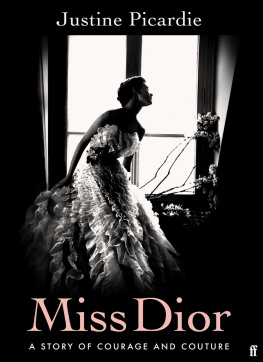

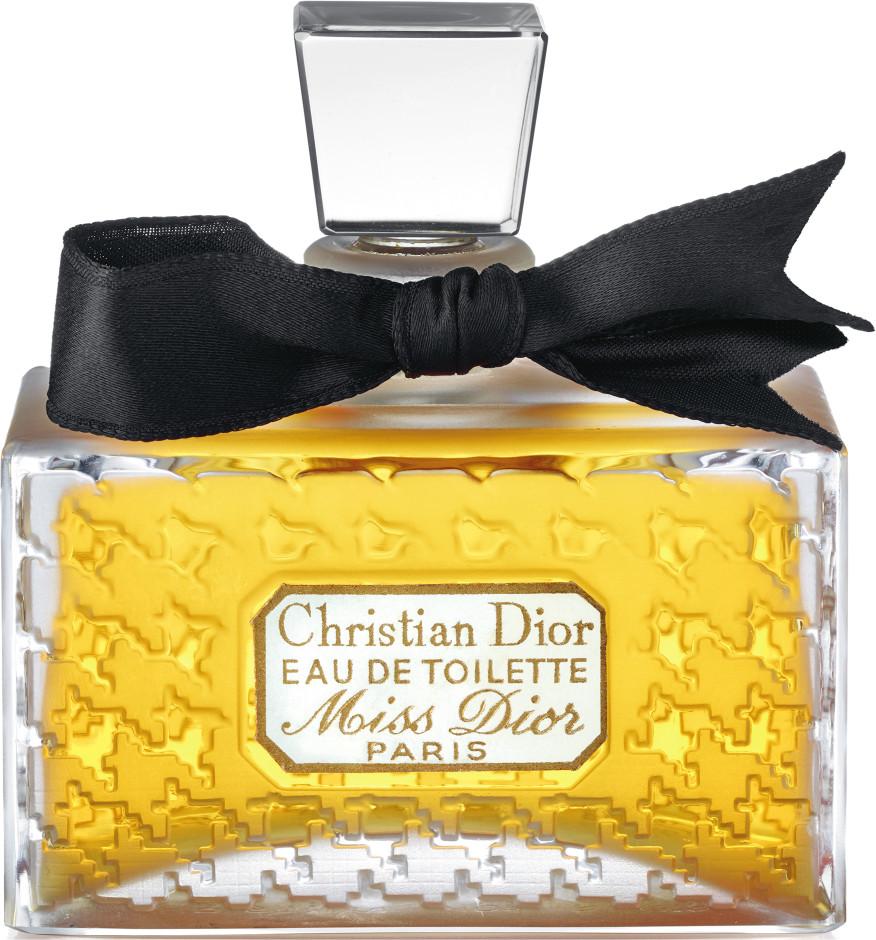

For four years, we worked, we searched, like alchemists in pursuit of the philosophers stone. And then Miss Dior was born

Because, you see, for a perfume to hold, it must first be held for a long time in the hearts of those who created it.

This is the story of a ghost who walked into my life on a sunlit Sunday morning in early summer, and would not let go of me, however much I might wish, at times, to be free of her. Her name is Catherine Dior, and she arrived as I wandered through the garden of La Colle Noire, her brother Christians graceful chteau in the hills of rural Provence; a place she often visited, and a house where she lived for a while, after his sudden death of a heart attack at the age of fifty-two, in 1957.

Catherine was twelve years younger than Christian he was born in 1905, the second son of a prosperous family; she was the youngest of five children, born in 1917, just before their eldest brother, Raymond, began his service in the French army during the First World War. But thoughts of war were far from my mind during that enchanting day at La Colle Noire. Instead, I was seduced by the exquisite beauty of the house, bought and restored by Christian Dior with the proceeds of the successful brand that he had created in 1946.

