Contents

Guide

Page List

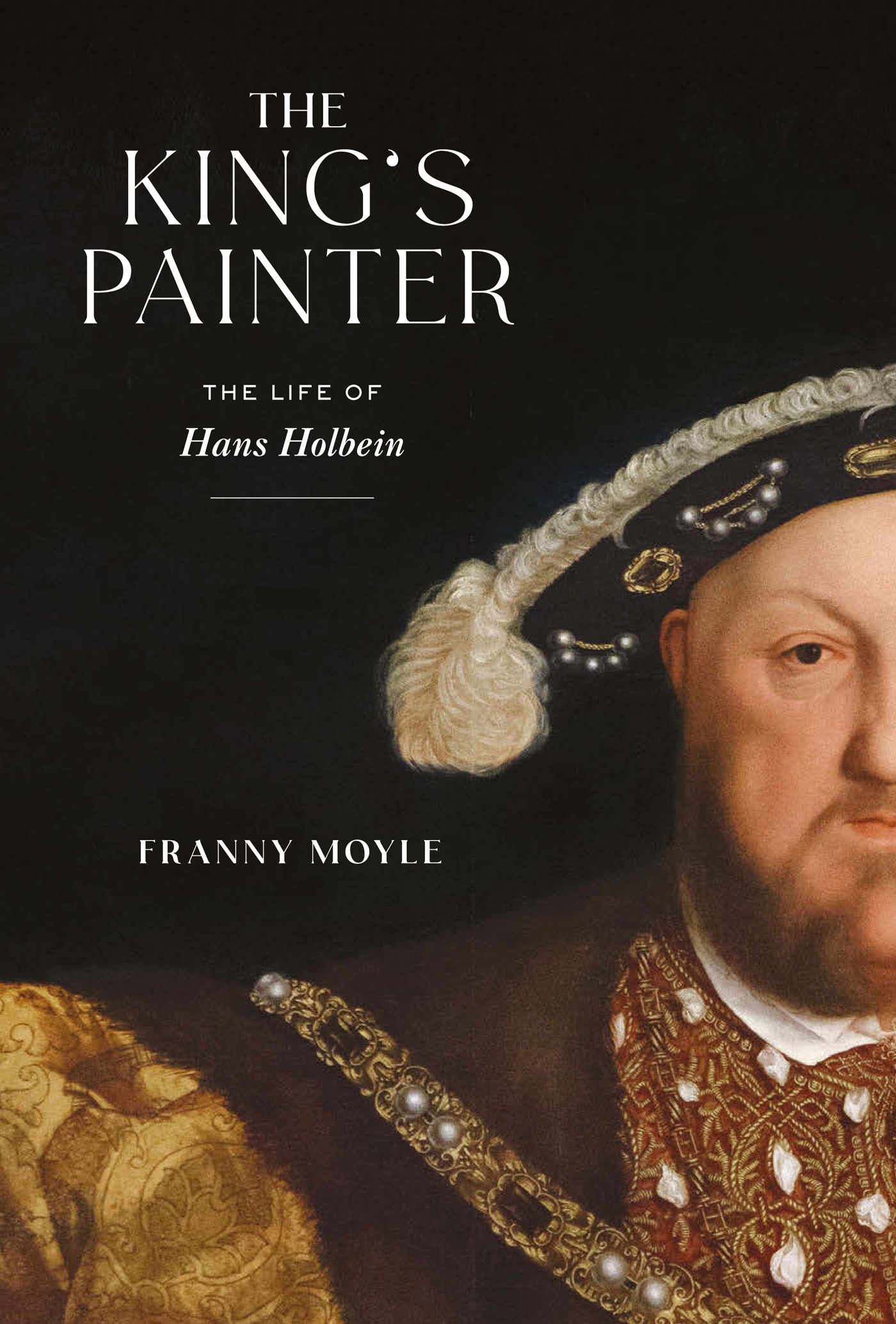

Copyright 2021 Franny Moyle

Cover 2021 Abrams

This edition published in 2021 by Abrams Press, an imprint of ABRAMS.

All rights reserved. No portion of this book may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means, mechanical, electronic, photocopying, recording, or otherwise, without written permission from the publisher.

First published in the UK in 2021 by Head of Zeus

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021934975

ISBN: 978-1-4197-4953-7

eISBN: 978-1-64700-521-4

Abrams books are available at special discounts when purchased in quantity for premiums and promotions as well as fundraising or educational use. Special editions can also be created to specification. For details, contact specialsales@abramsbooks.com or the address below.

