This book wouldnt have gotten written without the urging of my friend Rob Couhig, an attorney here in New Orleans who heard some of my baseball stories and stayed on me to write them down. And then, theres John Stinson, who worked with me in the beginning and whose fringy lifestyle belies a love and facility with words and language. Most critical was Jamie Malinowski, found for me by my able agent, David McCormick. It was Jamie who managed to see a book in the pile of writing I dumped on him. My publisher, Tom Dunne, and my editor, Stephen S. Power, paid me the highest of compliments when they bought into my quixotic journey as an author, while assistant editor Janine Barlow made sure the road was clear and easily traveled. Lastly, I cant appreciate enough the books copy editor, Fred Chase, and its production editor, Ken Silver, who, like my mom, patiently and carefully cleaned up all my spills and put the furniture back where it belonged. And of course none of this would have been possible without my 69 Mets teammates and in particular their wives and former wives who shared their poignant memories of that season, some for the first time.

My thanks to all.

Its a cool late afternoon in New York in mid-October of 1969. In the gloaming, a bunting-covered Shea Stadium, alive with the pulse of a capacity crowd, is draped in long shadows that mute colors and sharpen the edges between light and dark, success and failure. Im in right field, in the only World Series I will ever see from the inside. My overachieving New York Mets, perennial laughingstocks of the National Pastime, lead the rightly favored Baltimore Orioles two games to one, and we are nursing a onenothing lead in the top of the ninth inning of Game Four. Our right-handed ace George Thomas SeaverTom Terrific, The Franchisehas been moving through the Orioles batting order as unstoppably as the earth around the sun, all part of his inexorable journey to the Hall of Fame. Three seasons in the pros, hes already accumulated 57 career wins, and a Cy Young Award is about to elbow its way onto his mantel. But at this moment, after eight innings of excellence, he is in trouble. With one out, back-to-back base hits by Frank Robinson, the Os future Hall of Fame outfielder and two-time MVP, and Boog Powell, their slugging first baseman, have put runners at first and third. Brooks Robinson, the Os shoo-in Hall of Fame third baseman, is at the plate. Our manager, Gil Hodges, who starred at first base for the Brooklyn Dodgers in the 1950s and who played in seven World Series, more than anybody in either dugout, has one of the most able brains in baseball. In this pregnant moment, the tall, lean Indianan, his royal blue warmup jacket buttoned to the neck, takes a slow walk to the mound to make sure the infielders and everyone else are on the same page. He has our top relievers, Ron Taylor and Tug McGraw, warming in the bullpen. Today a manager in this predicament would almost certainly bring one of them in to close the game. (Hell, today a manager would never be in Gils predicament, because a closer would have started the inning, and Seaver would be in the dugout cheering him on.) But in that long-gone era, an elite pitcher like Seaver is expected to finish at least half his starts. Tom is our leader, the best we have, our rock. He isnt coming out.

What had to be dawning on most folks watching was that this game and this World Series had reached its tipping point. If the Orioles seized this moment, they would tie the Series and recapture the momentum; they would have come from behind to beat Seaver at his best, and they would play two of the next three in their home park. On the other hand, if we stopped the rally and won the game, we would be holding a 31 lead with a chance to wrap it up at home. And at that time, only three teams in baseballs lengthy history had come back to win after a 31 disadvantage.

For the players, our families, and the fans, all our dreams were teetering on the fulcrum of this delicious moment. If things fall the right way, youve taken a giant leap toward a gold ring and a place in history. Things go badly and you join the long list of forgettable also-rans. We had a pair of great broadcasters working the series in NBCs Curt Gowdy and, from the Mets broadcast team, Lindsey Nelson. Like all of us, they had to know that the universe of possibility was presenting them with situations worthy of their kinetic art, the ability both possessed to create beautiful word pictures that seem to paint themselves. What an extraordinary place to be for us players, frightening and fun at the same time, our focus honed sharp, ready to engrave a neural etching that we will, each of us, take to our graves.

In right field, I was ready. Id worked hard teaching myself to get a good jump. Eddie Yost, our third base coach, was a wizard with a fungo batthe long, light bat used in fielding drills. He would get me on the end of it, about 150 feet away, and hit me thousands of balls of all kinds, hard grounders and line drives, balls in front of me, balls over my head, to the left and right. The point of the drill was to help me make tough reads and tough plays, in the moment, with gamelike speed. I wasnt just practicing catching the ball; I was practicing seeing the ball right off the bat. Nothing will make you a better outfielder.

With the tying run at third, Im thinking that if the ball is hard hit, Im comfortable going back for it; but if the ball is softly hit, I will want to be in position to try and throw the runner out at the plate, so it might be better for me to move in a couple steps. In the batters box, Brooksie has to be hunting fastball. Seaver featured mostly hard stuff, including a four-seam heater in the upper 90s, a two-seamer with hard run in on a right-handed hitter (which Robinson was), and a hard slider. Such was Seavers command that the venerable manager Gene Mauch liked to say, He could throw it into a teacup. Wherever Seaver decided to throw the ball, it would go there.

