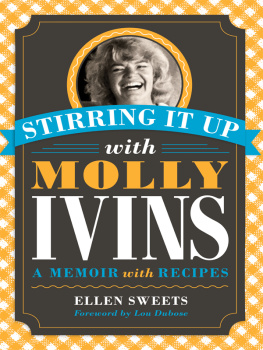

E very one of my five brothers was bred to play ball. For a long time it wasnt clear which of the boys would make it to the major leagues, but we had no doubt that The One was among us. We were the chosen. I do not recall a single moment of my childhood in which I was not imagining my familys lifeor my ownas an epic tale.

I kept a journal from the time I was seven years old. Across the thousands of pages, my handwriting changedthe wobbly print gave way first to a bloated cursive and then to a careful combination of print and scriptbut my purpose was unflagging. I was determined to redeem us, to save us not only from ourselves but also from the terrible possibility of being ordinary.

For their part, my family trusted me to write poignant and glowing accounts of its adventures and exploits. Knowing that our days would certainly be distilled into a heroic portrait of a certain America was a grave responsibility. My brothers, therefore, did not have time to worry about little things like social conventions or rules. They lived on an elevated plane, and their faith in future fame was absolute.

Before they were old enough to seriously practice the game, they spent hours in our backyard in Columbus, Ohio, tirelessly preparing themselves for the sound of the fans going wild. Ahhhhhhh! theyd gasp, bowing their heads, clenching their fists and stretching their arms straight up toward heaven. Aaaaaa haaaaaa haaaaaaaaa.

To create the sound of the fans going wild, they pushed hot air from their diaphragms up into the backs of their throats; then they added the sort of hacking that might signal the expulsion of a large blob of phlegm. Finally, they exhaled. The raspy, wheezing result approximated the distant roar of fans behind Red Barbers voice on the radio.

These public broadcasts contributed to our neighbors ongoing exasperation. My brothers, however, were not concerned. Day after day, they created a piece of performance art in which they were, simultaneously, the fans going wild, the player being honored, and the announcer describing the scene.

With no apparent provocation, the sound of fans would erupt from various points in the backyard.

Yeahhhhhhhhh, said the swing set.

Haaaaaa aaaaa aaaa, said the whirligig.

What could they be doing over there? said the neighbor.

Molly, cant you keep them quiet? yelled our mother.

Please, you guys, I pleaded.

But the fans could not be silenced by then, for the players had abandoned their positions and were stumbling toward the center of the yard. Their heads were down. Their mouths were open. Their eyes were squeezed shut. Their faces were wrinkled as if each were pushing a particularly challenging bowel movement. They collided, hugging and jumping on one another. They were falling together like ecstatic converts leveled by the spirit. They were a writhing pile of victory. And the fans were going wild.

Aaaaaaahhhhh!

Bark-cloth curtains rattled on their plastic rings throughout the neighborhood: Everything OK over there? Screen doors screeched openCan you keep it down?and slammed shut. Babies awoke howling from their naps and the anguished voices of other peoples mothers rose like thistles under our bare summer feet.

Does anybody even keep an eye on those kids?

But my brothers then rose from the pile of magnificent winners to become a team of commentators. They raced to the giant spruce in our front yard and scrambled up its branches. The tree was their radio tower. Each was determined to be the first to air the news. The spruce swayed precariously beneath the breathy wail of their broadcast. Boughs snapped. The trunk creaked. Dried needles showered down like ticker tape.

Did you see that! Im telling ya, that ONeill! What a shot!

He had some wood on that one, ONeill did! Heck, I dont think its landed yet!

What a hitter! ONeill won the ball game! He won the Series!

It happened every afternoon. It was so embarrassing. They were so pathetic.

My God, Molly, can you quiet them down? My mother was inside nursing the baby but with each wordAll Im asking for is a moments peace !she was gathering a head of steam and getting closer to the window.

For-heavens-sake-Molly-theyre-breaking-the-pine-tree-what-in-the-name-of-God-is-the-matter-with-you-get-them-out-of-there-oh-my-God-one-of-them-is-falling-get-him- Je -sus-Chrrrr- ist- is-there-no-end-to-this?

There was no end to it. And so, in the summer of 1962, I tried a different beginning. Im adopted, I told my friends. You know Anastasia, the youngest daughter of the czar, remember, that story in My Weekly Reader ? Thats my real mother. But dont tell anybody, I would add solemnly. Otherwise, people might think Im a communist.

My real brothers were princes who rode white steeds through snowy forests and defended my honor with gleaming lances, not these small serfs wielding fat red plastic bats on the patch of grass behind a modest suburban house in the Midwest. No wonder I didnt care about baseball: I was Russian!

I cultivated the habit of checking for my crownjust to make sure that I wasnt wearing it in public by mistake and drawing attention to myself. Pat, pat, pat, pat. Using index and middle fingers, I would touch four spots in a circle around the top of my head.

What in the name of God is the matter with you? said my (supposed) mother. Have you lost your mind?

I took great comfort in my secret and superior station in life, but my royal status also had unforeseen consequences: the more I became Anastasias daughter, the more keenly I suffered the pain of being deprived of a family who understood me. Then one evening Walter Cronkite mentioned Russia on the news. What the heck? said my (supposed) father as I rushed out the front door sobbing and trying to rend my garments.

As I came around the corner of the house, I saw that my mother had abandoned the dishes and was standing on the back stoop, waiting for my maniacal circuit to return me to our yard. I swerved to avoid her and headed for the maple tree. I flung my arms around its trunk and then, in what I hoped was heartbreaking desperation, began to wail.