Contents

Franny Moyle

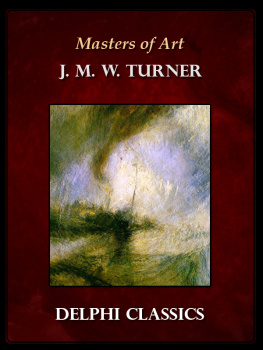

TURNER

The Extraordinary Life and Momentous Times of J. M. W. Turner

VIKING

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

India | New Zealand | South Africa

Viking is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published 2016

Copyright Franny Moyle, 2016

The moral right of the author has been asserted

ISBN: 978-0-241-96455-2

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinUKbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Listen to Penguin at SoundCloud.com/penguin-books

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

To my darling family, Rosa,

Tommy, Vincent and Richard

List of illustrations

Illustration acknowledgements

National Portrait Gallery, London,

Tate London, 2015,

The Royal Academy of Arts, London,

Indianapolis Museum of Art,

Royal College of Physicians, London,

Bridgeman Art Library,

Turners House Trust,

National Maritime Museum Greenwich, London. Greenwich Hospital Collection,

The Collection of Nick Tapley,

The National Gallery, London,

The Collection of Mrs Diana Coker,

1

Admiral Booth

A wet, wintry day in mid-December 1851. The man from Mrs Foords frame-makers stood in the rain and knocked on the door of 47 Queen Anne Street in Marylebone, the professional address of the most famous living British artist, J. M. W. Turner RA. Foords man had work to do there.

Turners Den, as it had become known, looked more like the premises of a painter long dead than the workplace of a living legend. The quiet classical frontage, which once sat respectably alongside the streets other examples of Georgian restraint, had been let go. The windows were filthy, their cracked panes patched with paper. The paint on the front door had blistered and the iron palisades were rusty.

A short hag of a woman answered the frame-makers knock. Her large head was draped with a piece of flannel, striving to conceal a nasty skin affliction. This was Hannah Danby, Turners long-time housekeeper. She led Foords man into a square vestibule barely illuminated by the neglected arched windows to either side of the door, which had become caked with dust. The hall was an empty brown space, bereft of ornament.

As he followed Danby upstairs, the gothic adventure continued. The tradesman was led into the top-lit custom-made gallery where Turners paintings were displayed. The rain was flooding in by the skylight, Foords man would later remember. Turner would not pay for plaster so they had to put paper as well as they could several pictures damaged.

Foords man saw nothing of Turner himself the day he worked in his rain-soaked gallery. This was not unusual. The old painter had become increasingly retiring in his dotage, and over the last twelve months or so had even begun absenting himself from his business engagements at the Royal Academy.

For Hannah Danby, however, it was less her masters absence from his professional commitments that was of concern. It was his absence from his own home that was causing her considerable anxiety in December 1851. The seventy-six-year-old Turner had not set foot in Queen Anne Street since June. This was not entirely out of character for a man who for the last five years had, clearly, been keeping a second home, and from whom she was used to receiving instructions via the postboy. But as Christmas approached, Hannah Danby was beginning to fret. She did not know exactly where her masters second home was, and she sensed something was wrong. She began to search for anything that might suggest its location. A letter discovered in a coat pocket with a Chelsea address was what she needed.

And so on 16 December Hannah Danby sought out a friend, probably Maria Tanner, the woman who assisted her in the care, such as it was, of Queen Anne Street, and the two of them headed south to Chelsea. They found themselves on the stinking Cremorne New Road, a small lane along the Thames that ran from the old wooden Battersea Bridge to the Cremorne Jetty, where penny fares brought revellers by steamboat to the Pleasure Gardens of the same name.

Skirting a muddy foreshore, smelling of the open drains that spilled into the river and peppered with dogs and chickens picking their way through the flotsam and jetsam of the river, Cremorne New Road presented a sharp contrast to the grandiose streets of the West End. Nevertheless, here, facing the timber yards and chemical works of Battersea, was a row of cottages that made up Davis Place. And at No. 6, between Alexander the boat builder and a couple of beer sellers, she found a modest yellow brick house, dating from the 1750s.

Despite the seedy location, it was charming enough in its own way a three-storey, mid-terrace house, fronted by a low wooden picket fence and gate that contained a cottage garden, it betrayed the personal touches of domesticity that accompany a lengthy tenancy. A wooden lattice porch over the front door housed potted plants and a caged starling. The propertys three front-facing windows all had lovingly planted window-boxes, and creepers had been allowed to grow up from one of them and crawl over the uppermost reaches of the faade. But most significantly, in contrast to the neighbouring houses, No. 6 had been customized, at no little expense, to accommodate a high-level balcony or viewing platform, which, cut into the roof and contained by wrought-iron rails, offered an artist a birds-eye view of Londons river stretching out below.

But Turner was not on his platform the day Danby called. And though she quickly ascertained from neighbours that a man fitting her masters description was at home, she also discovered from the hushed tones and shaken heads that they believed he was dying. On hearing this news, Hannah could not bring herself to go in. Instead, distraught, she determined to seek the assistance of Turners cousin and solicitor, Henry Harpur.

Henry Harpur lived in Lambeth. He was seventeen years his cousins junior. The Harpurs and the Turners were strongly entwined. They shared not just blood, but plenty of family business, not least the final revisions Turner made to his will. They had also travelled together on the Continent. On 17 December he visited Chelsea at Hannah Danbys request.