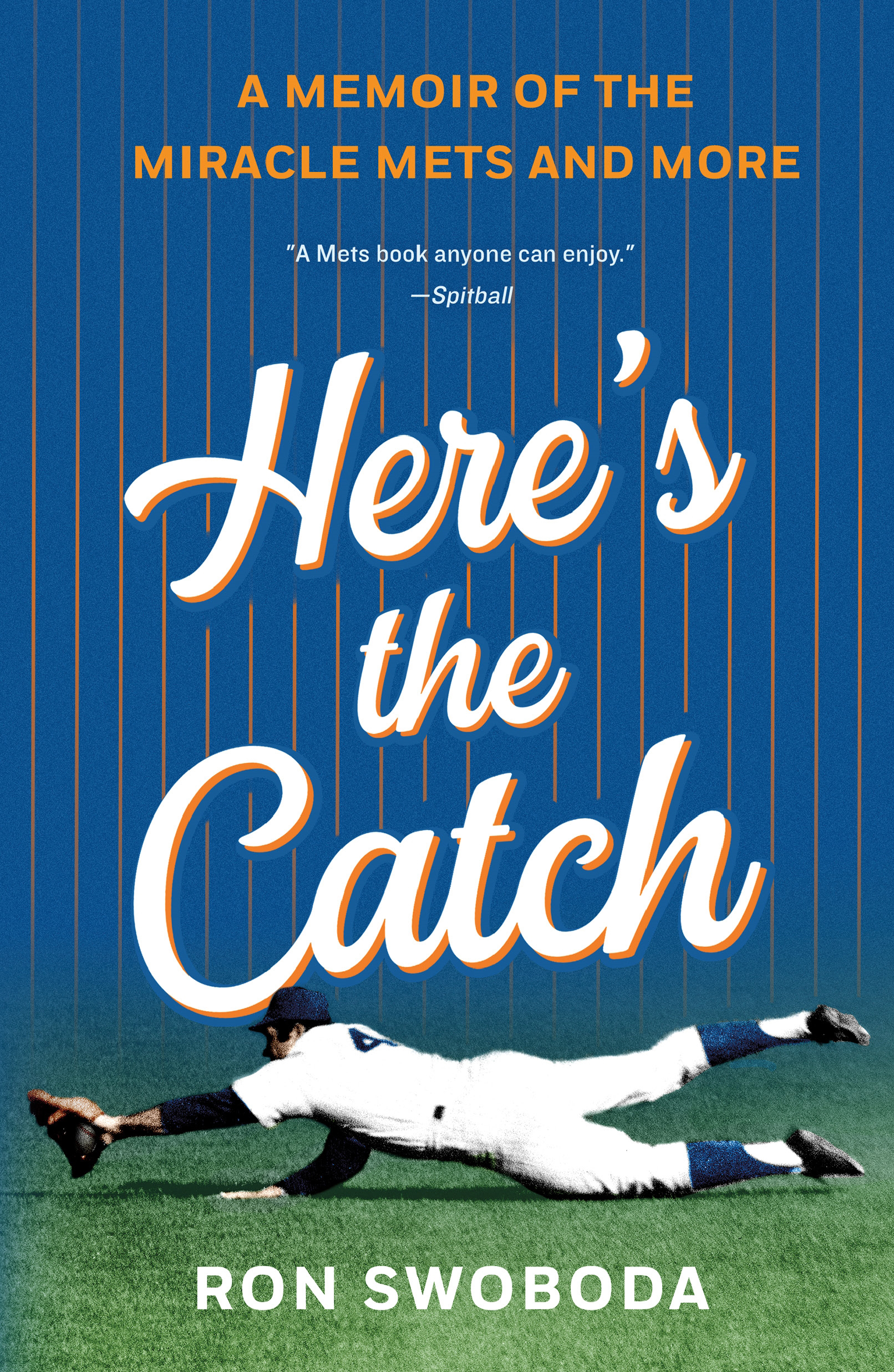

Watching the replay on YouTubesomething utterly unfathomable in the momentit looks like Seaver, pitching from the stretch, goes with his two-seamer down and away, hoping to induce a ground ball and maybe even an inning-ending double play. In which case, game over, we win. But Brooksie squares it up, and lines the pitch sharply toward short right center field.

I had made some incredibly embarrassing mistakes when I first came to the big leagues. I committed 11 errors as an outfielder in my rookie season, second worst in the leaguewhat we call taking the routine out of a routine fly ball. In 1968, I made sixbetter, but still good for the lead among National League right fielders. When the ball is hit to someone who makes that many errors, everyone holds their breath, expecting an adventure. Exacerbating the problem was Shea Stadium, which stood three tiers tall, like a gigantic Globe Theatre. Instead of sky, most fly balls, plus all the liners and little loopers, had the grandstands as a background. With fans there in constant motion, I often felt like I was staring into an ebbing, flowing Jackson Pollock painting, amping up my indecisiveness, which is my fatal flaw, to an almost Shakespearean dimension. Years later, I saw Monets paintings from the Marmottan Museum in Paris, and I couldnt help but wonder what Monet would have seen had he ever stood in right field at Shea and looked into that mercurial autumn light falling on the shouting, shifting fans.