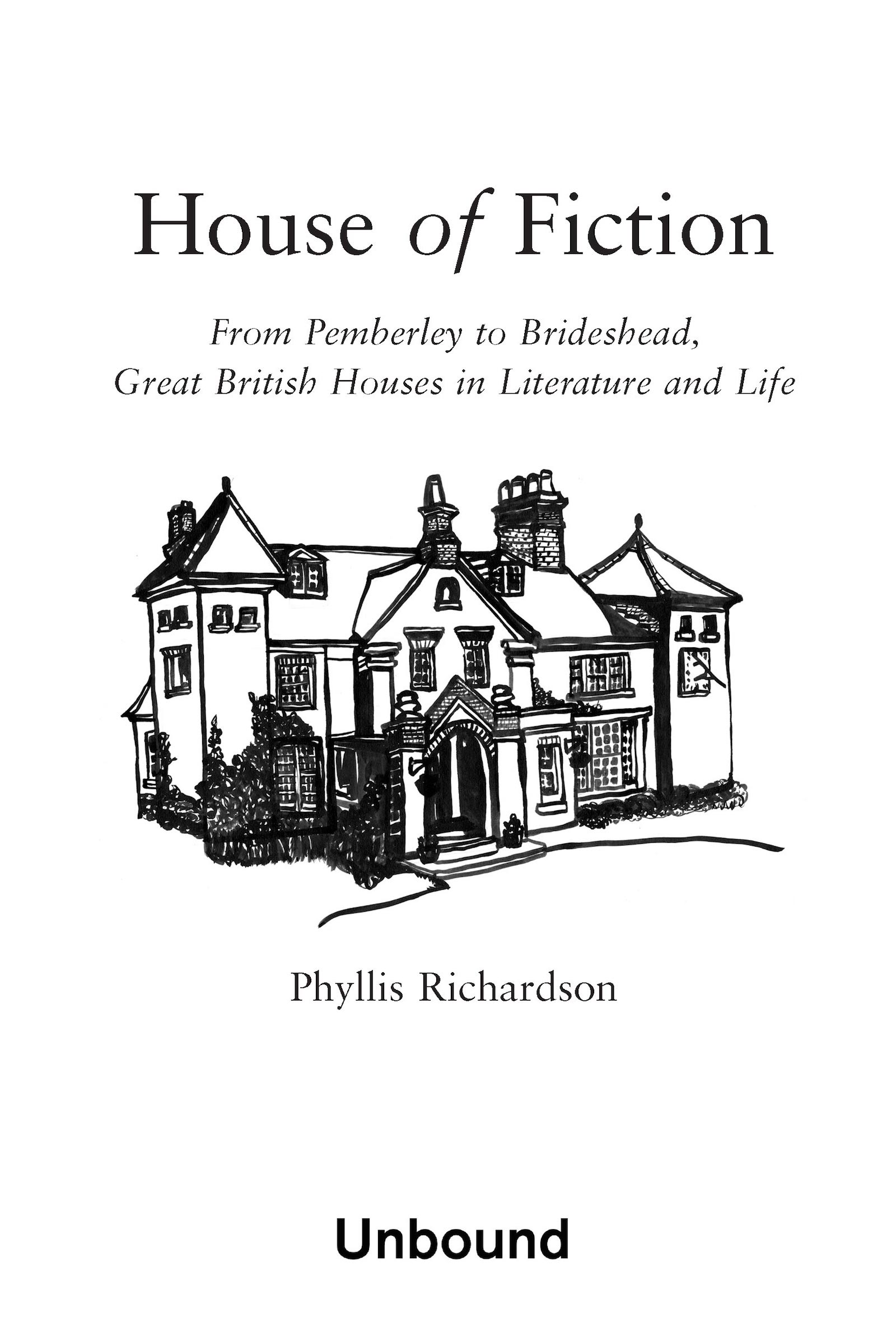

Phyllis Richardson is the author of several books on architecture and design, including the highly successful XS series, Nano House , and Superlight , published in the UK by Thames and Hudson. She has written on architecture, urban development and travel for the Financial Times , the Observer , and DWELL magazine. And she has published many reviews of literary fiction in the TLS and other journals. She is the co-ordinator of the Foundation Year in English and Comparative Literature at Goldsmiths, University of London.

BY THE SAME AUTHOR

Superlight

Nano House

New Sacred Architecture

XS: Big Ideas, Small Buildings

For Lucas, Emile, Mason and Avery

with a pleasure which is both sensual and intellectual we shall watch the artist build his castle of cards and watch the castle of cards become a castle of beautiful steel and glass.

Vladimir Nabokov, Lectures on Literature

Now my aim is clear: I must show that the house is one of the greatest powers of integration for the thoughts, memories and dreams of mankind.

Gaston Bachelard, The Poetics of Space

Dear Reader,

The book you are holding came about in a rather different way to most others. It was funded directly by readers through a new website: Unbound. Unbound is the creation of three writers. We started the company because we believed there had to be a better deal for both writers and readers. On the Unbound website, authors share the ideas for the books they want to write directly with readers. If enough of you support the book by pledging for it in advance, we produce a beautifully bound special subscribers edition and distribute a regular edition and e-book wherever books are sold, in shops and online.

