About The Author

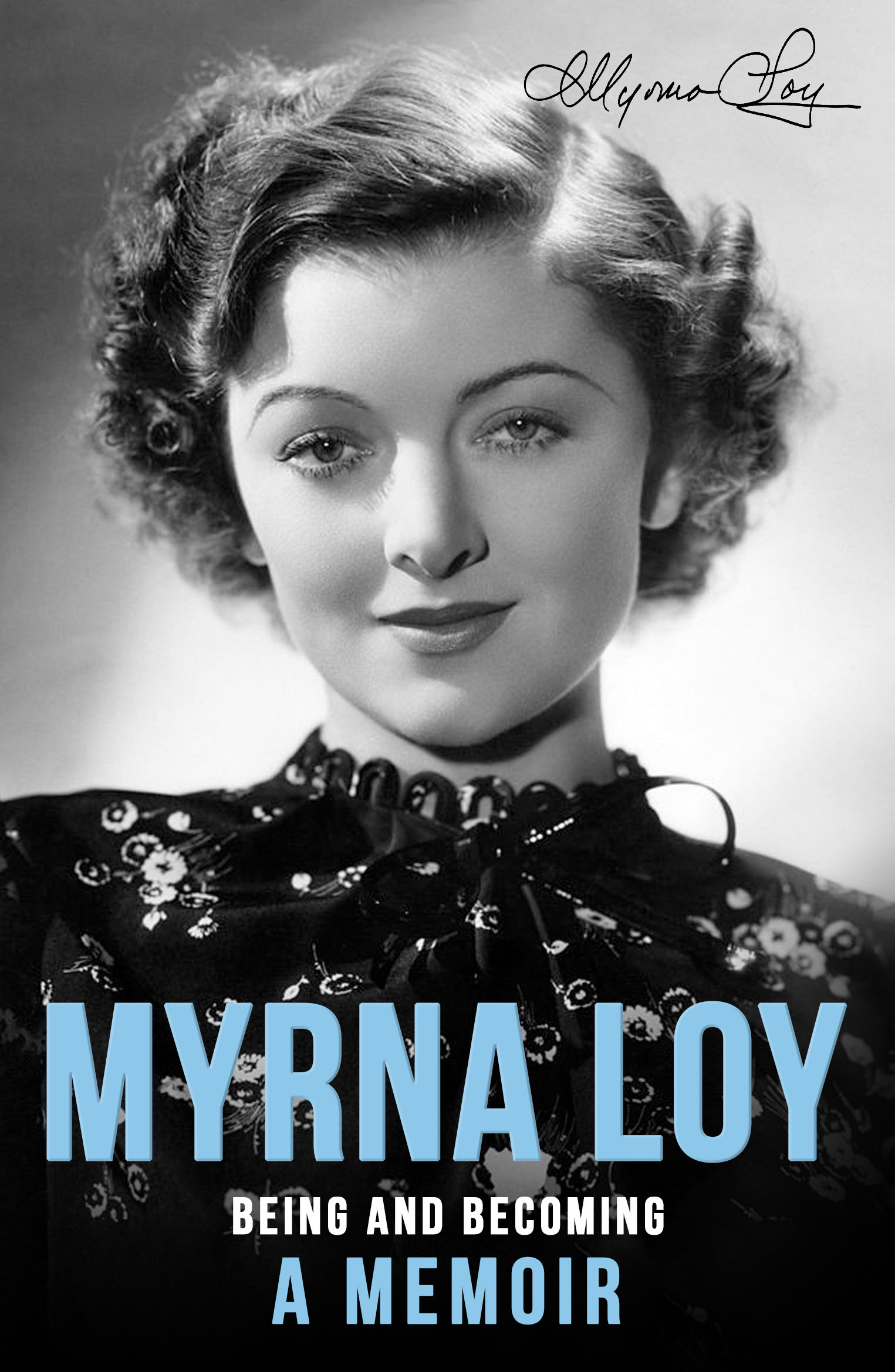

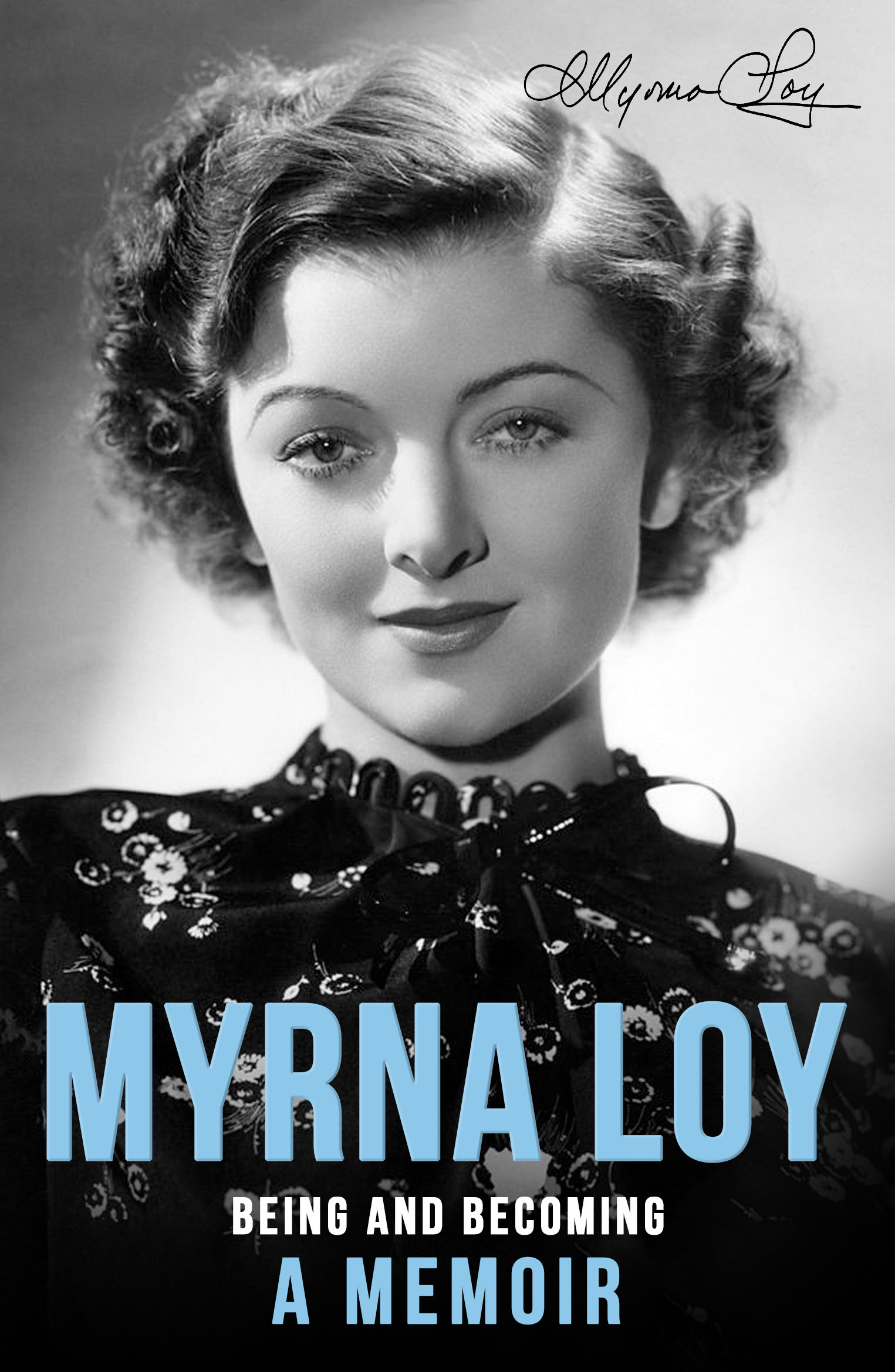

Myrna Adele Williams was born in 1905 in Helena, Montana. She was raised a Methodist.

After relocating permanently to the Los Angeles area aged 13, Myrna attended Westlake School for Girls, and later Venice High School, while intensively studying dance .

Myrna made her first film in 1925, and appeared in numerous silent movies throughout the rest of the 1920s. Having successfully made the transition to talkies, her big break came in 1934 when cast as Nora Charles in The Thin Man , opposite William Powell. She subsequently became one of Hollywoods most popular actresses throughout the remainder of the 1930s, the 1940s and 1950s.

During World War Two, Myrna became increasingly involved in politics, initially as an outspoken critic of Adolf Hitler. She later became a member of the US National Commission for UNESCO, and actively supported the nomination of several Democratic candidates.

Myrna married four times, each union ending in divorce. In 1960 she moved to New York City, and continued to appear in movies and television productions. Her last motion picture was Sidney Lumets Just Tell Me What You Want in 1980.

In 1991 Myrna won an Academy Honorary Award, presented by Angelica Huston. She died in New York, aged 88, in 1993.

Published by Dean Street Press 2021

Copyright 1987 Myrna Loy

Introduction copyright 2021 Imogen Sara Smith

All Rights Reserved

First published in 1987 byAlfred A. Knopf

Cover by DSP

ISBN 978 1 914150 82 1

www.deanstreetpress.co.uk

INTRODUCTION

Anyone can be witty if they have good lines written for them, but Myrna Loy could be witty without saying a word. Wit was etched on her face, as though her sharp, lively mind worked on her features from within: the arch of her eyebrows, the sly narrowing of her eyes, the tilt of that famously enchanting nose. (Plastic surgeons were besieged by women clamoring for a copy of it). Before she opens her mouth you know she has a wicked sense of humor, and a warmth that lies just under her cool, oblique reserve.

