Contents

Guide

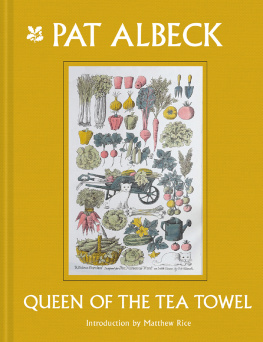

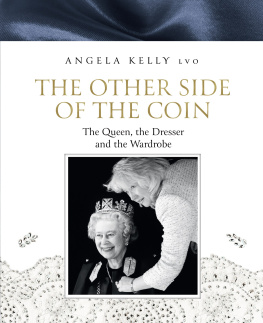

PAT ALBECK

QUEEN OF THE TEA TOWEL

PAT ALBECK

QUEEN OF THE TEA TOWEL

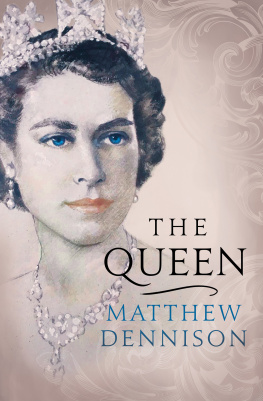

Introduction by Matthew Rice

PATS TEA TOWELS

Just as the programme serves as souvenir of a play, a lasting memory of the visit to the theatre, so, for many years, the tea towel was a vital part of a visit to a National Trust property. Millions of linen cloths were sold in Trust shops nationwide and taken home. Many were pinned or hung on the kitchen wall, a reminder of each of the pieces that make up the richest collection of property ever amassed in the country.

By far the majority of these were designed by one woman whose background as the child of Jewish immigrants from Russian Poland was as far from the patrician ways of the twentieth-century National Trust as could be imagined. Pat was the youngest daughter of Motel Albeck, a furrier. He and his wife Sarah had arrived in Londons East End in 1908 leaving behind their lives and families in the shtetl of Zarimbe near Warsaw. They then moved to Hull, where Pat was born.

Motel, now renamed an anglicised Max, was quickly established in a new business and sent the three eldest daughters to university. However with modest results at School Certificate, Pat was quickly dispatched to the Hull School of Art where she shone. Winning, in 1950, a place at the Royal College of Art, she left for London. There she met her husband, Peter Rice, a painting student, and from then on their lives were utterly devoted to design until their deaths in 2015 and 2017. At the RCA, Pat had studied in the textile school and worked in fashion and furnishing design throughout the 1950s and 60s, but a chance meeting at a dinner added a further dimension to her work.

Pat and Peter had moved from South Kensington (where they had settled while at the RCA) to Chiswick Mall in 1963. In part the product of the intrusive construction of the Great West Road the year before, this ribbon of variegated houses was inadvertently isolated from the rest of grittier west London and became an oasis of Thames-side quiet. It had already been established as an artistic enclave, and foremost amongst its residents at the time were the painters Mary Fedden and Julian Trevelyan. As close neighbours they instantly became friends of Pat and Peter. An introduction to Marys cousin Robin, who was historic buildings officer at the Trust, led to a discussion about the possibility of Pat producing some illustrated dishcloths for the tables. The tables were the low-key predecessors of the later ubiquitous National Trust shops, simply a table in the hall where some postcards were sold along with the property guidebooks. Pat was delighted and there began a fifty-year productive relationship.

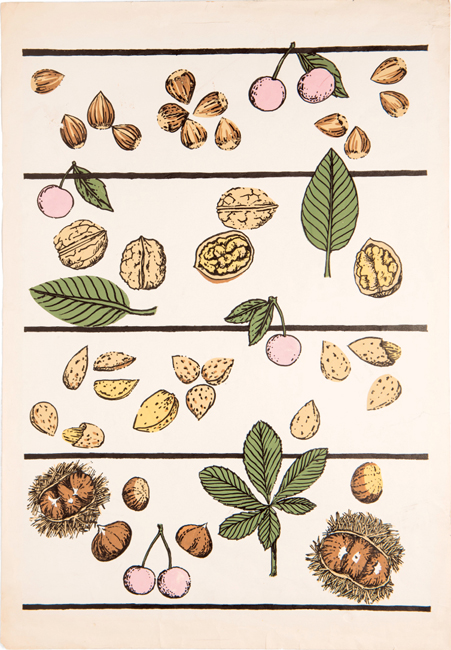

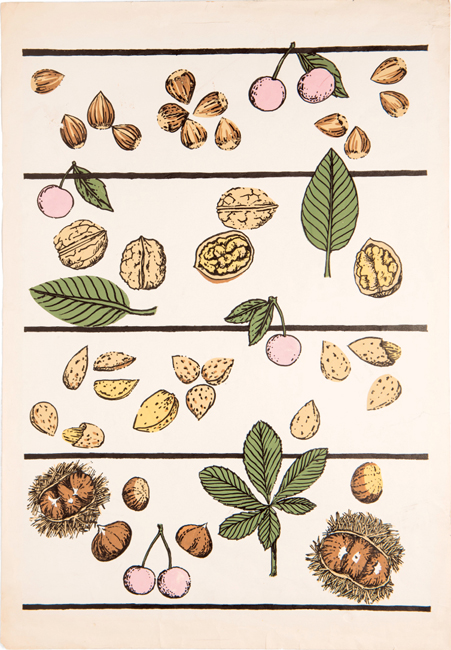

This is the first Pat Albeck tea towel. Bold and graphic, it was produced in 1954.

