Contents

An Ivy Book

Published by The Ballantine Publishing Group

Copyright 1998 by Larry Chambers

Introduction 2018 by Larry Chambers

All rights reserved under International and Pan-American Copyright Conventions. Published in the United States by The Ballantine Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Ivy and colophon are trademarks of Random House, Inc.

www.ballantinebooks.com

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 98-92823

ISBN9780804115759

Ebook ISBN9781101969564

v5.2_r1

a

Contents

Introduction

It is hard to write a new introduction to Death in the A Shau Valley after watching Ken Burnss eighteen-hour film The Vietnam War (released just two weeks ago as I write this). It is hard after everything I have learned about Vietnam and the lies and deceit that have surrounded it, and especially after all the hidden history I have found linking Ho Chi Minh and the United States OSS during World War Two. My journeys back to Vietnam and Cambodia in the past six years opened my eyes.

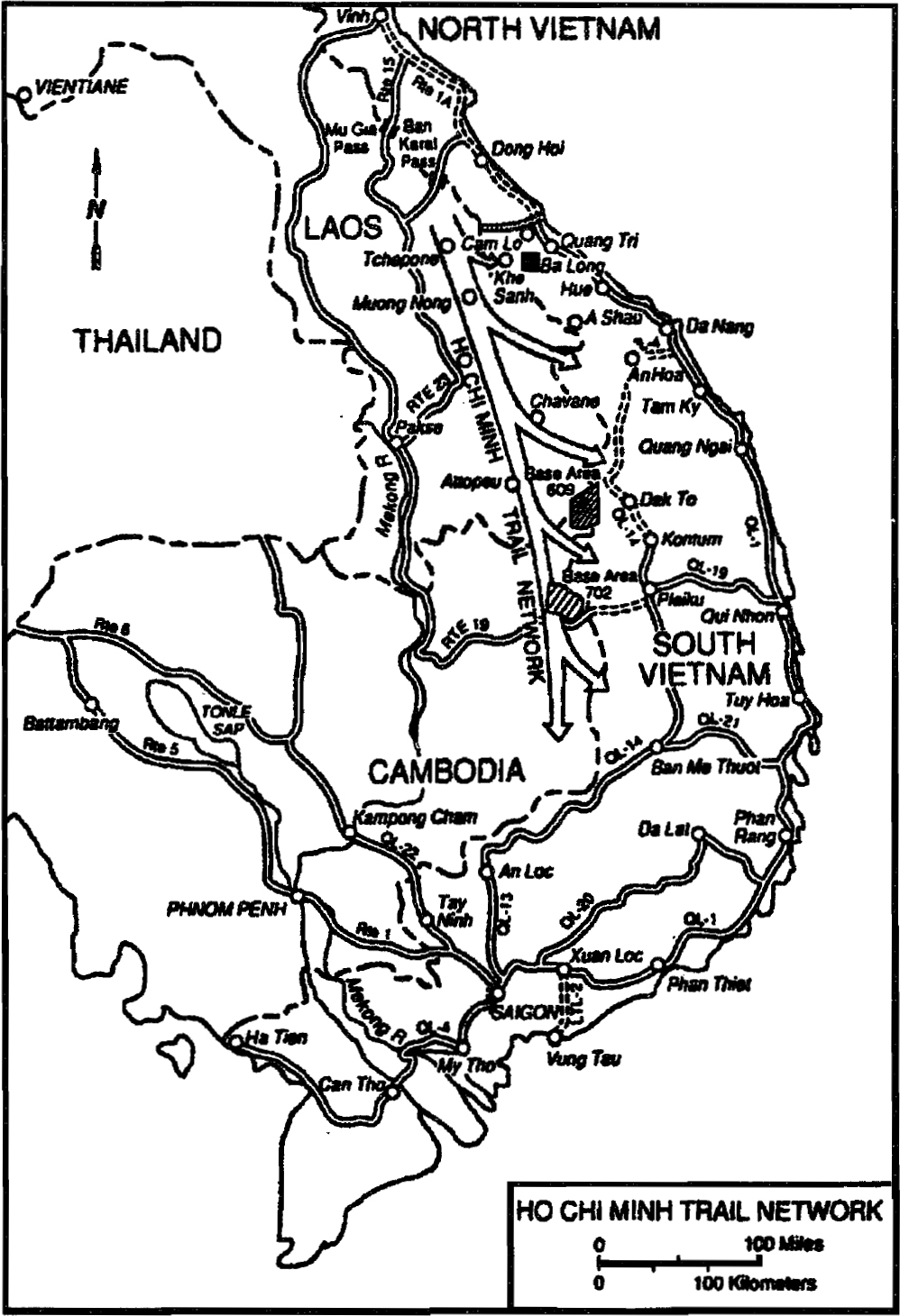

This book is about combat that took place in the A Shau Valley, where I pulled twenty or so long-range reconnaissance patrol (LRRP) missions, got hit by lightning, and first saw a WWII Japanese Zero fighter up close. The Zero sat like a rusting harbinger on the northern end of the Special Forces runway, which is today located in the Montagnard village town of A Luoi. When I first saw it, I wondered why it was there. Not until thirty years later, standing in the Ho Chi Minh archives in Hanoi, did I find out.

When I first went to Vietnam in 1968, I was young, idealistic, and naively patriotic. I didnt ask too many questions and I believed what my leaders said was true: the Viet Cong, like all communists, were evil beings whose only purpose in life was to destroy freedom in order to rule the worldand it would be up to us to stop them in Vietnam. I was a twenty-year-old undiagnosed dyslexic kid who had dropped out of college to join the Army, and the history of Vietnam was unknown to me.

As the years passed, I began to wake up and to recognize the cultural trance about Vietnam and the communist world that Americans were living in. What I have since learned is so bizarre and disturbing that the knowledge has elicited a powerful shift in my thinking about myself and the war that I participated ina war I felt obligated to defend for so many years.

There is no way that I can express the rage and anger I felt when I learned I had been lied to by my government. Presidents Lyndon Johnson and Richard Nixon were two of many who lied shamelessly whenever it was to their political advantage to do so.

After the war, I had no desire to return to Vietnam, forgive my enemy, or help the Vietnamese people, but that all changed once fate intervened. A chance meeting with someone who challenged my core beliefs resulted in my returning to Vietnam, with the intention of validating my position and proving the other party wrong. Much to my surprise, going back to Vietnam and seeing firsthand the Vietnamese people, learning the real history of Ho Chi Minh and the war that had been hidden from Americans, changed my worldview, allowing me to see the Vietnamese people in a different lightnot as gooks, dinks, or body count, but as people with happy families and beautiful children like my own.