This new way of publishing is actually a very old idea (Samuel Johnson funded his dictionary this way). We re just using the internet to build each writer a network of patrons. At the back of this book, you ll find the names of all the people who made it happen.

Publishing in this way means readers are no longer just passive consumers of the books they buy, and authors are free to write the books they really want. They get a much fairer return too half the profits their books generate, rather than a tiny percentage of the cover price.

If you re not yet a subscriber, we hope that you ll want to join our publishing revolution and have your name listed in one of our books in the future. To get you started, here is a 5 discount on your first pledge. Just visit unbound.com, make your pledge and type HOF5 in the promo code box when you check out.

Thank you for your support,

Dan, Justin and John

Founders, Unbound

Contents

INTRODUCTION

The House of Fictions Many Windows

Why do we enjoy reading about houses? Is it voyeurism, curiosity about how other people live, especially those in grander spaces than our own? Or is it to learn about the past, to get inside not just the rooms but other peoples lives? Why do writers create memorable houses in fiction? Is it to provide a sense of identity, as Walter Scott did in an age when a man was distinguished by the land and house from which he got his name? Or does a house convey ideas of character, as Charles Dickenss minutely detailed residences often reflected the quirks of his multifarious fictional personalities? Do fictional houses offer us meaningful symbols of social status or envy, as with Jane Austens Pemberley, or some tangible link to the past as so ardently forged by writers like Evelyn Waugh?

Houses in fiction do all of these things. In addition, they are sometimes used to draw attention to aesthetic debates. The architecture and art critic John Ruskin comes in for scrutiny in novels by E. M. Forster, Thomas Hardy, Ford Madox Ford and Julian Barnes. He hovers in the background of The Forstye Saga , as Robin Hill and its detractors reflect the controversy over designs for the White House, built in London by the avant-garde architect Edward Godwin for the painter James A. M. Whistler. (Whistler lost the house to debts accrued in suing Ruskin for slander.) Henry James had a particular regard for the artful qualities of the English country house, while John Galsworthy was the first to propose the liberating possibilities of a new style of architecture. However, in the post-war period, that positive vision of modern design was overturned. Social ills engendered by convenience-driven design, and powered by consumer ideals, were brutally depicted by writers such as Anthony Burgess and J. G. Ballard. And the idealistic view of the English country house has been challenged in recent decades by such writers as Kazuo Ishiguro, Ian McEwan and Alan Hollinghurst. If fictional houses have an aesthetic role, they also act as a prism for focusing and diffracting the concerns of the world in which they were built.

The poet Andrew Motion said that It is an extreme form of envy, but the sense of community and hospitality offered by the mead-hall is there in writers from Scott to James to Waugh, as is the destruction at the hand of disgruntled outliers.

It is in the preface to the James carries on at length with the metaphor, which is, of course, not a reference to any actual house. But as Jamess artists all look out from their metaphorical windows, all seeing something different, my focus in this book is on looking in. The houses written about here are both fictional and real, the house of the artist but also that of his or her creation. Many are symbolic, and many serve metaphorical purposes. All help to create atmosphere and work towards communicating an artists notion of time, place, character, society, even spiritual fulfillment, but through an individual vision usually informed by a house the writers knew well and to which they felt some strong connection.

This book is concerned with British authors writing about British houses. Henry James was an American-born writer who became so absorbed in British culture that he took on citizenship of his adopted home. James wrote with particular admiration of the English country house, a setting so prominent in novels as to have inspired its own very British genre, country house fiction. The British may not have the monopoly on house-centred stories, but the literature, from its earliest incarnations, is filled with thinking, writing, and imagining houses in ways that betray a particular consciousness of house and home, and of the cultural and spiritual bonds they represent. They say that an Englishmans home is his castle, that is, the place he rules unequivocally. It could be argued that writers have the same power in the pages of their work and in the houses they build there.

In Tristram Shandy , the confines of the cottage make for the farcical encounters inside, and was probably influenced by the parsonages that Laurence Sterne lived in, particularly the house later dubbed Shandy Hall. Horace Walpole designed all of the Gothic elements of Strawberry Hill along with a group of aesthetically minded friends, and these came to inform the Gothic novel as we know it. The Gothic house was later re-animated by Charlotte Bront, Charles Dickens, Daphne du Maurier and Agatha Christie from houses they experienced; some were objects of personal obsession. Walter Scott built his beloved home, Abbotsford, in the Scottish Baronial style, which reflected the kinds of manorial houses that are key to many of his romatic tales, but also symbolised his own desire to inhabit the role of Scottish laird. Jane Austen led us through the drawing rooms and tea tables of Regency England and showed us the trend for improving houses and gardens, all the while whispering in our ears about how the laws of property were so unjust to women. Thomas Hardy was an architect before he became a writer, helping to restore many a Gothic church, building schools and eventually his own house. E. M. Forsters father was an architect too and built the last house that the writer truly loved, a relationship he channelled into his lyrical rendering of the eponymous cottage in Howards End .

Next page