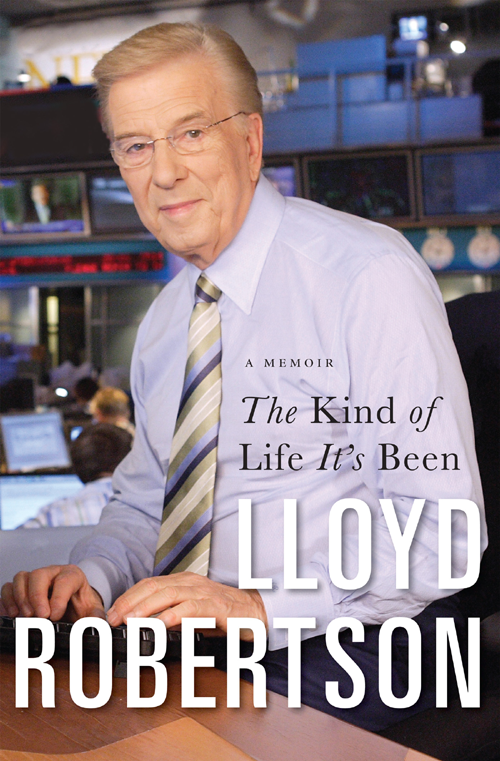

1

The Awakening

I T WAS A CLASSIC CANADIAN WINTER DAY IN SOUTHERN Ontario: bright sunshine, cold and crisp, with the hard-packed snow crackling underfoot on the edge of the sidewalks. January 16, 1946: my hometown of Stratford, Ontario, was decked out for a major event. The Union Flag of the British Empire, better known as the Union Jack, adorned storefronts, hung from balconies and was clasped tightly in the hands of the majority who turned out. There was merriment in the air; for the more thoughtful, there was also a sense of history. This, after all, was the day our little community was welcoming the boys homethe dads, brothers, relatives and neighbours who had fought in the Perth Regiment during the Second World War. This was their parade; they were survivors of that cataclysmic chapter of the twentieth century, and our town had been a part of it, sharing in both the pain and the glory.

As an eager and excited youngster on the cusp of my twelfth birthday, I scrambled for a good viewing position. My father was too old to have fought in the war, but I was aware of many other dads who had, and some who had made the supreme sacrifice. So for everyone in Stratford, this was the place to be on this day. My friends and I found a perfect location, hanging on to the supports of a platform put in place for the broadcasters at CJCS, the local radio station. When the bands and soldiers swung into view and the commentators began to describe the scene, I was swept up in the excitement of the moment and that buoyant feeling that stayed with me on big broadcast occasions for all of my life: I was there at the centre of something important, something bigger than myself and of interest to the wider community. Its hard to say whether some tiny seed was planted in my consciousness that daythere was no blinding revelation, no dropping of the penny. I just remember being fascinated by the voices of the two commentators as they painted vivid pictures of the marchers and the joyous crowds. Ken Dougan, one of the two announcers, possessed a powerful, deep baritone voice. He was floored when, many years later while working with him at the CBC in Ottawa, I was able to relate the story of that winter day in Stratford.

I look back on that January afternoon as the beginning of my awakening to a new realization: radio could transport me into a different world. I became fascinated with all of the voices on the local radio station and could identify every one of them when they started to speak. They became my heroes. Other kids may have been wowed by Superman, hockeys Howie Meeker or movie star Humphrey Bogart, but for me, it was the collection of personalities that spoke to me through my hometown radio station.

I was soon among the enthusiastic groupies of CJCS, located above the beer parlour in the Windsor Hotel. Somehow I talked my way into becoming a regular visitor. It bothered some of the announcers that this bratty kid wanted to sit in the studio with them and watch while they went through their daily routines of news, sports and weather and, with the requisite amount of mock enthusiasm, rolled the records of the big bands of the dayAll right everybody, lets swing and sway with Sammy Kaye. It cramped their style when they wanted to slip downstairs for a beer, rant about the boss or invite a girlfriend up for a Sunday afternoon liaison. Eventually, the station manager told me he had to ask me to leave and would I please stay away for a while. I had no choice but to comply.

He couldnt have known, as I certainly didnt, that Id be back working there in a few years. I simply transferred my thirst for radio elsewhere. Fortunately, for as long as I can remember, Id been blessed with a good voice that attracted attention wherever I went, and that perhaps gave me the confidence to be a little more forward than I should have been at times. At Shakespeare Public School (all Stratford schools were named after Shakespeare and his characters) I approached the principal, E.R. Crawford, an authoritarian figure with a soft heart, and told him I would like to help with the morning announcements over the internal public address system. He agreed, and I soon found myself alternating on those daily shows with a cheery, apple-cheeked girl by the name of Annetta Young. Until my arrival, Annetta had these slots all to herself, but if she was jealous, she never showed it; in fact, she was helpful. It could be seen as my first lesson in professional decorum.

At home, I was an avid fan of the great variety shows of the postwar years hosted by Fred Allen and Jack Benny and Canadians Wayne and Shuster. There were also the Saturday night hockey broadcasts of Foster Hewitt and the news with Lorne Greene, long before he left for Hollywood and a rapid ascent to stardom in the early TV series Bonanza.

The radio also provided an escape from a dreary home life. My father, George, was sixty years old when I was born. By the time I was five, he was retired on a tiny pension from his job as a machinists helper at the Canadian National Railways locomotive repair shops in Stratford. During my early years, he became ill with a series of stomach disorders, which caused him much pain and were accompanied by loud retching and vomiting during the night. Those were the sounds that echoed through the house in the small hours, causing much nervousness and concern to a young boy. As I peered out fearfully through my slightly opened bedroom door, I watched my poor mother, Lilly, run back and forth in the dimly lit upstairs hallway, wringing her hands, not knowing how to cope. She was tortured by immense problems of her own from a string of mental and emotional disorders: anxiety neuroses, deep paranoia and extreme obsessive-compulsive behaviour. She would stand for hours in the kitchen, drying a single dish while rocking back and forth, lost in her own reveries. Her muffled cries could be heard in the night, and for days on end she wouldnt emerge from her bedroom. It all meant she was hospitalized much of the time while I was young, and when at home her erratic behaviour and dark moods cast a gloomy pall over the household. She constantly warned against playing with certain boys because their parents were out to harm us, or, from her insecurities of being born a gardeners daughter on estates in England, she chided me: You should know your place and Youre getting too big for your britches. The visits to the psychiatric hospital in St. Thomas, Ontario, are forever etched in my mind: the images of the poor souls who stood frozen in catatonic states in the hallways or walked along babbling to themselves in strings of loud incoherence, the occasional anguished cries and screams from patients behind locked doors who were dealing with their own demons in the deepest recesses of their imaginings. All of this left me with a lifelong commitment to try to help in every way possible to uncover the mysteries of mental illness.

During my mothers occasional periods at home, her anxieties kept us suspended in turmoil. Her constant suspicions that neighbours were spying on us frayed any friendly relationships we might have had. Since she was totally stymied by how to handle a small child, before I was old enough to go to school she would leave me in my room all morning, until my father recognized what was happening and arranged to have someone look in on me. Eventually, the frustrated psychiatrists, with no medication available to help them, recommended a prefrontal lobotomy, a popular operation of the day, long since discredited, that was used to calm frenetic psychotics or others who were deemed untreatable. In the 1975 movie