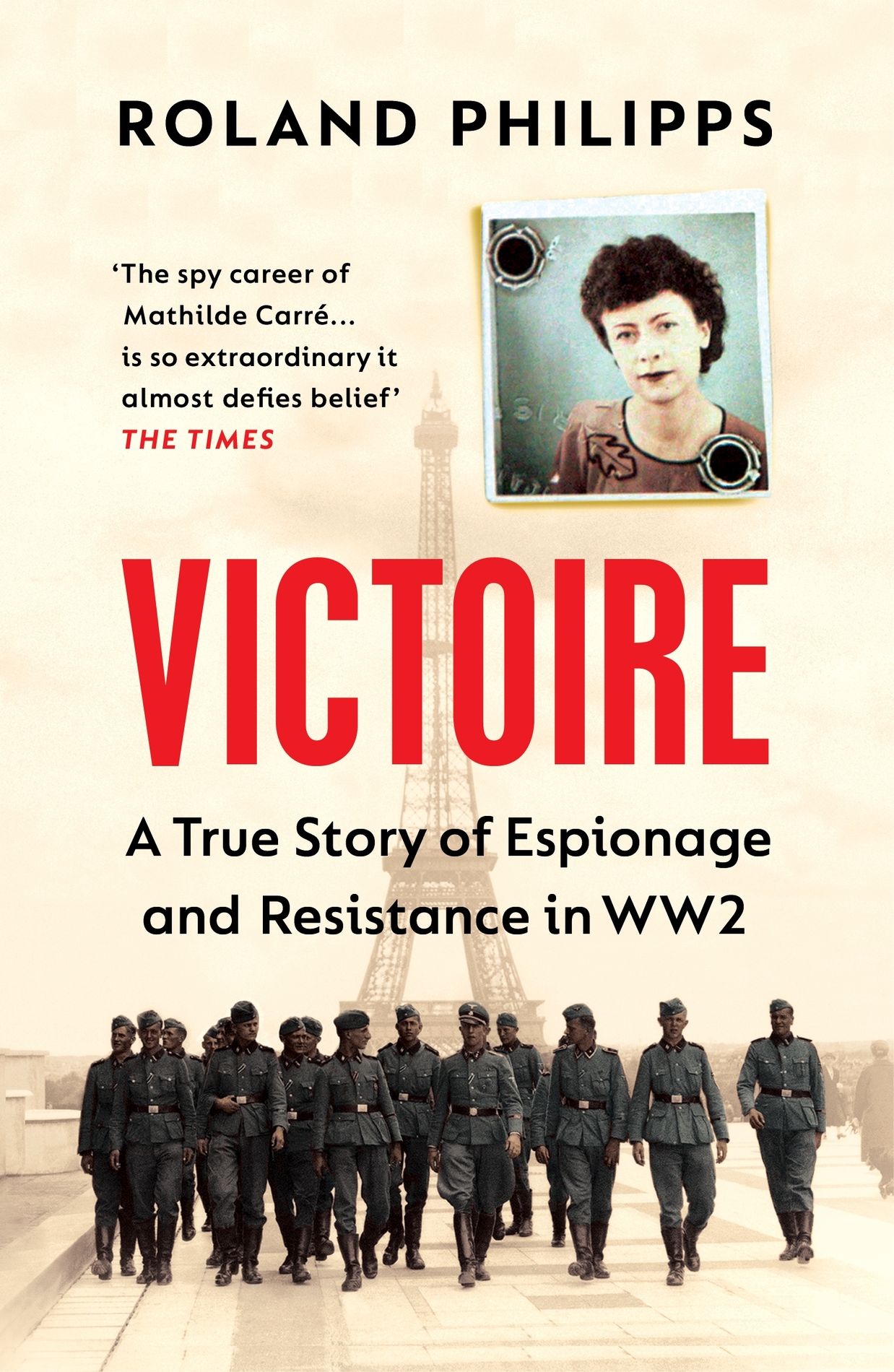

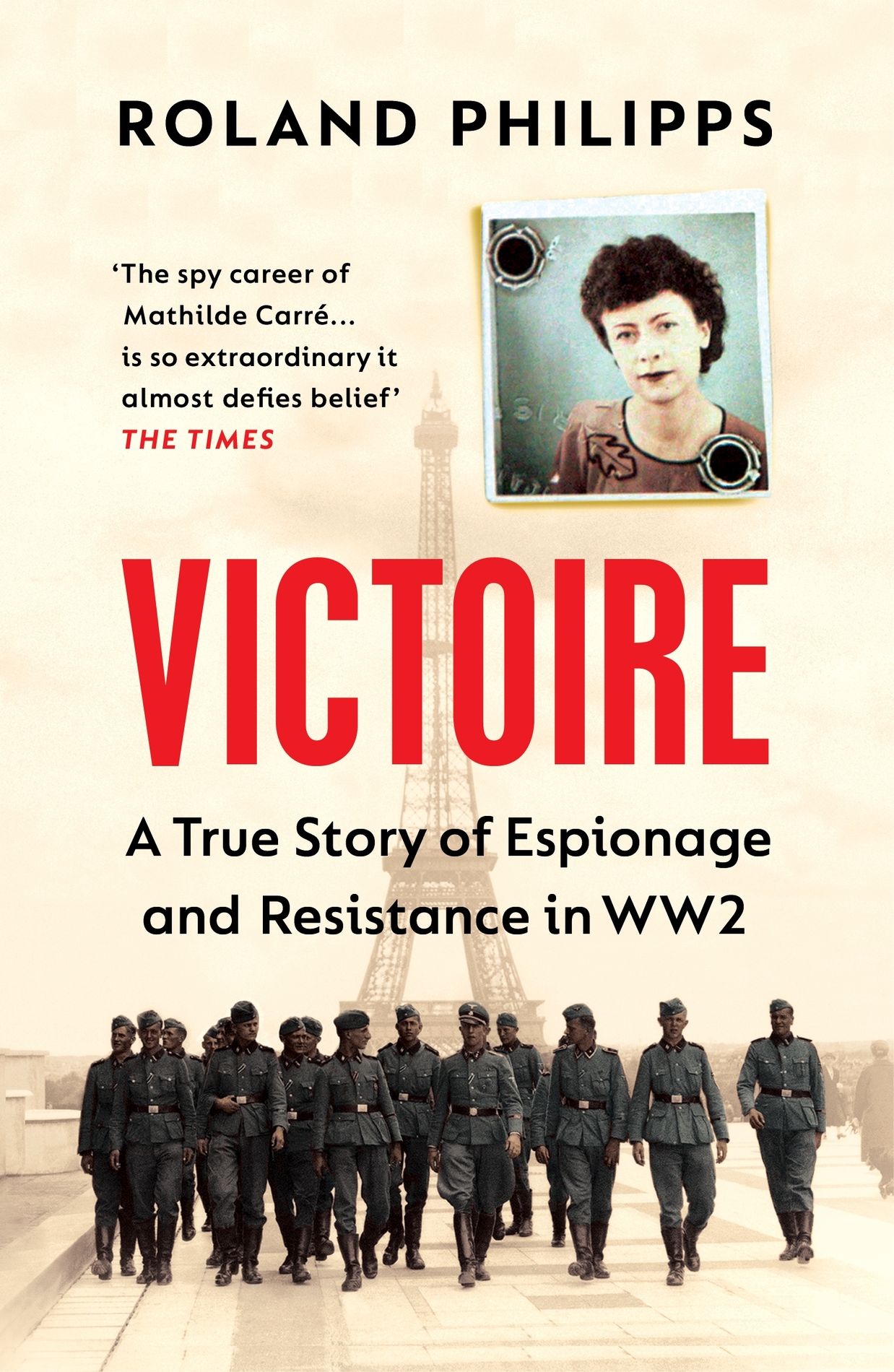

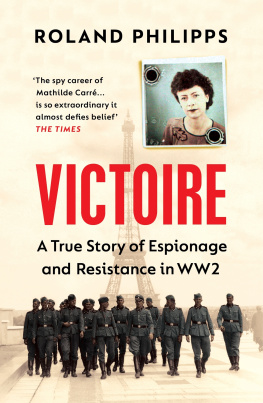

Roland Philipps

VICTOIRE

A Wartime Story of Resistance, Collaboration and Betrayal

Contents

About the Author

Roland Philipps was a leading publisher for many years. His first book, A Spy Named Orphan: The Enigma of Donald Maclean, was published in 2018 to wide acclaim.

Also by Roland Philipps

A Spy Named Orphan: The Enigma of Donald Maclean

For Nat

List of Illustrations

. The factory town of Le Creusot: Collection Dupondt / akg-images.

. Mathilde Belard: I Was The Cat by Mathilde-Lily Carr, Souvenir Press Ltd, 1960.

. Mathilde with husband Maurice Carr: Tallandier / Bridgeman.

. Roman Czerniawski: Archive PL / Alamy Stock Photo.

. Czerniawski with his regiment: Gerry Czerniawski.

. Toulouse: Apic / Getty Images.

. The Champs-Elyses: Sueddeutsche Zeitung Photo / Alamy Stock Photo.

. Lydia Lipski: John Izbicki, The Naked Heroine, Umbria Press London, 2014.

