Contents

Guide

Guide

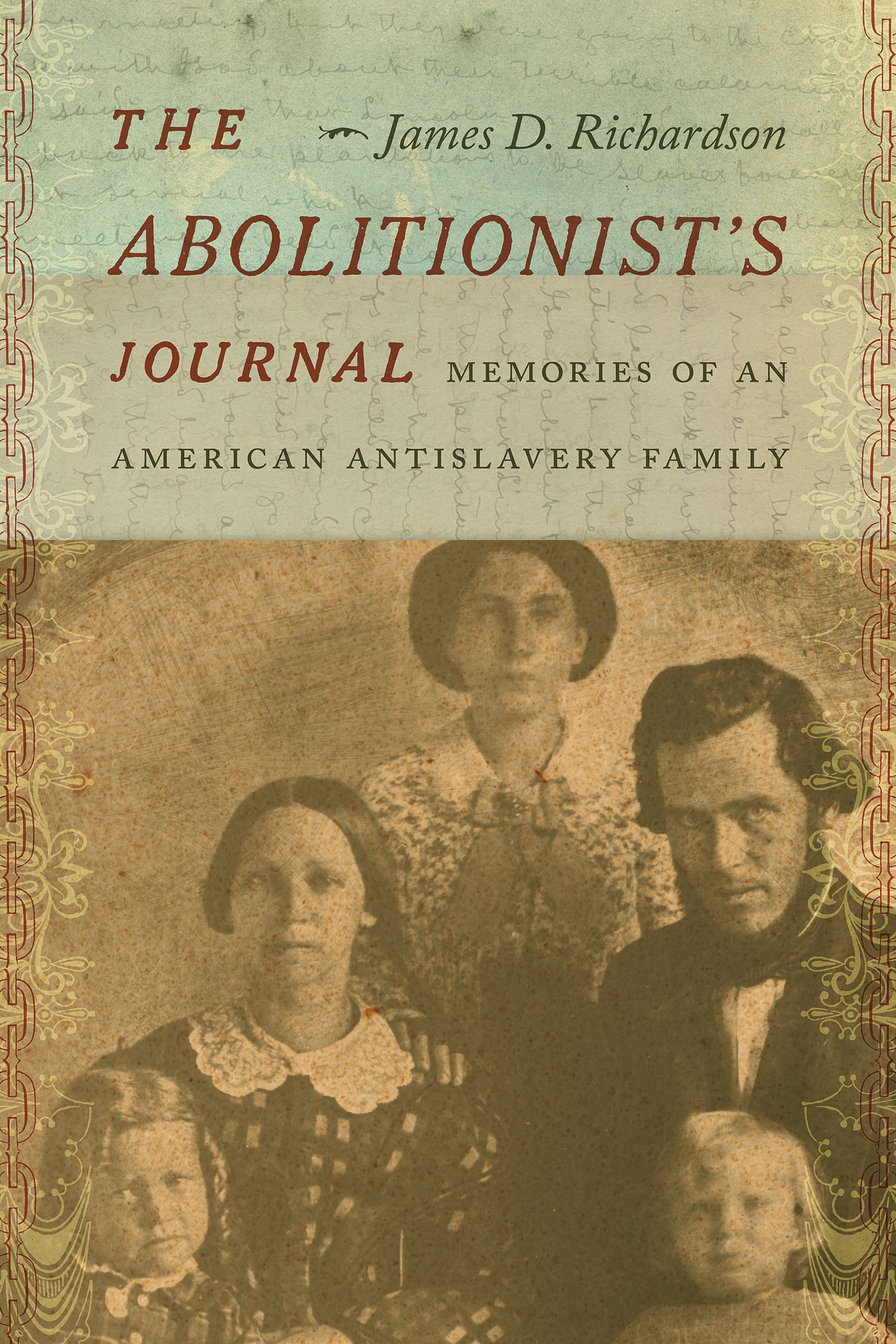

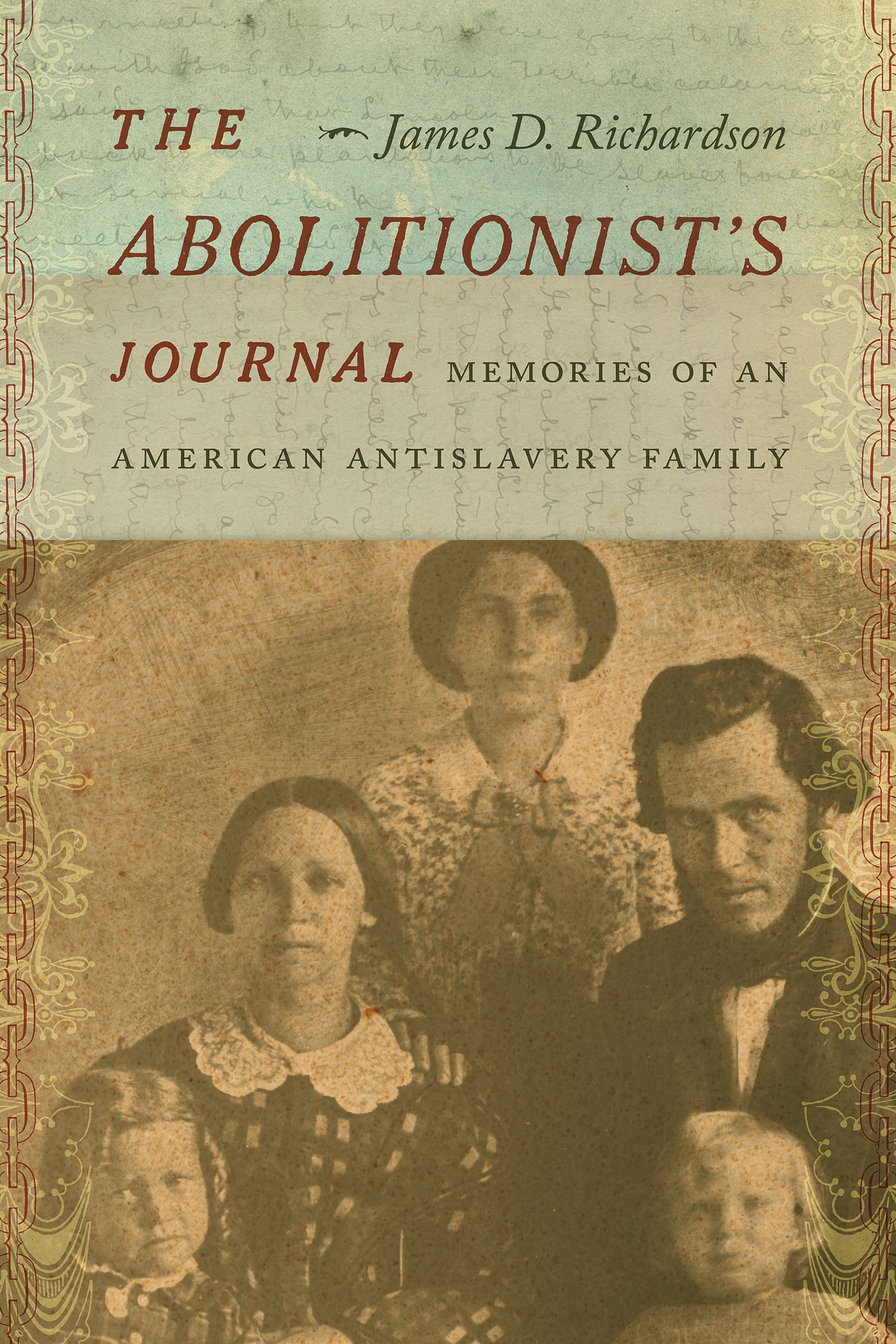

THE ABOLITIONISTS JOURNAL

ALSO BY JAMES D. RICHARDSON | Willie Brown: A Biography

High Road Books is an imprint of the University of New Mexico Press

2022 by James D. Richardson

All rights reserved. Published 2022

Printed in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

NAMES: Richardson, James, 1953 author.

TITLE: The abolitionists journal : the memories of an American antislavery family / James D. Richardson.

DESCRIPTION: Includes bibliographical references and index.

IDENTIFIERS: LCCN 2022013261 (print) | LCCN 2022013262 (e-book) | ISBN 9780826364036 (cloth) | ISBN 9780826364043 (e-book)

SUBJECTS: LCSH: Richardson, George Warren, 18241911. | Richardson, James, 1953 | AbolitionistsUnited StatesBiography. | Antislavery movementsUnited States. | BISAC: BIOGRAPHY & AUTOBIOGRAPHY / Personal Memoirs | SOCIAL SCIENCE / Ethnic Studies / American / African American & Black Studies

Classification: LCC E449.R517 R53 2022 (print) | LCC E449.R517 (ebook) | DDC 326.8092dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022013261

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2022013262

Founded in 1889, the University of New Mexico sits on the traditional homelands of the Pueblo of Sandia. The original peoples of New MexicoPueblo, Navajo, and Apachesince time immemorial have deep connections to the land and have made significant contributions to the broader community statewide. We honor the land itself and those who remain stewards of this land throughout the generations and also acknowledge our committed relationship to Indigenous peoples. We gratefully recognize our history.