If the tea towels defined Pat Albeck for many people it was conversely the case that her designs exemplified the extent and the tone of the Trust. Perhaps they even served in some way as a precursor to the more accessible and egalitarian organisation it was having so much difficulty in becoming. Pats combination of informed acute observation and bold schematic design produced a representation of the houses, parks, kitchens and gardens of the Trusts estate that was itself a welcoming and familiar introduction to what had been the privilege of the few.

Pat designed over 300 tea towels for the Trust. This book is a record of that body of work, containing a selection of the designs that have given so much pleasure both to the members of the Trust and to their designer. Pat took her role seriously, with missionary zeal! Every design merited a visit to the place to be depicted, whether in Cornwall, Northumberland or Norfolk... Often in the company of her long-time commissioning editor Ray Hallet, she would inspect the property, working out exactly what constituted, for her, the most characteristic aspects of the place. Perhaps it was this approach that made her own observations chime so clearly with that of the visitors for whom she was designing. The Reformation, the Civil War, the Grand Tour or the Picturesque had little resonance for Pat, however the Industrial Revolution and the Arts and Crafts movement meant rather more to a designer who came of age professionally in the post-Festival of Britain atmosphere of the 1950s when design seemed capable of changing the world.

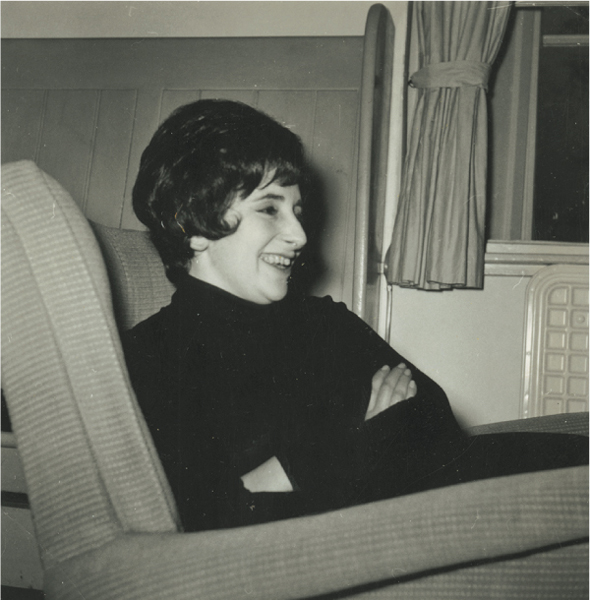

Pat at the Royal College of Art, 1951.

Pats perception of pattern and colour, her passion for gardens more specifically for flowers and her ability to see what was speaking to those who loved the places she illustrated made for a remarkable series of images. Briskly waving aside instructions from bristly, tweedy land agents or indeed former owners that the house is seen at its best from the south-east, Pat would assimilate details and elements that were seen as ancillary and unimportant to many but that proved to be just the telling detail that expressed the character of a place. Set-piece views of course made their appearances but their formality was frequently softened by a decorative border constructed of some more everyday or charming element: carrots, flower pots or teaspoons. Amongst her most popular designs are those that step outside the property-specific: wild flowers, butterflies, even cats of the National Trust became bestsellers and, in due course, collectors items.

Pat would begin with a rough design in miniature for discussion with what often became quite a team of clients but essentially these were to show to Hallet. He performed the essential role of any editor questioning and challenging, even if the design was almost as desired. He was visually sophisticated and knowledgeable, and their conversation stimulated Pat to refine and complete the image. That relationship became one of the most important in her career (as well as an enduring friendship thriving till her death). Pats confident and unfailing line combined powerfully with her strict economy with colour, the most elaborate of her designs relying on five colours and an outline, often using clever overprinting and combinations to give the impression of multi-coloured naturalism. The plates shown here are a mixture of designs in gouache and felt pen on watercolour paper (Kent 90lb NOT) and those actually printed on linen or linen union.

Tea towels are ephemeral, even throwaway. Their most everyday of purposes might seem to rob them of any potential dignity. Frayed and holey, hanging on the rail of the Aga or revisited in a pile of ironing, the faded garden of Sissinghurst or ghostly view of Bodiam Castle reappears in ever diminishing focus. But that very quotidian character also makes them familiar significant even and most importantly, worthy of the profoundly serious way that their decoration was conceived.

Perhaps the strength of these images comes from this contrast; on one hand Pats heritage as the child of immigrants from Central Europe, land of peasant art and of simple repeating patterns in bold colours and on the other, the many-stranded inheritance of the National Trust, whose custodianship of two great pillars of British culture the country house and the man-made landscape represents the very opposite: a complex synergy of high cultural influences.