Ring of Fire: an Indonesian Odyssey

dedication

This book is fondly dedicated to those special people who are least likely to see it, the tribal peoples of the islands, who took us in hand, treated us as equals, and opened their lives to us.

Acknowledgements

Of the numerous people who have, over the years, helped make Ring of Fire possible, and who are not already mentioned in the book or credited in the films, we would particularly like to thank the following:

Monie Adams; The Keraing, Andi Banawa and his wife, Ibu Desa; Julian and Julis Boileau; Jan Butchofsky; Soedarmadji Damais; The Tans Hans family; Raden Temenggung Jarjonagoro; Virginia Holshuh; Indonesian Directorate-General of Tourism; Michael and Robert Kennedy; Perry Kessler; Claire Leimbach; Donaldine Lourensz; James and Aune Nelson; Sydney Perret; Dorothy Pittman; Putrayala; Robert Seiffert; James Seligman; Gusti Made Simung; Alyson Steffen; Hal Stone; Harifin Sugeanto; Charles Twing; Jack Weru.

All photos Lorne and Lawrence Blair, unless otherwise stated. All photos reproduced by kind permission of the copyright owners.

Foreword

When I was preparing for my first visit to Indonesia, in the early 1990s, I was holed up in a seedy hotel in one of Bangkoks more disreputable neighbourhoods. The hotel offered few services and no charm, but seedy as it was, it did have a shelf of books that guests could borrow. One of them was a well-thumbed, nearly disbound copy of Ring of Fire, recounting a grand tour of the archipelago by ship by the brothers Blair. I snagged the book and brought it up to my room to read. My first trip to Indonesia was also to be a grand tour, beginning in North Sumatra, with a trip to Nias, and ending in the Bandas. I consulted the books index and was disappointed to see that the authors hadnt called at Nias, but Banda was there. So I turned to page 130 and read: On the dawn of the second day we discerned the smoke-wreathed cone of the Banda volcano perched on the horizon like a veiled Egyptian pyramid.

I was hooked on the book, I mean. I had been hooked on Indonesia years before I came here; Joseph Conrad had taken care of that. No footloose wanderer in Southeast Asia worth his flip-flops can long resist the siren allure of the great tropical archipelago. I had previously read about Banda, its strategic importance in history, how the Dutch had swapped Manhattan for the tiny islands nutmeg groves. But the Blairs faintly lavender-tinged prose appealed directly to the dreamy boy who grew up in Texas reading Lord Jim and Treasure Island, and the whole romantic boys literature of sailing ships and deserted tropical isles. I immediately turned back to the beginning and read the book from start to finish.

So while it would not be accurate to say that Ring of Fire inspired me to undertake my first voyage to Indonesia, it did remind me why. A veiled Egyptian volcano: Yes! A few weeks later when I cruised into the narrow strait between the fairytale port town of Bandanaira and the smoking volcano, the experience was just as magical as the Blairs had described it. That lavender tinge in the prose was simply reporting: if anything, it was austere compared with the spine-tingling reality of discovering an isolated group of islands like the Bandas. To capture that sense of remoteness, of mystery, is an essential aspect of writing about the archipelago, and no one in modern times has done it better.

I have recommended Ring of Fire over the years, blissfully unaware that it had fallen out of print: how could that be? Its one of the essential modern texts about Indonesias far-flung islands. Now it is back, and all lovers of Indonesia, its people and its critters, rejoice. As Lawrence Blair notes in his introduction for this new edition, there have been many changes in the archipelago since the voyage described in this book, and few for the better, but the air of enchantment, the brute charm of these islands is indestructible.

Jamie James

Kerobokan, Bali 2009

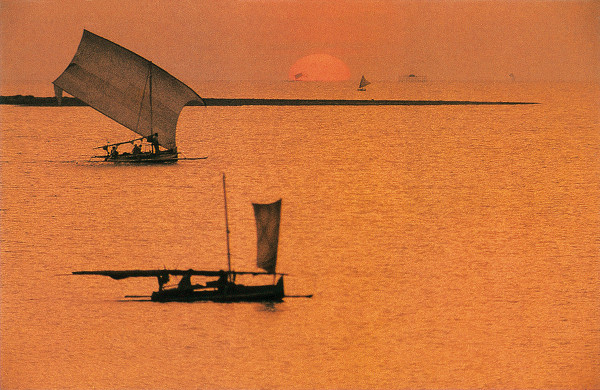

Outriggers slipping out to fish. (Lorne & Lawrence Blair)

Introduction

This book was hurriedly written during an icy winter in Boston, Massachusetts, while also writing the dialogue for our Ring of Fire film series, which my brother Lorne was simultaneously editing. Our bluff had been called, and after 10 years of independently filming nine separate expeditions in Indonesia, followed by 15 years of being unable to sell them, Public Broadcasting in the United States, in conjunction with the BBC, had finally picked up our work and required that we condense our adventures into four one-hour episodes by yesterday.

The book was intended to match the film series and describe what isnt seen on camera, which of course is virtually everything. The films and the book are thus corollaries, and have oddly circled and sustained each other, like twin-orbiting stars, in various packaging incarnations, down to the present day.

Re-reading the book for the first time since correcting the proofs in l988, I find my nose is rubbed in the enormity of change over these merely 20 some years. There is the death of my brother Lorne, in 1995, the reduction of Indonesias forests by nearly a third the equivalent to the entire land surface of Japan or California the doubling of the nations population from 120 million to more than 240 million souls, and the birth thrashings of a newborn democracy, with its accompanying rising tide of plastic. If I was just sitting in Bali, watching the rising tide, I might even feel depressed, but as I still produce adventure films and spend several months a year exploring the out-islands on private charter cruises, its heartening to know that vast tracts of the nation still remain wonderfully wild and mysterious, and mirror the unexplored recesses hidden within all of us, everywhere.

Just a few of the discoveries from Indonesia over these last two decades include the worlds largest cockroach, the worlds smallest fish, a blood-sucking vampire moth, and the first known poisonous bird, the Hooded Pitohui (Pitohui dichrous), with toxic oil in its black and orange feathers. Also discovered is an Asian population of the Coelacanth, the four-limbed, 350-million-year-old pre-fish, over six feet long, which hasnt changed since long before the time of the first creature to crawl on land and struggle for breath.

And theres the Mimic Octopus (Thaumoctopus mimicus), who was hard to find because hes seldom himself. He transmogrifies, at the drop of a hat, into as many as 16 (so far counted) other marine species including sea snakes, lionfish, stingrays and jelly-fish. He mimics with sufficient accuracy to have utterly fooled marine biologists who for 50 years have had the benefit of scuba gear to look him in the face. To me, all these creatures reveal more about ourselves, our protean diversity and our evolving capacity to see whats actually going on with this thing called Life on earth.

Also from Indonesia, in only 2003, was the startling discovery of the remains of the hobbit, Homo floresiensis, not sapiens, like us, but a different species of human, who was three feet tall and lived until as recently as only 10,000 years ago. We had thought that our species of Homo, sapiens, had been alone for the past some 35,000 years, ever since the demise of Neanderthal man in Europe then up pops this little elf, our first cousin, alive at the same time as ourselves, sapiens, hunting pygmy elephants and giant rats. The tiny people and cow-sized elephants are gone, but the Giant Rat of Flores lives on! And somehow, so do you and I.