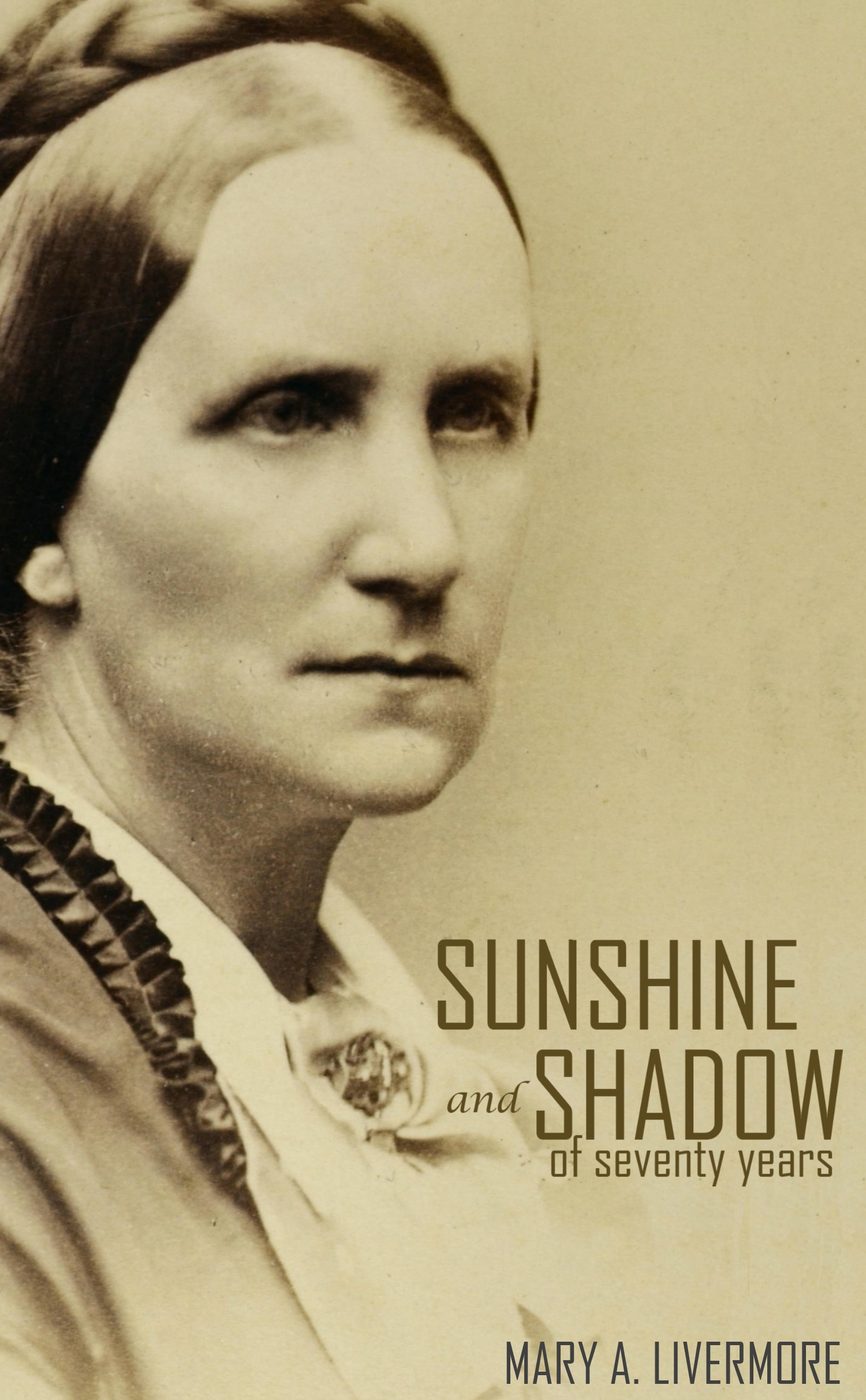

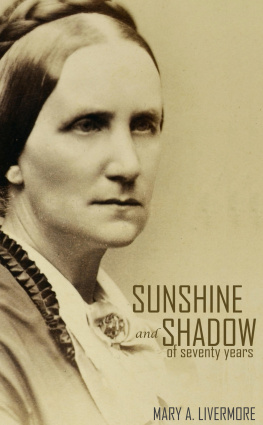

SUNSHINE AND SHADOW OF SEVENTY YEARS

MARY A. LIVERMORE

TEACHER, AUTHOR, WIFE, MOTHER, ARMY NURSE, SOLDIERS FRIEND, LECTURER, AND REFORMER

1897

2014 Get more great reading from BIG BYTE BOOKS

PREFACE

FOR many years I have had a vague, half-formed purpose to write my biography for my children and grandchildren. They have urged it again and again, and have volunteered their assistance

Their importunities have been life-long friends, who have grown have offered to assist me with reminiscences of my youth, memoranda of events that occurred during our school life, and with packages of my own letters, running through half a century, the oldest Of them dating back more than sixty years.