Abrams Press is a registered trademark of Harry N. Abrams, Inc.

ABRAMS The Art of Books

195 Broadway, New York, NY 10007

abramsbooks.com

I lost two dear friends shortly after finishing this book, in the dark December of 2020. One, Stephanie Theobald, a fine artist, was in the midst of reading the manuscript for me when she died. The other, gallerist, lithographer and collector Pierre Chave, was a lifelong friend who helped shape my tastes and encouraged my enthusiasms. Both were an inspiration to me. It seems only appropriate that this book should be dedicated to them, though I am profoundly sad they they will never see this message of love and gratitude.

CONTENTS

PREFACE

When Samuel Johnson published his Dictionary of the English Language in 1755, more than two hundred years after Holbeins death, he understood a biographer to be A writer of lives; a relator not of the history of nations, but of the actions of particular persons. Though I am reluctant to challenge Johnson on many things, in this instance it is necessary to point out how very limiting this definition is. A life and the times in which it is lived are inexorably linked. In Holbeins case, the history of nations could not be more relevant to his life. The political and religious turmoil of his era had such a profound effect on the course of Holbeins career that it would be impossible to offer an account of one without the other. After all, this is a man who lived through arguably the greatest upheaval in European history the moment when Catholicism, a religion that had defined Europe and dictated the daily lives and material environment of generations suddenly found itself at war with radical new thinking in the form of what would become called Protestantism.

