Contents

Guide

Since 1888, the National Geographic Society has funded more than 14,000 research, conservation, education, and storytelling projects around the world. National Geographic Partners distributes a portion of the funds it receives from your purchase to National Geographic Society to support programs including the conservation of animals and their habitats.

Get closer to National Geographic Explorers and photographers, and connect with our global community. Join us today at nationalgeographic.org/joinus

For rights or permissions inquiries, please contact National Geographic Books Subsidiary Rights:

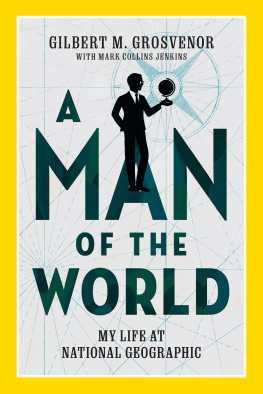

Copyright 2022 Gilbert M. Grosvenor. All rights reserved. Reproduction of the whole or any part of the contents without written permission from the publisher is prohibited.

NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC and Yellow Border Design are trademarks of the National Geographic Society, used under license.

Financially supported by the National Geographic Society.

ISBN: 978-1-4262-2153-8

eBook ISBN: 978-1-4262-2154-5

22/MP-PCML/1

To the Geographic family: the people who made this iconic institution what it is today

Y ou may not know my name. But chances are you have encountered my family legacyperhaps in rows of neatly aligned yellow magazines, on television, or online, where our social media channels are followed by an audience of nearly 200 million. You might know some of our milestone accomplishments, which include funding the initial fieldwork of a young scientist named Jane Goodall studying chimpanzees in Africa and bringing the discovery of the Titanic to the worlds attention.

I was born into this worldthe National Geographic familyas the fifth generation fortunate enough to spend a lifetime searching out and celebrating the planet, pledged, in the words of our mission, to increase and diffuse geographical knowledge.