Once my eyes were opened, I decided to return to research the multigenerational effects of U.S. military action upon the countries, populations, and cultures that we called our enemies. Ultimately, my research led me to the conclusion that practically everything Id once believed to be true wasnt.

Six years ago, after this epiphany, I began writing about my journey.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=y8Tu73bxazw

My first night back in Hanoi in 2012, I happened to watch an HBO documentary about Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara, who, just before his death, finally admitted he had been wrong about the U.S. invasion of Vietnam.

During my second trip to Hanoi, I saw an elderly woman begging on the street. Her hands were contorted and her face was so badly burned that my first instinct was to look away and hurry past. But I turned around and walked back, bent down, and gently placed a donation in her cup. I looked deeply into her eyes, and saw something I didnt haveinner peace. Then she cupped her hands in the prayer position, thanking me. Im sure she could tell I was an American, and she had every right to feel bitter and resentful, but she exuded only dignity, compassion, and forgiveness. That encounter reverberated to the very core of my being.

I had my second Aha! moment along a winding mountain road on the way to the A Shau Valley. As we drove, we found ourselves following behind a white Ford Courier truck with dark-tinted windows. My Vietnamese guide explained that its markings meant it was a body retrieval truck.

My first thought was that it was an American MIA recovery team looking for the last of the 1,641 U.S. servicemen still missing in Vietnam.

No, they are looking for missing dead North Vietnamese soldiers, the guide explained.

Until that day I had never entertained the thought that my former enemy, the North Vietnamese, could be concerned about finding their missing sons and daughtersas if humanity was somehow exclusive to Americans. In 1969, the common American soldiers belief had been that the Viet Cong were vermin-like beings incapable of human emotions. Traveling behind that body retrieval truck was a revelation to me of our shared humanity.

It has been over forty years, and theyre still looking for their missing. The problem is that their soldiers (the Peoples Army of Vietnam, which we referred to as the North Vietnamese Army, or NVA) wore no IDs such as the American soldiers dog tags, making identification of their deceased next to impossible. Even by conservative estimates, the war claimed the lives of more than three million Vietnamese, among them a million North Vietnamese soldiers. More than three hundred thousand are still missing.

The thought of the remains of an enemy soldier being inside that truck ripped me out of the present time and back to May 8, 1969, the day my best friend, Ron Reynolds, died.