. Monique Deschamps: Gerry Czerniawski.

. Rue Villa Landre: Paul Almasy / akg-images.

. Rene Borni, Agent Violette: The National Archives: Image Ref: KV 2/929 (1).

. Roman Czerniawski: Gerry Czerniawski.

. Hugo Bleicher: The National Archives: Image Ref: KV 2/166.

. Suzanne Laurent: Colonel Henris Story, Edited by Ian Colvin, William Kimber, London, 1954, (photographer unknown).

. Rue des Saules: TopFoto / PA Images.

. La Sant prison: Historic Images / Alamy Stock Photo.

. The Villa Baur: Paul Almasy / akg-images.

. The Cattery: The Cat With Two Faces, by Gordon Young, Putnam London, 1957.

. Pierre de Vomcourt: The National Archives: Image Ref: HS 9/1539/6.

. Carte didentit of Major Ben Cowburn: Imperial War Museum / Documents. 12716 Ref/Cowburn_012716_5.

. Daily Sketch clipping: John Frost Newspapers / Alamy Stock Photo.

. J. C. Masterman: National Portrait Gallery / NPG x90551.

. Tar Robertson: Private Collection.

. Christopher Harmer: Private Collection.

. Susan Barton: Private Collection.

. Headband: Imperial War Museum / EPH 4086.

. Klop von Ustinov: Imperial War Museum / HU 57817.

. Lord Selborne: National Portrait Gallery / NPG x164052.

. Richard Llewellyn Lloyd: National Portrait Gallery / NPG x23601.

. Mathilde trial: AGIP / Bridgeman Images.

. Albert Naud trial: Heckly / AP / Shutterstock.

. Rene Borni in court: AGIP / Bridgeman Images.

. Hugo Bleicher: Keystone Press / Alamy Stock Photo.

. After her release Mathilde Carr: Photo Jean Tesseyre / Paris Match via Getty Images.

. The map on page 47: Gerry Czerniawski.

Prologue

Moulin-de-la-Rive, Brittany

12th/13th February 1942

The sliver of moon gave almost no light as a Lancashire-born engineer, an aristocratic French Resistance leader, a German military intelligence officer and a short figure in a black fur coat converged on a remote, chilly cove on the north-western edge of Hitlers Fortress Europe. They were awaiting the arrival of a Royal Navy boat to hurry all but one of them across the Channel to England.