For lovers of old movies, Loy embodies the 1930s in all their effervescent, streamlined glory, yet her performances are so fresh and true they could have been shot todayor tomorrow. She is not an actor who needs juicy parts, big scenes, or dramatic speeches to make an impression; she listens and observes, and works such wonders with the tiniest expressions that while her co-stars may hog the spotlight, shes the one you cant take your eyes off. In The Best Years of Our Lives , for example, Frederic Marchs flamboyant drunk scenes are topped by her low-key mix of rueful wifely tolerance and sneaking enjoyment. She understood the nature of cinema acting: that the camera can capture thought through the eyes, and also that the camera will grotesquely magnify any artificial gesture. Her style is dry, like sherry, and subtle, like a tantalizing whiff of the finest perfumeintoxicating, scintillating, but elusive. She always leaves you wanting more. As critic James Harvey wrote in his magisterial study Romantic Comedy , Loys glamour on the screen seems always related to meanings held back, diffused, refracted. Her expressiveness, which is considerable, is indirect, light, oddly angled.

This is especially noticeable in her partnership with William Powell. Even more than quips and banter, their magical rapport lies in the ways they react to each other: her precise shadings of skepticism, surprise, and contained amusement, his double-takes of incredulous delight. At least once per filmthey made fourteen togetherhe looks happily gobsmacked, momentarily speechless at his good fortune in being with this woman. The perfect wife label that was attached to Myrna Loy is dated and patronizing (no one called Powell the perfect husband, though for some he might be). In fact, the secret behind Loys enduring popularity was always that she appeals to women and men equally, as attractive a friend as a mate. Yet the picture of marriage these two presented, at least in the early Thin Man movies and the best of their thirties comedies, still feels modern: a harmonious partnership spiced by equality, teasing, and just a dash of competitiveness, nourished by a ceaseless wellspring of private jokes. Their appreciation of each other is protected by a slight touch of formality and detachment that preserves their glamour. It is all pure fantasy, of course, a dream-world where it is eternally cocktail hour and even hangovers seem chic and funnybut who wouldnt aspire to such an ideal?

By the time she made her legendary entrance in The Thin Man (1934), landing with a splat on a nightclub floor and picking herself up to order six martinis with a graceful flick of the wrist, Loy had already appeared in more than eighty films, and she would rack up some sixty more movie and TV credits, and carve out a whole second career on the stage, from summer stock and dinner theater to Broadway and national tours. With reserves of energy and discipline inherited from her pioneer grandmothers, she was also a passionate activist for progressive causes and a tireless campaigner for left-wing political candidates. The air of substance and purpose she conveys on screen, even when relegated to playing wives and sweethearts, was no illusion, as her autobiography makes clear.

Loy was one of the first actresses to rebel against a Hollywood studio when she staged a one-woman strike in 1935 over the poor roles she was getting and the fact that she was earning half Powells salary on their films together. MGM caved in to her demands and even gave her a bonus to lure her back. She was also one of the first Hollywood stars to be smeared in the anti-communist witch hunt that began in the late 1940s, and again she fought back: taking a page from her character in Libeled Lady (1936), she sued the Hollywood Reporter for a million dollars and won a groveling retraction. Though never a communistshe was staunchly opposed to all forms of totalitarianismshe was outspoken in her disgust at the Hollywood blacklist. Always ahead of the curve, she was an early supporter of civil rights and co-chaired a national committee against discrimination in housing. After World War II, she became deeply involved with the United Nations and UNESCO: not merely lending her name or face for publicity, but attending international conferences, plowing through stacks of dry documents, and giving speeches to tough crowds of snobbish diplomats. She said it gave her greater fulfilment than her film career, yet she recognized that what she could offer was the power of cinema to reach the broadest audience and sell peace as a dramatic, positive idea.

Originally published in 1987, Myrna Loy: Being and Becoming is one of the most irresistible and satisfying Hollywood memoirs, thanks to Loys frank, lucid, and piquant voice. So many movie stars were radically different in real life from their screen personas that it is a shock to discover from this book how much Loy resembled hers: elegant and spirited, clever without being catty, wise but never sanctimonious. She is in the truest sense a lady, able to mix poise with the occasional pratfall, able to make being grown upsane and self-possessedalluring and sexy. No one in the movies is grown up this way anymore; no one, it seems, even aspires to be.

You might think it would get tiresome to read about someone who seems to have been so universally admired, so short on flaws, and whose life was in many ways, despite a grueling work schedule and four failed marriages, so privileged and charmed. Yet it is impossible not to like Myrna Loy and root for her, to feel she deserved all the bouquets and adulation, the beautiful homes and high-society frolics. She certainly worked hard for them. She can even make goodness interesting, and that is a gift the world could use more of. As Frank S. Horne, Lena Hornes uncle and Loys colleague in the fight for racial justice, put it, she added delight to conviction. Not for nothing does her name rhyme with joy.