Contents

Guide

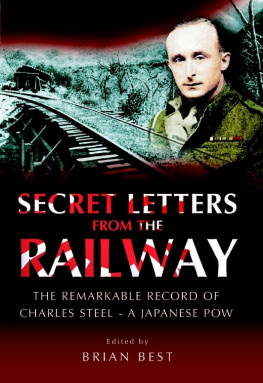

PETER REES has had a long career as a journalist covering federal politics and as an author specialising in Australian military history. His books include Anzac Girls; Desert Boys; Lancaster Men; Bearing Witness: The Remarkable Life of Charles Bean; and The Missing Man: From the Outback to Tarakan, the Powerful Story of Len Waters, Australias First Aboriginal Fighter Pilot.

SUE LANGFORD has been a practising psychologist for more than thirty years, the past twenty of which have been in private practice, working in both clinical and organisational roles. She has provided consultancy services to the Department of Defence and other government agencies over the years. Her particular interest is in trauma management.

To the memory of Scott and Marge Heywood.

Their love endured the worst of times in anticipation

of the best of times.

He who has a why to live can bear almost any how.

Friedrich Nietzsche

Contents

Scott Heywood jealously guarded the paper he scrounged to write letters paper that had to be hidden from guards.

The practice carried with it an inherent risk: if the guards discovered the cache, not only would the letters be destroyed, the punishment would be swift and unforgiving. As the months turned into years, the risk grew with the letters increasing bulk. Even knowing they could not be posted, Scott kept writing.

He was a young Australian soldier who had volunteered to go to war, becoming one among the 13,000 Australians who were forced to work as prisoners of war of the Japanese on the infamous Burma Railway (also referred to as the ThaiBurma Railway) during World War II after the surrender of Singapore. Nearly 2650 Australians died on the railway, 479 of them on the Burma section.

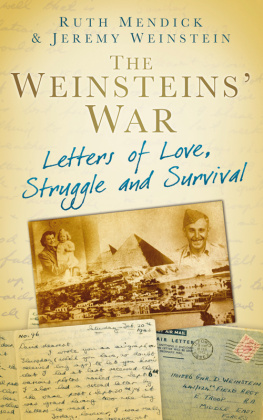

So comprehensive are the 389 letters Scott wrote as a POW (among 570 letters in total) that they form a diary of the war as it played out in Malaya and Singapore, and then of Scotts captivity in Burma. Unintended but powerfully buried in the words is an uplifting and optimistic treatise on how to survive in extreme circumstances. At the same time, they are tender messages of love: hundreds of unsent letters, all addressed to Marge, Scotts young wife, at home nurturing their two young sons in rural Victoria.

Scotts experience of captivity in Burma bears an uncanny resemblance to another story, happening 7000 kilometres away in Europe around the same time. Viktor Frankl, a psychiatrist, was rounded up with his wife and family and sent to the Auschwitz concentration camp in September 1942.

Both Scott Heywood and Viktor Frankl were incarcerated and wrote of their means of surviving, albeit in very different situations. Both had in common the struggle to withstand deprivation and cruelty while living with the ever-present prospect of death. How they did so was uncannily similar.

Scotts story would have been like that of many other POWs, men with similar attributes and strategies that helped inoculate them against the effects of bashings, disease and starvation. And luck, of course, played its hand many times. But what makes Scotts experience unique is that he wrote it down, daily, preserving the immediacy of the moment.

Viktor Frankl told his story in his best-selling book, Mans Search for Meaning. Scott Heywoods story has not been told. Until now.

The news Margery Heywood had longed for leapt out at her from the morning paper. It was 15 September 1945. After years of captivity as prisoners of war, the men of the 8th Division of the Second Australian Imperial Force (AIF) were coming home. A photo of diggers at the Yokohama railway station holding a handmade Australian flag said it all. Under the slouch hats were haggard faces, but now they were wearing broad smiles.

A month before, Japan had surrendered. These men had borne the brutality meted out by their Japanese guards and survived. The ex-POWs were arriving in successive waves every few days and the newspapers picked up on the excitement and were capturing moments of reunion on their front pages.

Milling on the platform at Spencer Street Station in Melbourne, the diggers and their loved ones searched the crowd for a familiar face. Then the instant of recognition and embrace joy mingled with relief. After the dark years of war, this was the moment they had pictured in their minds, over and over. And these were the moments the photographers waited for.

What excited Marge was news that more 8th Division ex-POWs would be following. No definite dates were available, but as her husband, Scott Heywood, was part of the 8th Division, he had to be in one of these arriving groups. She would fling her arms around him, just like those people in the paper.

Marge had not seen Scott since mid-1941; it had been a void filled with anxiety and silence and telegrams. Those ominous, simple slips of paper that signalled the news of a mans life or death. She had been beside herself for so long, fearful of Scotts fate. No news only increased the anxiety, feeding the different scenarios that played out in her mind. She had received the first telegram in October 1943. It broke twenty-one months of silence twenty-one months of not knowing whether Scott was living or dead. The telegram informed her that Scott was alive and a POW in Burma. Her relief was overwhelming and then came more silence. For a year.

A second telegram, in October 1944, finally broke this awful silence, starkly and dispassionately informing her that Scott was missing, feared dead. A Japanese transport ship taking him and hundreds more Australians to Japan had been torpedoed. Six weeks after that blow, Marge had received a further telegram, confirming the news. It began with I regret to inform you... She knew what was coming. It is feared that your husband... lost his life. Scotts records would now be endorsed with a sentence that made Marge shudder: Now reported Missing believed Deceased on or after 12/9/44.

These words, so clinical in their announcement, seemed so final. Scott was missing, but the governments belief was that he was dead. Scott dead! Grief struck. Marge had two small boys who barely knew their father and would now have to face life without him.

It was an agonising three months before Marges world was turned upside down again, when yet another telegram arrived in January 1945. This one began: It is with pleasure that I have to advise you... And she knew what that meant: Scott was alive! Still a POW, but he was alive!

In this topsy-turvy world of war there was relief and joy for Marge and the whole family. There was hope again. She could now contemplate a future. A follow-up telegram bolstered her even more. A Japanese propaganda radio announcer read a short statement from Scott urging her to keep smiling. Marge knew it was from Scott it was just what he would say. This was something to hold on to, in a time of so little news due to the fractured communications of war.