CHAPTER ONE

THE WORLD BEFORE THE GS (19751979)

It is easy to assume that the creation of the first BMW G/S was some kind of inspired work of genius globe-changing events or creations do not just happen after all. In the car world, the talents of a select group of designers are duly applauded: Ferdinand Porsche for the VW Beetle; Alec Issigonis for the mould-breaking Mini; Colin Chapman at Lotus. The motorcycling world reveres Edward Turner for the Triumph Bonneville, Tadao Baba for the Honda FireBlade and Massimo Tamburini for Ducatis 916. But the BMW G/S had no true father figure; there was no genius creative force behind it. In fact, there was no clear act of inspiration at all. Instead, it was more a result of desperation, tinged, as BMW today will readily admit, with more than a little luck.

It is also natural to think that the eventual unveiling of that first GS, the R80G/S, in 1979 must have been some kind of epiphany. Surely the bike that was not only to spawn a whole BMW dynasty but also to inspire a completely new motorcycling genre one that instantly proved a best-seller and over the next thirty years would go on to become not just BMWs bread and butter but the whole embodiment of the brand was welcomed to universal acclaim? It was not. Instead, the R80G/S was viewed as something of an oddball, launched in a somewhat sheepish fashion, with little fanfare. It was initially dismissed by many as a curiosity with minimal appeal, as is often the way with game-changing machines: it caught everyone by surprise.