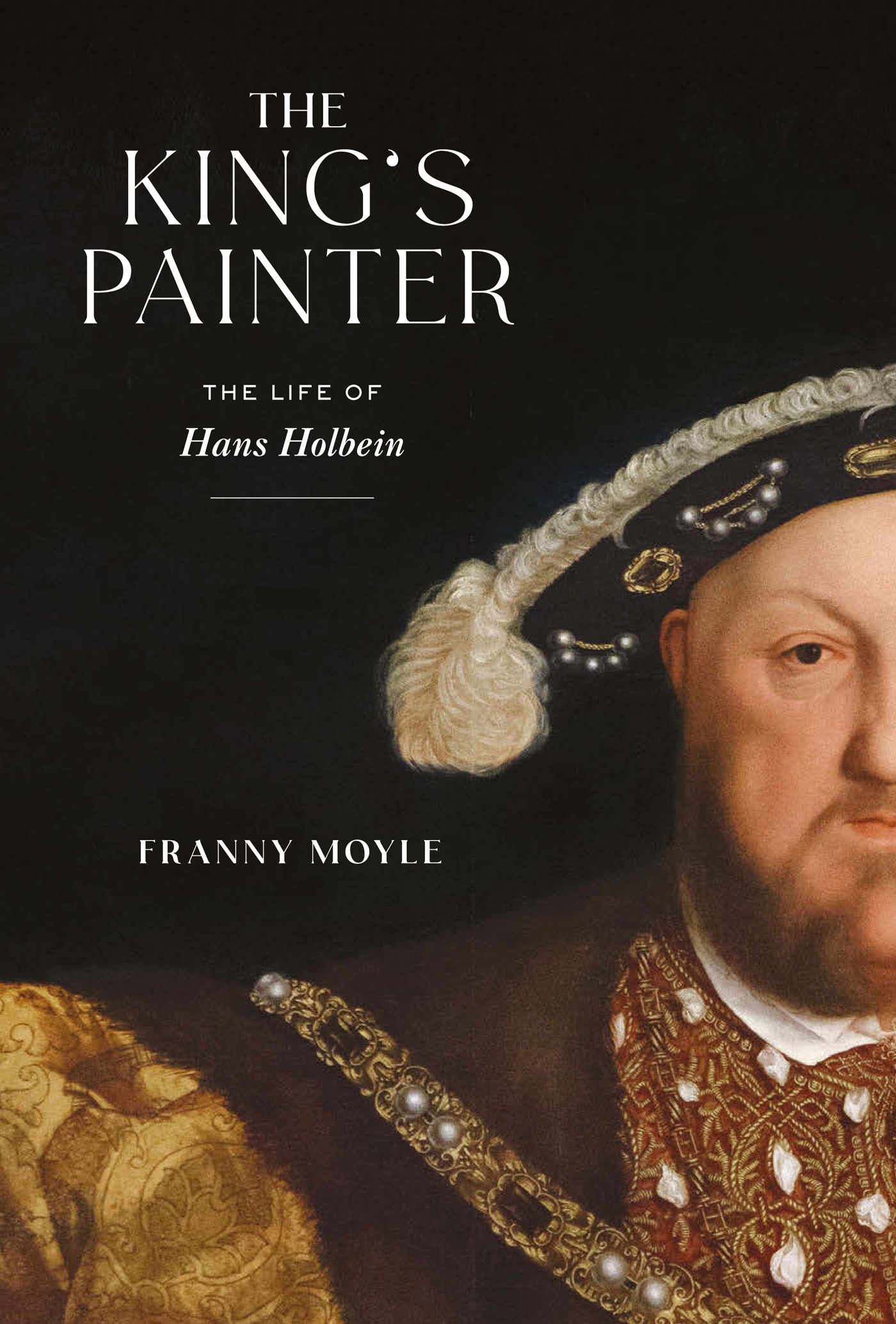

If that sounds rather dry, the consequences on the ground were dramatic. The Reformation that spread across Northern Europe would chase a young Holbein from his hometown of Basel in Switzerland, the sound of the iconoclast mob ringing in his ears, to seek fame and fortune in a London he hoped, like Dick Whittington, would be paved with gold. In a case that could be seen as leaping from the frying pan straight into the fire, he found himself then at the heart of the Tudor court just at the moment that Henry VIII hurled his own country into a period of religious and political uncertainty, and adopted the mantle of the cruel tyrant that would ultimately define his reign, and threaten Holbeins own personal safety.

What is truly astonishing about viewing history through Holbeins story is his proximity to events. This is not a man watching from the sidelines, but a painter who, through a mixture of luck and determination, observed the most extraordinary events of his century up close. Here was someone whose profession, reputation and ambition secured him access to the most powerful men and women of his times. A name that continues to resonate today is Erasmus, a man whose pen was on fire, whose intellect was sought by kings and popes and whom Holbein embodied in a series of images that have described the scholar ever since. But the legacy of Holbeins portraits of the Dutch writer pale when compared to his record of the sixteenth-century English court. Take the most recognized names of the Henrician moment and Holbein likely had a direct and proximate relationship with them: Henry VIII, Thomas More, Thomas Cromwell, Jane Seymour, and Anne of Cleves are but a few. His portraits of these people have become definitive. It is almost impossible to imagine Henry VIII and his entourage through anyone elses eyes but Holbeins.

Holbeins repertoire is wide. Beyond the monarch and his immediate circle, he captured some of the greatest poets in England such as Thomas Wyatt; persecuted martyrs such as Bishop Fisher; the women making new strides for their sex such as Margaret Roper; and the foreign ambassadors who strode the corridors of Henrys palaces. Through his work we see a host of courtiers and their families as they rise and fall in favour, and we glimpse the power of merchants, the discoveries of astronomers, and the rise of lawyers. Holbein gives us a snapshot not just of Tudor royalty but of the socio-economic web woven around it. He immerses us in a lost world. In short, his work describes the Tudor period like no other, and we continue to see it through his eyes.

The question I am most often asked when I mention I am working on a biography is whether there are armfuls of letters, or a diary to draw on. While researching Holbeins life my inevitable reply was very much in the negative. Anyone taking on Holbein as a subject has to deal with the fact that primary written material relating to the artist is sparse, to say the least. Contemporary records are restricted to administrative documents held in the archives in Augsburg where he was born, in Basel where he lived as a young man, and in England where he worked for the last decade of his life. He is mentioned in other peoples letters, and in poetry. His earliest biographer, Carel van Mander, scooped up as much anecdote as he could. But if Holbein ever put pen to paper other than to draw and surely he did his correspondence has long been lost.

The story of his life then is inevitably informed by a degree of detective work. At the heart of this are his paintings, drawings, prints and designs. Where written records are lacking, this visual material that Holbein has left adds up to a chronicle as vivid as any journal. Through his work for the citizens of Basel, his references to the wonders seen in the palaces of the Loire belonging to Francis I and of course his output in London, one plots his trajectory across sixteenth-century Europe. The allusions in his paintings and printed work to the debates of his time speak not only of the vivacious intellectual climate in which he lived, but of his own part in the cultural conversation of his time. His fascination with the science of his era is expressed through his own experiments in perspective and illusion.

The humanity expressed in the faces of those he observes tells us of a man capable of deep feeling. His enchantment with his young wife is clear in his drawing of her; two delightful miniatures of young boys made at the end of his life reveal the sentiments of a man who had fathered at least six children; the haughty demeanour of certain courtiers reminds us that Holbein, even at his most diplomatic, sometimes left his own comment for posterity.