Table of Contents

FOREWORD

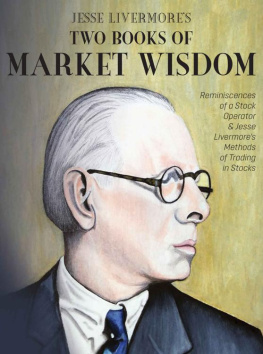

I first read Reminiscences in 1976. It was given to me by my first boss as the most important book I could read. It resonated with me on a variety of levels. First, Livermore started with but a few coins in his pocket, and as a relatively penniless 21-year-old when I first read it, it was both reassuring and hopeful. His stories of making millions, hobnobbing with other great financiers and stock market operators, trading from a yacht, and deftly maneuvering through the great commodity and stock corners of the day was the financial equivalent of sex, drugs and rock n roll to a young man at the advent of his financial career. Secondly, his facility with numbers was very similar to mine. It was as if he spoke straight to my soul in this regard. Finally, probably the greatest message I took away from my first read had to do with understanding price action. There are times when every market has a story to tell. And you have to train yourself to be both a great observer and listener, or you will be too late to enjoy the full story that will be told.

I have read the book countless times in my career, and I cannot remember a single time when I havent discovered something new. As I was reading it again for umpteenth time, I noticed on page three it reads that Livingston used to journal both the determination of (probable price) movements as well as assorted record of my hits and misses. I have been doing this semi-religiously for most of the past three decades, and I always thought it was my own invention. Over the years, I guess I deluded myself into taking credit for a brilliant practice integral to my success by conveniently forgetting the inventor. And this points to why this book is so important to me and why anyone looking to take up trading as a profession should read and study it. It is a textbook for speculation. Indeed, I hand a copy to every new trader we have, regardless of his or her considerable experience. I am always looking for the next Jesse Livermore.

Paul Tudor Jones

Chairman and Chief Executive

Tudor Investment Corporation

For more Paul Tudor Jones thoughts on the book, please see page 399.

PREFACE

Imagine it is 1923. The horrors of World War I, in which 37 million men and women were killed or wounded, are still fresh in your mind. So are the horrors of the great flu pandemic of 1918-1919, which killed more than 50 million people worldwide. So are the great economic and psychological setbacks of two terrible postwar recessions in 1919 and 1921.

The cumulative gloom produced by the ravages of man and nature is hard to shake. Business in most industries is perking up a bit finally, but the stock market is reflecting a sour mood. Despite some dramatic ups and downs, prices are still pretty much where they were eight years ago.

Yet in this fallow ground of despair and fear, seeds of hope are being plantedand the dreams of ambitious, hardworking Americans are beginning to stir.

Families are starting to pour into cities from the countryside in the largest urban migration that the country has ever witnessed, and they all need new homes, water systems, transportation, offices, factories, and entertainment. Banks are beginning to feel more confident, and are doling out loans to industrialists with good ideas for cars, railroads, consumer goods, and resorts. Mass-market advertising is emerging for the first time to hawk goods over the radio, which has just begun to broadcast jazz music and baseball games after low-cost vacuum tubes have made home receivers affordable. The first talking motion pictures are emerging, a dazzling innovation that has begun to transmit American values worldwide for the first time.

Amid this growing sense of comfort and confidence, the stock market has finally begun to arch higher, and popular weekly publications are soon filled with stories of average people leveraging their wages to make a killing in stocks. Newspapers are covering Wall Street with lan, offering detailed reports on commodities and equities and the people and forces behind their mysterious movements.

Little did anyone know at the time, though in hindsight hints were abundant, that the market was about to surge 400 percent in the greatest single six-year span in its history. And so the time was ripe for the emergence of heroes to enthrall investors imaginations and spark latent animal spirits.

Witnessing this swelling sentiment for speculation was a veteran magazine writer and novelist named Edwin Lefevre. Born in Panama to American parents, and already well traveled in Asia and South America by his twenties, Lefevre was attracted to the New York financial markets as an observer, and after finding regular work as a journalist he parlayed his keen analytical skills and buoyant personality to become one of the eras savviest chroniclerswriting and editing dozens of articles on Wall Street personalities and strategies. He stood apart from the boosterism of colleagues by primarily focusing on the gray underside of the change in stock prices, preferring to uncover tales of scammers, swindlers, and tricksters who preyed on the publics gullibility to fatten their own ledgers. He was no moralizing prude, however, and counted giants of speculation like James Keene among his friends.

By the early 1920s, at about 50 years old, Lefevre recognized that even the smartest journalism failed to get at the very essence of the truths he had uncovered about Wall Street, so he decided to shift gears and try his hand at transcending the bounds of quotes and facts by writing a new type of fiction. Casting about for a central character on which to hang his story, he had a great number of candidates to choose from, as he was well regarded by many of the eras top players. Most were relentless self-promoters well known to the public, so it was a little odd that he ultimately chose the notoriously reticent Jesse Lauriston Livermore as his foil. Perhaps it was the challenge.

Livermore had been raised on a rocky farm in Massachusetts and had risen through hard work, ambition, necessity, persistence, guts, and a sharp mind for numbers to become one of the greatest traders of stocks and commodities of the first two decades of the twentieth century. He had made and lost more fortunes by the age of 25 than most people will see in a lifetime, and though he rarely spoke to the press about his exploits and eschewed the companionship of partnerspreferring to play what he called a lone handhe possessed an unusual level of self-knowledge and could express his tradecraft and mental state in colorful, perceptive ways that eluded most professionals.

The two met for an initial series of interviews to size each other up. Lefevre was impressed by Livermores cool intelligence, while Livermore appreciated Lefevres willingness to tell uncomfortable truths. Both were frustrated at how the public blamed their misfortunes on the market and the big operators of the day when, in fact, they had only their ignorance and overconfidence to blame.

The author apparently viewed the traders little-known rags-to-riches story as an ideal vessel into which he could mix his own views about all that was deceitful, wretched, and corrupt, yet also energizing and transcendent, about Wall Street. Although Livermore was reclusive and shy, he proved more than willing to share his lifes story with someone of such rich creative talent. The tale that emerged