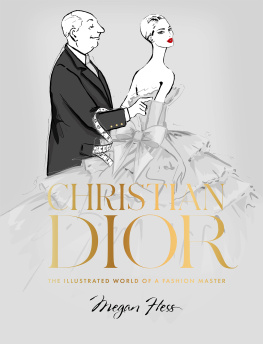

His debut collection, shown in Paris on 12 February 1947, had been christened the New Look by Carmel Snow, the editor of Harpers Bazaar (a position that I, too, have been privileged to hold). But despite the name, it was as much a nostalgic reimagining of the Belle Epoque, the golden years before the Great War. This was the era of Christians early childhood, growing up in the secure surroundings of the Dior family home in Granville, on the coast of Normandy. His mother, Madeleine, had dressed in the romantic, sweeping gowns of the period, and it was these that inspired Diors creation of swishing full skirts and a rounded hourglass silhouette, achieved with a corseted waist and padded bust. Yet equally important to Diors conception of flower-like women that emerged in his couture salon in Paris was his mothers love of gardening. Madeleines passion which she passed on to Christian and Catherine had found expression in the expansive garden she established at Granville, a miracle of hope and desire, built on a rocky outcrop overlooking the churning sea, several hundred feet below.

Her husband, Maurice Dior, had inherited the family fertiliser business, and on days when the wind was blowing in the wrong direction, the stench of his factories would drift across the town, although seldom as far as Les Rhumbs. But for all its unsavoury connotations, the guano industry paid for Madeleines magical creation on a barren cliff top: tender flowerbeds protected from the salt-laden storms by hardy conifer trees, and most importantly of all, the roses that were (and remain) the centrepiece of the garden.

