfather and the rest of the kids were westernised, taught to be reliable Christians. Eventually, his dad my great-grandfather moved the family to Cummins, a little wheatbelt town on the Eyre Peninsula. He made money by doing all sorts of different things there, including moving wheat along the railway line.

They reckon wheat lumping was tough. Once the grain was sewn into jute bags, the lumpers had to throw the bags up on their shoulders some of them were as heavy as 90 kilos and get them in and out of the storage terminals. Lumping was so important to the history of the area that theres a bronze statue of a lumper in Cummins now. Eddie followed in his dads footsteps and became a lumper, too, in nearby Ceduna. He also played a bit of footy for the Rovers there, which is how he met his wife, Veda. They married in 1959.

Whenever you talk to people who can remember my granddad, they all mention how brilliant he was at football. He won the Mail Medal in 1958, given to the fairest and most brilliant player in the entire country association. He and Veda had two children while they were living in Ceduna.

When the North Whyalla Football Club asked Eddie to come and play for them, he packed up the family and headed east on a bus. Unfortunately for North Whyalla, their rivals, the West Whyalla Dragons, got wind of the trip and sent a group of players some 150 kilometres to intercept the bus at Kimba, about halfway between Ceduna to Whyalla and by the time they reached Whyalla, Eddie was signed to be a Dragon and had the promise of a better job at BHP.

He played with West Whyalla for a few years, and during that time another one of my Aunties was born. But pretty soon the family was off to Port Lincoln, after Eddie was chased by the Tasman Football Club, where he got to play with his brother George Burgoyne. I only mention that because in most of the teams he played for, Eddie was the only Blackfulla on the team. He only played until 1968, because at the end of that season he was sent to hospital feeling unwell. He ended up being diagnosed with high blood pressure. He must have been gutted to have to stop playing footy, but he was left with no choice and forced to retire. By then, he was generally seen as one of the best Rovers the Far West Football League had seen.