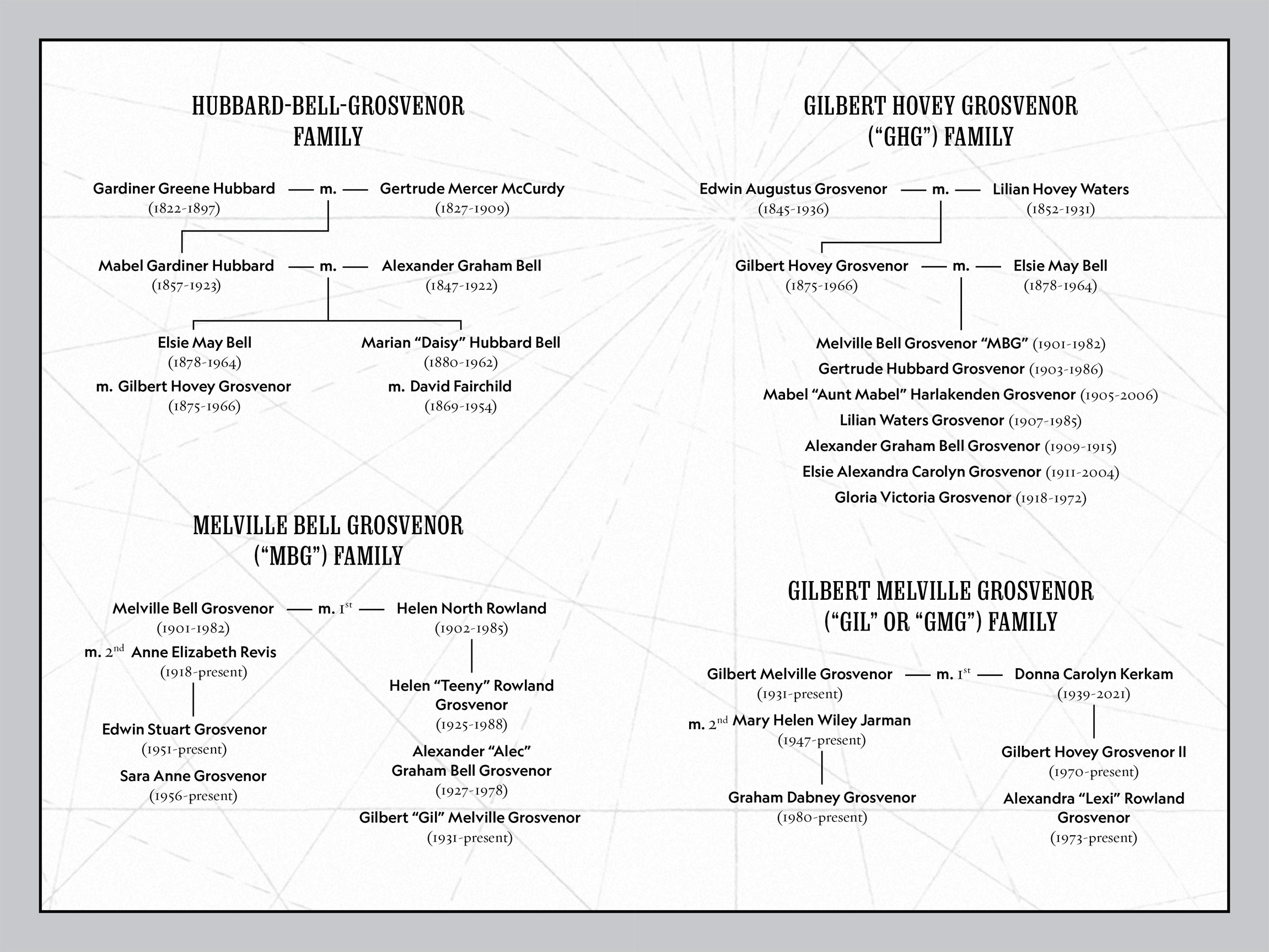

My great-grandfather Alexander Graham Bell, inventor of the telephone, was an original member, with 165 like-minded scientists and explorers, of the National Geographic Society. My grandfather Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor was the first full-time editor of National Geographic magazine, a cherished institution and global magazine of record. My father, Melville Bell Grosvenor, his successor, helped make scientists like Jacques Cousteau a household name.

But in the world of National Geographic, family meant something broader and deeper than my own forebearers. It encompassed writers, photographers, engravers, artistsin short, an entire staff at our fabled headquarters in Washington, D.C. Most of all, it meant our membersthose who supported our efforts and, in turn, received our flagship magazine, books, globes, atlases, and more. For much of our history, in order to share in the National Geographic experience, one had to be a member of the Society.

The map of my life was charted by men and women curious about the scope of our planet who wanted to pass along that sense of wonder to anyone who ever marveled at an endless horizon, a velvet sky at night, or the oceans deep azure. They inspired me to embrace this place we call home, and to inspire others to do the same.

We see a good deal of the world, the photographer Margaret Bourke-White once said. Our obligation is to pass it on to others. From its founding, the National Geographic Society met that obligation and continues to do so today.

This is the story of my family and the Society it helped create.

I n March 1979 I was in my office on the ninth floor of the National Geographic Societys headquarters in Washington, D.C., when I was told Al Giddings was on the line. Al was a longtime National Geographic contributor, and I was the magazines editor. I picked up the phone.

Hi, Al, I said.

Want to go diving at the North Pole?

I was about to make some crack about Santa Claus when I recalled that Al was filming a documentary in the Arctic.

Im serious. Joe MacInnis is on board, and the Canadians will let us use the LOREX floating ice station as our platform.

Joe, the worlds leading specialist in diving medicine, was also the worlds expert in under-ice diving. In 1973 he and four companions became the first humans to dive beneath the ice at the North Pole.

Hardly anyone has done it since, Al said. You can probably count them on your fingers. As editor of the Geographic, you should be the first journalist to do so!

I could feel the barb of the hook setting within me.

When do we leave? I asked.

Arctic exploration was a legacy of the institution to which I was devoting my life, as it was to every geographical society founded in the 19th century. Each in turn had urged a renewed quest for the elusive Arctic grail, the North Pole. In 1909 the National Geographic Society had helped sponsor the first expedition that attained that goal, a source of deep-seated institutional pride. My grandfather Gilbert Hovey Grosvenor, the pioneering editor of National Geographic magazine, had championed that expeditions leader, Robert E. Peary.

My grandfather, and my father after him, also sponsored Richard E. Byrd, the admiral of the ends of the Earth, who was the first to fly over the two antipodes. Others wed been associated with, like Roald Amundsen, Ernest Shackleton, and Wally Herbert, made clear the poles were in our blood.

In mid-April, I flew to Resolute Bay on barren Cornwallis Island, not far from the fabled Northwest Passage, where I met Joe. We took an old DC-3 across the Canadian Arctic Archipelagoall gray rock, brown tundra, and ice-choked seasto Alert, perched on the northern tip of Ellesmere Island. There we climbed aboard the de Havilland Twin Otter warming up for its supply run to the Lomonosov Ridge Experiment (LOREX) base camp.

The LOREX was Canadas effort to map its portion of an immense undersea mountain rangethe Lomonosov Ridgethat spanned the 1,100 miles between Ellesmere Island and Russia. National Geographic had lent the services of its deep-water photographic expert, Emory Kristof, to the camps scientists.

Aloft over the Arctic Ocean, I couldnt take my eyes off that endless expanse of whiteness beneath. Everything to the west had been marked Unexplored on a map my grandfather had published only a few years before I was born. Somewhere below was the track Peary had followed to the North Pole.

A floating island can be a challenge to find. But eventually the cluster of white tents and red Quonset huts loomed into view, and we set down on the improvised airstrip. For the next two days and nights we lived on a raft drifting at the stately pace of five miles a day.

Thats where the 26 scientists were spending two months profiling the undersea ridge with echolocation instruments. What little free time they had was spent in one of three places: a sleeping bag, the plywood sauna marked by a barber pole (the North Pole), or the LOREX Slum and Polar Bar tent, where an invigorating dram could be found.