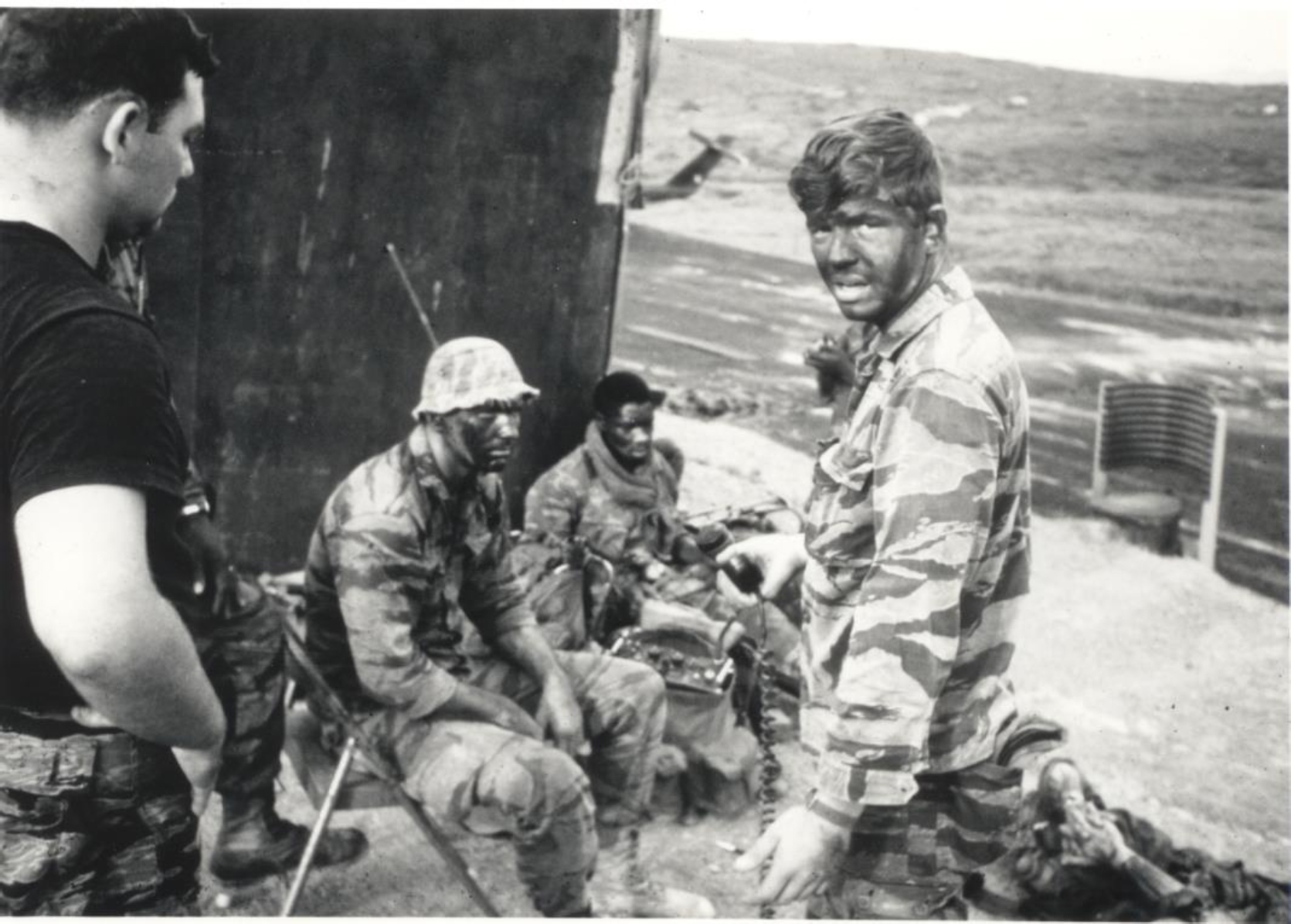

I can still remember Ron preparing to climb aboard his helicopter. He grabbed hold of my sleeve and looked at me solemnly.

I know Im not coming back, Ron told me. Caught off guard and not knowing what to say, I tried to lighten the mood.

Well, Ron, Id better take your last picture, then. I snapped a photograph of Ron, sitting with his arms hanging limp at his sides. Ray Zosack is holding the radio mic, Spec-4 Marvin Hillman sitting in the middle.

Later that afternoon, Ron walked into an ambush. Shot three times in the chest and mortally wounded, Ron lay in the open elephant grass alone until Doc Glasser crawled out to him and held him, waiting for the medevac helicopter to arrive. Glasser told me Rons last words were, Im thirsty.