THE RISE OF THE TRAILIE

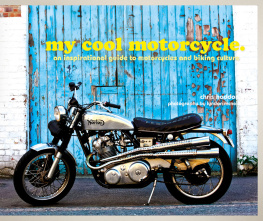

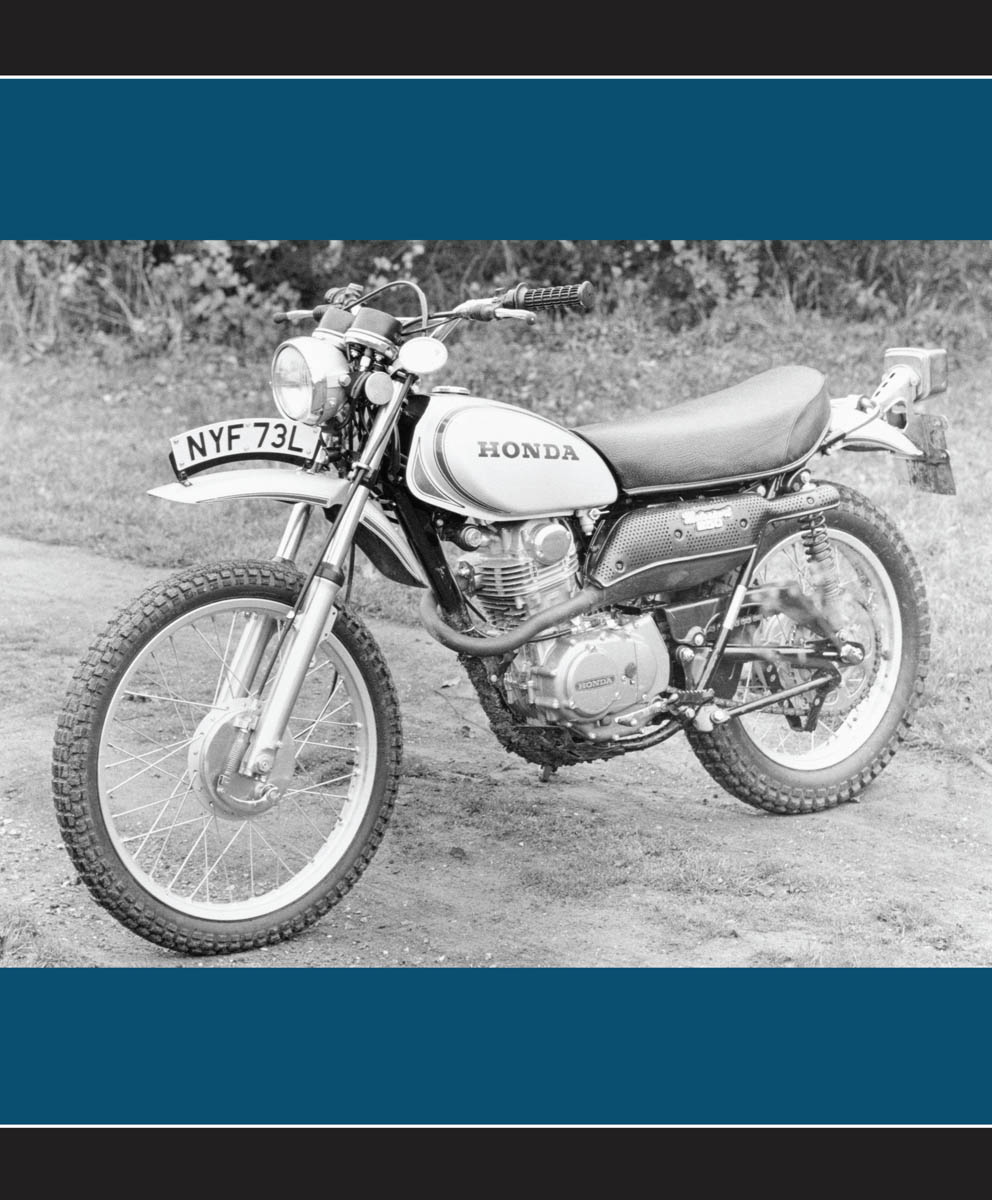

In order to understand fully how the G/S came about, why it was such a surprise and how significantly it broke with prevailing motorcycling convention, it is important to understand both the motorcycling world in general in the mid-to-late 1970s and BMWs place within it. Until the arrival of the G/S, the very idea of the trail bike that is, a road-legal machine that was capable both on and off road was still very much in its infancy. Pure competition-bred dirt bikes such as motocross and trials machines, or even more specialist speedway, grass and flat trackers, had been around for decades, but the first real dual-purpose four-stroke machine, Hondas XL250, arrived only in 1972.

Hondas XL250 of 1972 was the first large-capacity four-stroke put on to the mass market. It was a huge success.

The impact of the Honda had been instant, finding popularity, particularly in the US market, as a leisure machine. It was enough to spark a whole breed of Japanese rivals, all following a similar template of small-capacity, single-cylinder engines, long-travel suspension, rugged scrambler styling and basic road equipment.