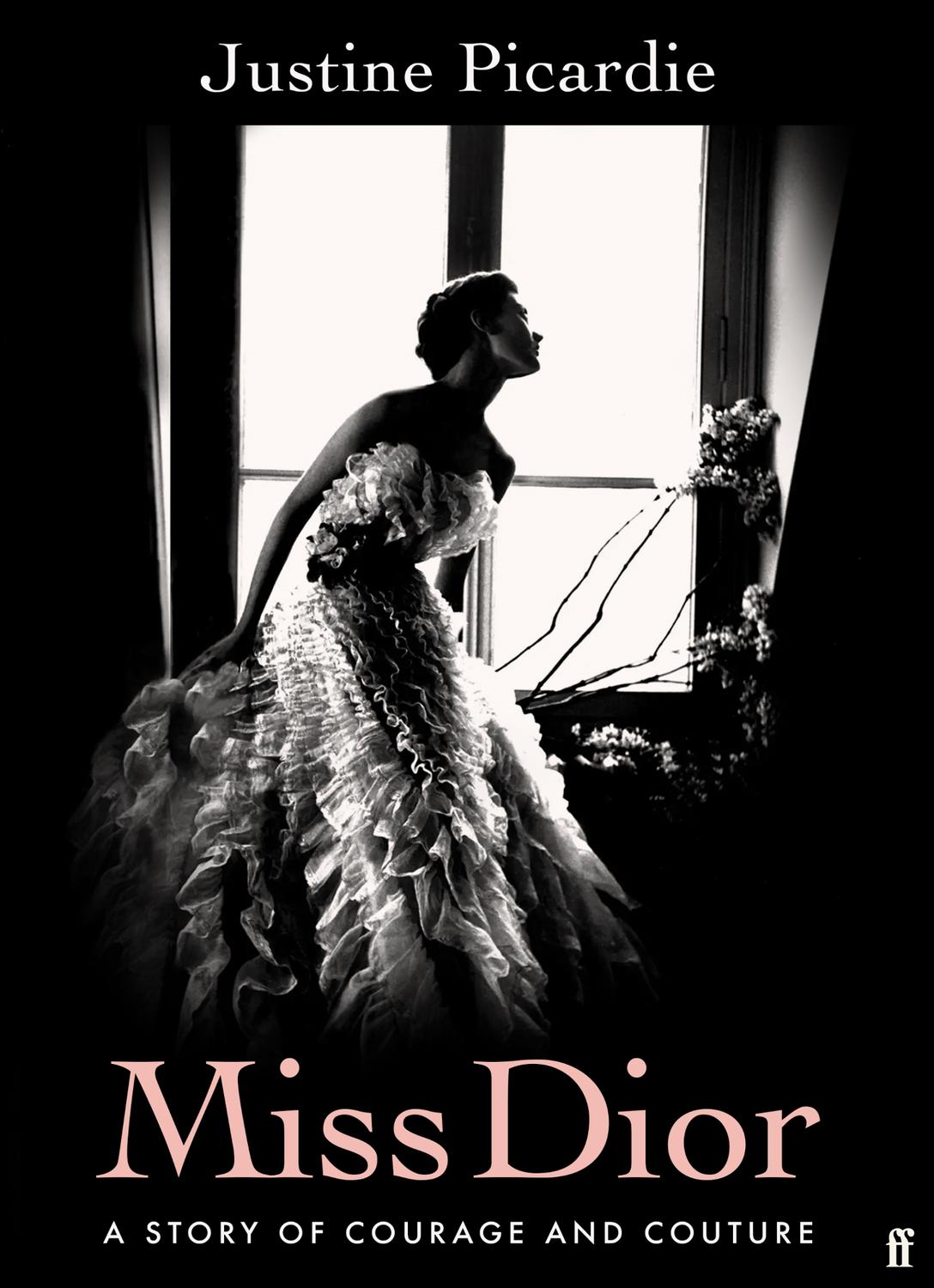

Roses continue to bloom everywhere at La Colle Noire, too: tumbling over pergolas and climbing up the outside walls, their tendrils gently tapping at the windows; luxuriant even on the patterned floral wallpaper and chintz furnishings within. And beyond the terraces and herbaceous borders is a meadow of a thousand rose bushes, whose flowers are still gathered (just as they have been since the field was planted to Christian Diors original specifications) to produce an essential ingredient for his perfumes. The first of these, and closest to Christians heart, was launched alongside the New Look collection, and named in honour of his beloved sister Catherine: Miss Dior.

Catherine outlived her brother by five decades, and died in June 2008, not far from La Colle Noire, at her home in the neighbouring village of Callian. Here she too cultivated roses, both for her own pleasure and to be distilled as an essence for Diors perfume manufacturers in nearby Grasse. She had been a loyal and loving sister throughout her brothers life, and continued to be so after his death, honouring his legacy in many ways, including her consistent support for the Christian Dior museum that was eventually established in Granville.

But while Christian became one of the most famous Frenchmen in the world a celebrated name alongside Charles de Gaulle the remarkable story of Catherine Dior has never been fully explored. The little I knew of her life I had gathered from the Dior archives before I first visited La Colle Noire: she had lived with Christian in Paris in the late 1930s, and shared a small farm with him during the war, on the outskirts of Callian, where they grew vegetables, as well as roses and jasmine. Then she joined the French Resistance, and was captured by the Gestapo, before being deported to Ravensbrck, a German concentration camp for women.

One of the Dior archivists, Vincent Leret, had come to meet me at La Colle Noire on this particular Sunday morning, to discuss the possibility of me writing a new biography of Christian Dior. Yet as we spoke, I found myself asking him more and more questions about the mysterious Catherine, who appeared to have rarely referred to her involvement in the Resistance, nor her time in Germany. Vincent had known Catherine before moving to his job at the Dior archives in Paris, he worked for the museum in Granville and they corresponded, whenever he had queries that she could answer about her brother. But she gave nothing away of her wartime experiences, and he said that he felt it would have been impolite to press her for more information. As for the other writers who had previously chronicled the life of Christian Dior, few were particularly interested in Catherine, or even aware of her deportation to Ravensbrck. It was as if the hermetic world of haute couture had no concern for a woman such as Catherine Dior, or for the suffering that she had endured; nor even as to whether her experiences had played a part in her brothers legendary vision of fashion and femininity.

I wrote some notes, and then walked down to the meadow of roses, where butterflies danced about the petals, accompanied by a chorus of birdsong and bees. All was peaceful, caressed by gentle sunlight; yet as I stood there, I wished with all my heart that I had met Catherine before her death, a decade previously. And it was then, in that instant, that the seed was sown within me; a desire more akin to obsession even possession that I would tell the story of this silent woman and her unknown comrades, who had somehow survived Ravensbrck and returned to France; but to a France where many of their compatriots preferred simply to forget the war years and disregard the shame of collaboration.