DARK TESTAMENT the Pauli Murray Foundation. From Dark Testament and Other Poems by Pauli Murray. Used by permission of Liveright Publishing Corporation. UK/British Commonwealth rights used by permission of the Charlotte Sheedy Literary Agency.

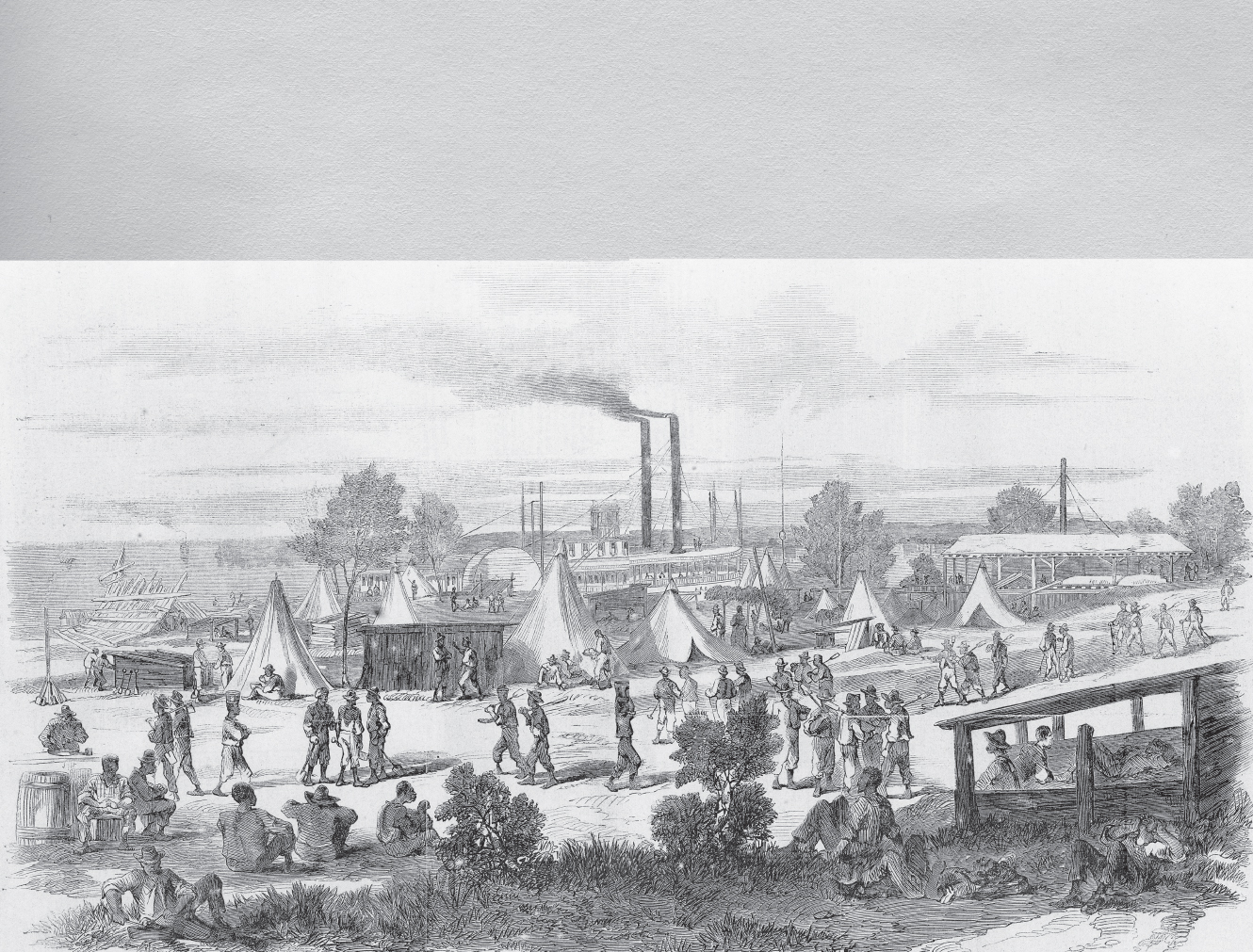

Fort Pickering, Memphis, Tennessee, garrisoned by Black Union soldiers. Sketch by Henri Lovie, appearing in Frank Leslie's Illustrated Newspaper, November 22, 1862.

