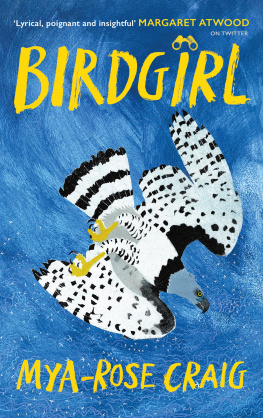

Mya-Rose Craig

BIRDGIRL

A Young Environmentalist Looks to the Skies in Search of a Better Future

VINTAGE

UK | USA | Canada | Ireland | Australia

New Zealand | India | South Africa

Vintage is part of the Penguin Random House group of companies whose addresses can be found at global.penguinrandomhouse.com.

First published by Jonathan Cape in 2022

Copyright Dr MC Birdgirl Limited 2022

Artwork Mick Manning 2022

The moral right of the author has been asserted

Cover illustration Mick Manning

Cover Design Suzanne Dean

Hand lettering Anneka Sandher

Author photograph Mac Breeden

ISBN: 978-1-473-58994-0

This ebook is copyright material and must not be copied, reproduced, transferred, distributed, leased, licensed or publicly performed or used in any way except as specifically permitted in writing by the publishers, as allowed under the terms and conditions under which it was purchased or as strictly permitted by applicable copyright law. Any unauthorized distribution or use of this text may be a direct infringement of the authors and publishers rights and those responsible may be liable in law accordingly.

To Mum & Dad

Without whom none of this would have been possible

Introduction

I dont remember when I became obsessed with birds; it seems to me like Ive been birding for ever. Given that my parents took me on my first twitch at nine days old, its easy to see why I might feel that way. The towering bookshelves of our house are filled with titles such as Shrikes, Sunbirds, Woodpeckers and Nightjars, beautifully illustrated guides to the birds of every corner of the world. As a child, and before I could even read, I would heave these books on to my lap to pore over the illustrations, tracing them with my fingertips, imagining I was stroking the soft feathers of a hummingbird, glimpsing a pitta in a shady rainforest or basking in the reflected rays of the Regent Bowerbirds golden plumage. Later, I would copy the drawings into my own notebooks, while planning extensive birding tours that would take my family all over the world.

By the time I was born, Mum, Dad and my older sister, Ayesha, were already a well-known birding family, young and cool among the waterproof-clad, middle-aged, White male archetypes who made up the community at the time. Mum stood out from the crowd in other ways, too she is Sylheti Bangladeshi and the birding circle wasnt known for its ethnic diversity. We were quirky enough to be featured on a 2010 BBC documentary, Twitchers: A Very British Obsession.

Birds took me out into the British countryside and then beyond, travelling the seven continents with my parents, where I was exposed not only to rare, endemic and magnificent new birds, but also to the impact of habitat degradation on people and wildlife. I witnessed biodiversity loss due to climate change, logging and palm oil plantations, as well as other overexploitation of the land.

Becoming a political and environmental activist felt like a natural progression, and one of my first steps into activism was inspired, unsurprisingly, by a bird: the tiny Spoon-billed Sandpiper, whose numbers were falling dramatically due to loss of habitat on its breeding grounds in Siberia. Global warming was an issue, as was human destruction of mudflats in China and South Korea where the birds break to feed during their migration south. Trapping, too, was a big problem for the Sandpiper, a disastrous bycatch alongside the larger waders hunted for food by people scratching a living on the birds wintering grounds in Myanmar and Southern Bangladesh. This was, very simply, a microcosm of the environmental issues facing the world.

In the summer of 2011, the global population of 200 Sandpipers weighed less than a single swan. Without human intervention, scientists believed it was highly likely that the species would become extinct within ten years. As part of a desperate effort to create a backup population an ark, so to speak conservationists transported thirteen young Sandpipers from the Siberian tundra to Slimbridge Wetland Centre in Gloucestershire, only an hour from my home near Bristol. The captive population was added to the following year, when fourteen eggs were brought back from Russia and successfully hatched at Slimbridge. I remember hearing the news; it was an extraordinary and poignant moment, demonstrating what can be achieved when global conservation organisations work together.

The knowledge gained from creating this captive population led to a development called head-starting. Conservationists collected, incubated and hatched the eggs on their breeding grounds and then hand-reared the chicks ready for their safe release. This process helped increase the number of fledglings that survive each year by 20 per cent, and since 2015, 180 Sandpipers have been released back into the wild. Today the population is estimated to be around 1,000 birds.

In 2015, I was lucky enough to visit Sonadia Island in Bangladesh as part of the international task force to make a count of the migratory population. Every winter the Sandpiper departs its remote breeding grounds in far north-eastern Russia to undertake an 8,000-kilometre migration travelling along the coasts of Russia, China, South Korea, down to Myanmar and Bangladesh. Just fourteen centimetres long, its comical spoon-shaped bill is very much part of its unique identity, and the tool it uses to sift through mud and silt, in pools on beaches, mudflats, and other shallow wetland areas, in its search for small invertebrates to feast upon.

As Mum and I boarded a motorboat to sail out to Sonadia Islands mudflats to begin counting, we had only one question on our minds: were these winter visitors increasing or reducing in numbers? It was a hot day and a heat shimmer lay over the land. Was that a Sandpiper in the distance? Yes! There was its weird bill, its fluffy white underbelly and speckled brown and grey wings. It was strange to see the bird in the flesh and feathers, knowing it had successfully made its epic trip.

This was a project I could get behind. The year before I had launched my blog, Birdgirl, where I featured the many birds I had seen from around the world; now I added the Sandpipers plight to my pages and in Dhaka I was able to use my growing social media platform to publicise the plight of the Sandpiper through TV and national newspapers within Bangladesh as well as to the Bangladeshi diaspora in the UK. I was launched on a lifelong campaign to highlight the impact of climate breakdown and human destruction on our natural environment, on birds, on the land, and on people.

Birds serve as a kind of canary in the coalmine for climate change. The international effort for the Spoon-billed Sandpiper becomes all the more poignant when you imagine that the predicted one-metre rise in sea level would not only submerge Sonadia Island but also almost 20 per cent of Bangladesh one of the most densely populated countries in the world by 2050. A disaster for the Sandpiper and humans alike. But if we save the Sandpiper, we will also save all the species of mammals, fish and insect life that share its precarious habitat.

When I was seventeen, in 2020, I was invited to share the stage with the Swedish climate activist Greta Thunberg, at the Bristol Youth Strike 4 Climate rally. I was a long way from the mudflats of Sonadia Island, and over the years, I had honed my message and my approach to activism. While the conservation projects of our birds and wildlife remain priorities for me, in front of an audience of 40,000 I spoke about those without a voice: for Indigenous Peoples removed from their ancestral lands in the name of conservation, for the injustices visited upon the global south in the name of climate change action. I found my own voice as a young teenager and, while the journey feels much longer than the space of a few years, it is a voyage I intend to remain on.