My father and mother during my girlhood religiously preserved my weekly letters to them, which were always packed with my experiences at the time, as these were what they cared most to know. And my faithful husband, during our long life together, has almost prepared a biography of one in his methodical collection, arrangement, and preservation of my letters and manuscripts, our experiences in the ministry, and our editorial co-partnership; in his memories of journeys, visits to historic places, and eminent people; in his reports of lectures, preservation of newspaper clippings relating to myself, of all sorts and from all parts of the country, and with copious memoranda of the prominent events of my life in general. There was no lack of material.

But it requires some courage to write ones biography. Every human soul has its secret chamber, which no one is allowed to invade. Our uncomforted sorrows, our tenderest and most exquisite loves, our remediless disappointments, our highest aspirations, our constantly baffled efforts for higher attainments, are known only to ourselves and God. We never talk of them. When these are counted out, with numerous events in which one has participated with living people, whose narration might leave a sting, the story of ones life seems to ones self to lose color, and to dwindle in its proportions. Who would care to read it? What good purpose would its publication subserve? If one outstays the average longevity of the race, the waters of oblivion close over him, and he is forgotten before he dies, while the ranks close up immediately when one drops on the march, and his very name is soon unheard. Why then write an autobiography at all? And I found my courage oozing out at the finger-tips, whenever I addressed myself to the task of telling the story of my life.

Not only lack of courage, but lack of time, delayed the fulfilment of my purpose, and held my biography in a nebulous state. The daily business of life is imperative, and calls for immediate attention. I am always sorely pressed by demands upon my time that cannot be held in abeyance, and should probably have postponed the preparation of this book until it was too late, but for the advent of my friend and publisher.

He represented to me that I had been identified with so many matters of wide interest daring my life that my decease would inevitably be the signal for the appearance of unauthorized, unreliable, and shabby biographies. And he urged that it would be much the wiser way for me to take time by the forelock, and write my story myself. It would be more satisfactory to my family and friends, and would secure a larger number of readers. Before his visit was ended, the whole matter was put on a business basis, and I had contracted to place my manuscript in his hands at a specified date.

As if to confirm his predictions, a lady called upon me, a few days later, as I was convalescing from a sharp attack of illness, bringing with her a prodigious bundle of manuscript, which she begged me to examine. I declined, for it was a formidable task, and I was ill. Then she besought me to, give her information, which I alone could furnish. And little by little it came out that she knew I had passed the dead line of three score years and ten, declared by the Psalmist to be the duration of human life, and hearing that I had been very ill, she had decided to take time by the forelock, as my publisher had advised me to do. She had been working on a sketch of my life, but lacked information concerning my early history, and if I would fill out the gaps in her narrative, she should be able to place her work in the hands of a publisher, whenever anything happened to me.

I was a little startled, and much amused. It seemed as if sentence of death was to be executed upon me immediately, so coolly and clearly did my unknown visitant inform me of my approaching demise. And the perfect nonchalance of her manner, when she requested me to help her complete a biography of myself that she might be able to put her book upon the market as soon as I had shuffled off this mortal coil, was most amusing. I informed her that a story of my life would probably be published in advance of hers, and perhaps while I yet lived, and that her manuscript must be suppressed. For now I examined it in part, and found it very inaccurate and unreliable. But it required a long and very plain discussion of the whole matter before I succeeded in convincing her that my publisher, my family, and myself had rights which she would infringe if she persisted in publishing her incorrect, badly written, and unauthorized manuscript.

If I should pass out of life before this book is published, I wish it distinctly understood that this is the only biography of myself that I have authorized, and the only one that is reliable. No other that may appear has received any sanction from me, or from any member of my family.

I have given more space to the story of my three years life in Virginia than I had intended. But after re-reading, I have decided not to abridge the narrative. It is a story of plantation life at the South, fifty-five years ago, and presents a phase of society and civilization that has passed away forever, and, as such, may prove of value and interest to young readers. It was written from a journal carefully kept at the time, from my copious weekly letters home to my parents, and from my correspondence with the family on my return North.

In those days letters were letters, written with care, packed with details, highly prized, and carefully preserved. Every one of my letters home contained two sheets of foolscap, closely written on both sides, and each one cost my father twenty-five or thirty-seven and a half cents postage. At that time the receiver of a letter paid the postage, and not the sender, as now. The postage was increased with the increase of sheets of paper in the letter, letters not being paid for by weight, as at present. And on occasions, when some unusual event had tempted me to send home some half dozen or more sheets of gossip, my father has paid fifty cents postage on the letter, and there were times when that sum was exceeded.

I cannot but hope that the story of my life may prove interesting to my friends and acquaintances, and to others into whose hands it may fall. It has been interesting to me while I have been living it, although entirely different from what I had planned and hoped. Eventful, and full of variety, I have never found it dull, and have never suffered from ennui. I have had little cause for complaint, although my life has been a long struggle. There has always been some good thing to strive for and to win, or some evil to be suppressed and rooted out. And I have felt so kindly an interest in the men and women among whom my lot has been cast that I have carried on my shoulders and in my heart many of their burdens and sorrows, and been gladdened by their happiness. Generally I have won that which I have sought, and have most highly valued.

Next page

![Mary Ashton Livermore - My Story Of The War: A Womans Narrative Of Four Years Personal Experience As Nurse In The Union Army [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/420175/thumbs/mary-ashton-livermore-my-story-of-the-war-a.jpg)