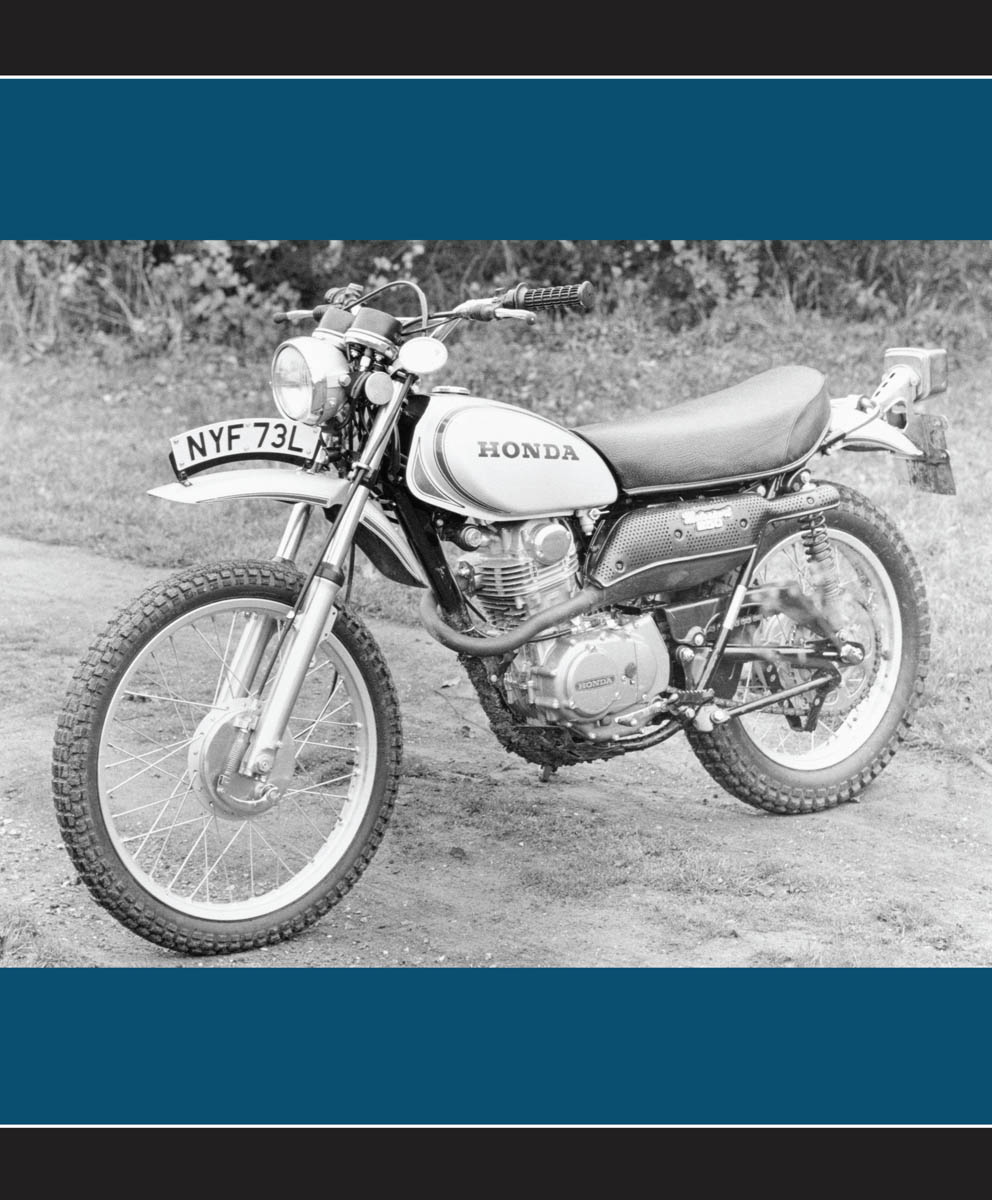

The next big development came in 1975 with the arrival of Yamahas XT500, the first of the so-called big four-stroke trailies and a machine which, at the time, seemed to set the limit for engine size in the class. After all, the XT seemed to have more than sufficient performance if the engine had been any bigger, it would also have increased the bikes weight and vibration, which would have been unacceptable in an off-roader or a roadster. Increasing the number of cylinders, meanwhile, seemed simply absurd.

So where was BMW in relation to all this? Quite simply, it was nowhere. Until the late 1970s the historic Bavarian marque had a fairly staid image, associated mostly with touring machines. A lightweight enduro seemed about as likely to come out of Munich as a rip-snorting sportster.

At the same time, BMW was also facing increasing commercial difficulties as it began to struggle in the face of the ever-increasing variety and technical sophistication of the Japanese Big Four. As the 1970s wore on, Honda, Yamaha, Suzuki and Kawasaki grew to dominate not just the lightweight classes, as they had done since the 60s, but also, increasingly, BMWs home ground of large-capacity motorcycling. The Japanese were offering four-cylinder superbikes such as the CB750, GS1000 and Z900, alongside something for every taste and pocket in every conceivable niche. BMW, with its premium prices, dowdy image and old-fashioned, air-cooled, shaft-drive boxer twins, was suddenly in big trouble. In short, it needed something attention-grabbing, affordable and new and it needed it quick.

Yamaha raised the bar for the big-bore trail bike still further in 1975 with its XT500, which was even larger than the Honda.

THE ENDURO SCENE

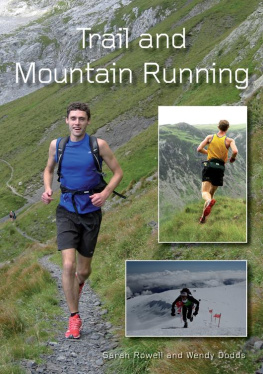

Thankfully for BMW, its high prices and old-fashioned image did not tell the whole story. Although the German marque had never commercially produced an enduro or trail bike, nor was it renowned for any kind of dirt pedigree, it certainly was not new to off-roading in fact, it had been involved in the sport for over fifty years. In the 1920s and 30s it had been particularly successful in six-day events, the endurance form of enduro, and in the 1950s and 60s it had won more than its fair share of silverware. This success continued into the early 70s, when the firm produced a series of works machines to compete in both the 500cc+ class of the German off-road championship and the prestigious International Six Days Trial.

During this period one rider rose to prominence on the German scene above all others. Herbert Schek was not just a giant physically, at around seven feet tall, he also towered above everyone else on the domestic off-road sport scene. He won the German championship in 1970 and 1971 aboard a BMW factory machine based on an R75 tourer, then in 1972, after the factory pulled out, completely undaunted he built his own BMW-based bike and promptly won again.

It could not last, of course. A fearsome new 500cc two-stroke from compatriot manufacturer Maico soon gained the upper hand and dominated the category for the next few years. However, even during the era of Maicos dominance, BMW did not stay idle: In 1975 BMW factory suspension engineer Rudiger Gutsche also built himself an enduro based on an R75/5 and was a regular on the German enduro scene both as competitor and marshal. There were many others, too.

This passion for enduro within BMW grew in parallel with the growing commercial popularity of road-going trail bikes such as the XL250 and XT500. The problem was that BMW did not have anything to sell. If only it could come up with something to compete with the Japanese, its commercial problems might be solved. The will was certainly there; they just had to find the way.

Another factor then came into play. While BMW had been outclassed by the two-stroke Maicos in the up to 750cc class of the German series, this was about to change: a reorganization of the categories occurred and a new class for 750cc+ machines was introduced. It was a class that was tailor-made for BMW. While this development did not in itself spark the creation of the road-going G/S, it was a significant step in the right direction: The factory decided to once again develop an off-road competition boxer twin.

Although BMW did not produce enduro machines, modified versions of its road machines were popular in off-road sport. Kurt Disler rode his version in the 1968 International Six Days Trial (ISDT).

Next page