The three men were brought together by the only woman of the bizarre party. Her coat that had seen better days and the battered red hat on top of its owners cropped dark hair did not suit her code name of Victoire as she stumbled myopically along in the darkness. Mathilde Carrs own war had already been eventful, and her impact on the men accompanying her critical. Her current code name was not her first in the twenty months since her country had been humiliated in its armistice with Germany: for one glorious year she had been known as La Chatte.

Were the stakes not so mortally high, the choice of rendezvous might have smacked of that particularly British trait, an ironic sense of humour. Only hours earlier, the mighty battle cruisers Scharnhorst and Gneisenau, the pride of the Kriegsmarine, had slipped out of the harbour at Brest and steamed up the English Channel past this cove. Such naval effrontery was only possible because signals from The Cattery transmitted to London on Carrs wavelength had indicated that the ships were quite unable to put to sea. So much faith was put in her intelligence-gathering that this was believed even if other accomplished spies on the ground told a different story. An opportunity had been lost for the RAF and the Royal Navy to strike a memorable blow in a low period.

Yet the Cat herself was now being smuggled out of France with the blessing and connivance of the Nazi occupiers of her country, to begin the next stage of a career that remains controversial as questions swirl around her patriotism, honesty and courage.

1

A Profound Need

The dirty, small black factory town of Le Creusot in Burgundy where Mathilde-Lucie Belard was born in 1908 could never have nourished a girl with her ardent imagination. She was an advanced, solitary child, able to both walk and talk at the age of one, and spent her early years in the wholesome mountain air of the Haut-Jura in her grandparents rambling eighteenth-century house with its steeply pitched roof, a paddock and a large garden.

Mathildes father was an engineer in the steel industry that dominated Le Creusot, and so in love with her assertive mother Jeanne that Lily, as Mathilde was known in her family, believed that their amorous intimacy would have disturbed her even as a baby if they had not sent her to live with her maternal grandfather. She would come to look back on herself as a very miniature little lady, and whilst an early lack of parental guidance meant she struggled to parse emotional nuance in herself or read those around her, it instilled a spirited self-determination to try out all that life had to offer.

Her grandfather was an emotionally remote yet tender and indulgent man who slipped Mathilde sugared almonds when she was reprimanded; he was eighty years her senior and shared his house with his spinster daughters, both in their thirties. Aunt Isoline and Aunt Lucie were contrasting and marked influences on their charges developing character. Aunty Tine loved music, a party, stories and clothes, and opened Mathildes mind to the possibility of a life of romance; Aunty Cie, nicknamed the Sad One by her niece, was dutiful, virtuous, and a high-minded substitute for a real mother. Mathilde loved Lucies balanced calm but would share her periodic fits of depression, during which Lucie wrote poems she never dared to offer for publication. One of these involved a stream which Mathilde was told represented devotion, patriotism and sacrifice:

In that desert which is my life

There flows a charming brook,

Fragrant with honey and nectar

In which I have drowned many a regret

The poem implanted a desire in Mathilde, at all costs, to die as a martyr for France, as she was to recall at a time when she was puzzling out the arc of her life. It was the first encapsulation of her romantic sense of her destiny, whose echo was to return to her twenty-six years later at a moment of devastating crisis to rally her innate heroism.

Her earliest memory was of weariness, cold sweat and a feeling of nausea. She was undergoing scarlet fever, and on her recovery was fed a baked apple, the taste of which would instil childish joy for the rest of her life; she could never drink champagne, given as medicine, without bringing her sickness to mind. She could not understand why the bells tolling wildly at the start of the war in 1914 caused her aunts to be so tearful, and was unsure how to behave: all she could think to do was continue with her household duties of making her grandfathers bed and helping with meals. The skill that would be useful to her in the next war of how to live with secrets whilst putting on a front of normality was being imprinted early.

Next page

![MATHILDE Fibiger - Et Besøg. Nye Breve af Forfatterinden til Clara Raphael (Mathilde [Fibiger])](/uploads/posts/book/218524/thumbs/mathilde-fibiger-et-bes-g-nye-breve-af.jpg)