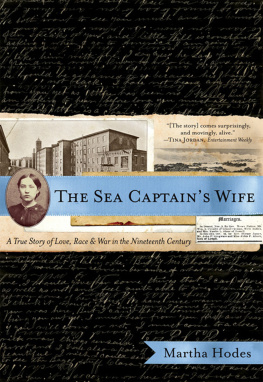

Cover images courtesy of the author | Designed by Mindy Basinger Hill Composed in 10/14 pt Adobe Caslon Pro.

IN LOVING MEMORY of my mother, Jean; my father, David; and his sister, Madge.

AND WITH DEEP ADMIRATION for the courage and perseverance of the Huston-Tillotson University community.

AND FOR LORI who lived this book with me.

He hath sent me to heal the broken-hearted, to preach deliverance to the captives, and recovering of sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised.

THE GOSPEL ACCORDING TO ST. LUKE: IV: 18, from an anonymous Civil War soldiers pocket Bible

CONTENTS

PART I

1

1

THE JOURNAL

Let my vindication come forth from your presence; let your eyes be fixed on justice.

PSALM 17: 2 | BOOK OF COMMON PRAYER

The black, slightly frayed, hardbound notebook sat on my fathers bookshelf for decades. The binding was held together with masking tape, and the pages yellow and fragile. Growing up, I knew very little about the words inside. My father called it simply the journal, and all I knew is it contained the life story of our ancestor, my great-great-grandfather, George. This oversized notebook was my fathers most cherished possession, as he made clear by issuing standing orders that if the house caught fire, the journal was to be evacuated first. My father, David Richardson, was the skipper of a small Navy ship during World War II, and our household was run accordingly.

Looking back, I realize my father knew me better than anyone on earth, and maybe better than I knew myself. He knew exactly when I should read the journal. When I finally didat a pivotal moment in my lifeI wished I had read it years earlier.

Recollections of My Lifework, as our ancestor had formally titled his bookall 334 pages written in neat cursive handwritingdescribes the remarkable tale of George Warren Richardson and his life on the edges of nineteenth-century America. He was born on a farm in New York in 1824, immigrated as a young man to the upper Midwest territories, and became a circuit-riding itinerant Methodist preacher on the prairie frontier.

George and his wife, Carolinehis childhood sweetheartwere ardent antislavery abolitionists. They secretlyand dangerouslyused their home as a stop on the Underground Railroad, spiriting at least one enslaved young woman to freedom, and he recorded how they did it in Recollections of My Lifework.

During the Civil War, George Richardson volunteered as the white chaplain to a colored Union Army regiment posted in Memphis. He saw bloodshed and carnage in Tennessee and Mississippi. After the war, George and Caroline, with two of six their children, founded a college for emancipated slaves that in the twentieth century grew into Huston-Tillotson University in Austin, Texas.

And that is just the start of the remarkable story revealed inside the pages of the journaltales that I knew almost nothing about as a child. It was almost as if our ancestors journal contained a hidden family secret, which in a way it did. Few in our family knew much about George and Caroline Richardson, or their children. My father and his sister Madge were the only people I know who had read his journal. Truthfully, as the decades unfolded into the twentieth century, not everyone who had grafted onto the Richardson family tree and bore his name would have viewed George and Caroline Richardsons work with Black people as heroic or politically correct.

My father gave me the journal in the mid-1990s when I felt the pull to become an Episcopal priest. I had been a newspaper reporter for two decades, covering two presidential campaigns, the 1984 Summer Olympics, the California Legislature, and more murders and criminal trials in Southern California than I can now remember. At the peak of my journalism career, I had written a critically acclaimed biography of Willie Brown, the most powerful politician in California in the 1980s and 90s, and at the time, the most powerful African American politician in the United States. I was at the top of my game as a journalist. But something else stirred within me and would not let go.

After an intense year of conversations with the people closest to me, reading a lot of books, prayers, and meeting with church ordination committees, I was accepted as a postulant for holy orders. I quit my job as a reporter at The Sacramento Bee, collected my vacation pay, and took a monthlong break before entering the Church Divinity School of the Pacific, our Episcopal seminary in Berkeley, California.

With all that preparation, I still had no idea what I was getting into. Leaving journalism for the priesthood was the most radical thing I would ever do and left many of my friends scratching their heads. Truth be told, I wasnt so sure about this either.

PART I

PART I