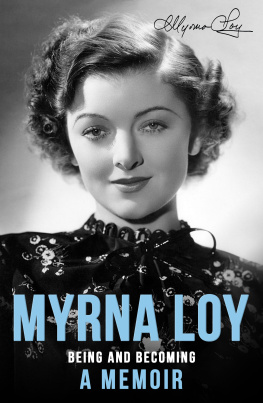

Myrna Loy

Myrna Loy

The Only Good Girl in Hollywood

Emily W. Leider

University of California Press, one of the most distinguished university presses in the United States, enriches lives around the world by advancing scholarship in the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences. Its activities are supported by the UC Press Foundation and by philanthropic contributions from individuals and institutions. For more information, visit www.ucpress.edu .

University of California Press

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

2011 by Emily W. Leider

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Leider, Emily W.

Myrna Loy : the only good girl in Hollywood / Emily W. Leider.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-520-25320-9 (cloth : alk. paper)

1. Loy, Myrna, 19051993. 2. Motion picture actors and actressesUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

PN2287.L67L46 2011

791.43028092dc22

Manufactured in the United States of America

20 19 18 17 16 15 14 13 12 11

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

In keeping with a commitment to support environmentally responsible and sustainable printing practices, UC Press has printed this book on Natures Book, a fiber that contains 30 percent postconsumer waste and meets the minimum requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (R 1997) (Permanence of Paper).

For Rosa and Linus,

a new generation of movie lovers

Contents

Plates

Introduction

Myrna Loys grace and slender elegance, her ease before the camera, and her arresting face had a lot to do with her success on film, but she claimed that stardom entailed more sweat than glamour. In her early days at Warner Bros. she worked nonstop, sometimes moving from set to set in multiple films being shot at the same time. In 1927 alone she played in eleven movies, and she took no vacation until she had been a screen actress nearly ten years. During her six-decade career she appeared in a staggering 124 films, beginning with her debut at age twenty as a dancing chorine in Pretty Ladies. Fifty-five years later, in 1980, she made her last appearance on the big screen, as a sassy executive secretary in Sidney Lumets Just Tell Me What You Want.

Loy took her first full-time job, as a prologue dancer at Graumans Egyptian Theatre, while still in her teens. She needed to support her widowed mother, younger brother, and aunt. As a contract player for Warner Bros. in the 1920s she took part in the sound revolution, playing small roles in Don Juan, the first silent with a synchronized score, and The Jazz Singer, the groundbreaking Al Jolson musical with some sound dialogue. Hitting her stride in drawing room comedy in the early sound era, she signed with MGM in 1931, striking gold three years later as Nora Charles in The Thin Man and making the list of the top ten box-office stars in 1937 and 1938. After taking time off to move to New York and volunteer full time for the Red Cross during World War II, she returned to Hollywood for a memorable performance opposite Fredric March in The Best Years of Our Lives, winner of the Best Picture Academy Award for 1946.

Along the way, in her eighty-eight years, she found the time to marry and divorce four times, fight the House Un-American Activities Committee, become a UNESCO delegate, campaign for various Democratic Party candidates, serve John F. Kennedy on the National Committee against Discrimination in Housing, help found the American Place Theatre, and rack up credits in radio, television, and stage. She lived in four very different citiesHelena, Montana; Los Angeles; Washington, D.C.; and New Yorkand traveled widely. She could always see the larger world beyond Hollywood.

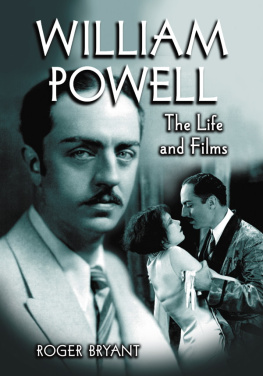

As a screen actress Loy was best known for her collaborative skills. She was an attuned, responsive screen partner, most famously to William Powell, with whom she made fourteen films, but also to Clark Gable (her second most frequent leading man), Cary Grant, Melvyn Douglas, and a long list of others. Never a stand-alone pillar of female power onscreen, she excelled at sharing the frame and reacting, what Cary Grant called tossing back the ball. Here she differed from her dynamo friend Joan Crawford and from such dominating female screen icons of her generation as Bette Davis, Katharine Hepburn, and Mae West. Being a top-tier movie star didnt define Myrna Loy as it did them, and her career eventually lost momentum as a result.

Most at home in comedy, she achieved her best effects by underplaying, by suggesting meaning rather than hammering it home. No pies in the face for her. The subtle, nuanced action or reactiona raised eyebrow, wry inflection, or crinkled nosecould say it all. Even in drama she avoided scenery chewing or broad strokes. For Loy, as an actress, less was more. Extremely modern in her minimalist technique, she remains our contemporary in her ability to grow, to stay in the game and continue evolving.

Her greatest acclaim followed the unexpected runaway success of her partnership with Powell in The Thin Man, which engendered five sequels. Released just months before strict enforcement of the Production Code began, The Thin Man pleased censors by making marriage, the only kind of sexual relationship endorsed by the Code, look like fun. Because Nick and Nora Charles lived a carefree, luxurious life on buckets of money, they made married life look like one big party, with plenty of excitement generated by a murder mystery and enough mink coats, art deco surroundings, martinis, and smart repartee to divert any Depression-weary audience. The screens Nick and Nora turned wedded bliss into a true partnership of near equals. Although Nick dominates and sometimes condescends, Nora holds up her end. She has wealth, wit, style, and a mind of her own. This kind of balance between complementary spouses had never been shown onscreen and became a model for subsequent couplings in cinema and television.

Comedy itself changed over the decades of Loys career. The cynical, urban edge of the first Thin Man became less cutting in the sequels, and the mingling of wealthy characters with endearing ex-cons no longer worked. Nick and Nora acquired a son and stopped being footloose. During World War II, family values took hold, and murder could no longer be treated lightly. The postwar comedy Mr. Blandings Builds His Dream House played to the consumers dream of achieving happiness by buying a house in the suburbs and fixing it up with multiple bathrooms.

Nora was consistently a good sport, and usually upbeat, as was Myrna Loy offscreen. Although she once took on MGM, going absent without leave and demanding higher pay and more time off, and although from the 1940s on she sounded off periodically against isolationists and right-wingers, in private she usually shunned confrontation, as did the characters she played. In After the Thin Man William Powells Nick tells Nora: You dont scold, you dont nag, and you look too pretty in the morning. Nora wryly promises to start scolding, but she never does.

Myrna Loy had a well-spoken, relaxed but classy manner that eventually steered her into genteel roles, usually as someones wife. Darryl Zanuck tried to put her in a few tough-girl parts at Warner Bros. in the late 1920s, but they didnt fit. As one writer put it, caviar suited her, not corned beef and cabbage. At the peak of her stardom in the late 1930s she once asked her boss at MGM, Louis B. Mayer, for permission to play a scrubwoman character. Mayer forbade it, telling her, You always gotta be a lady.

Next page