Contents

Guide

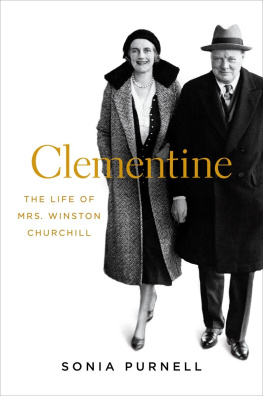

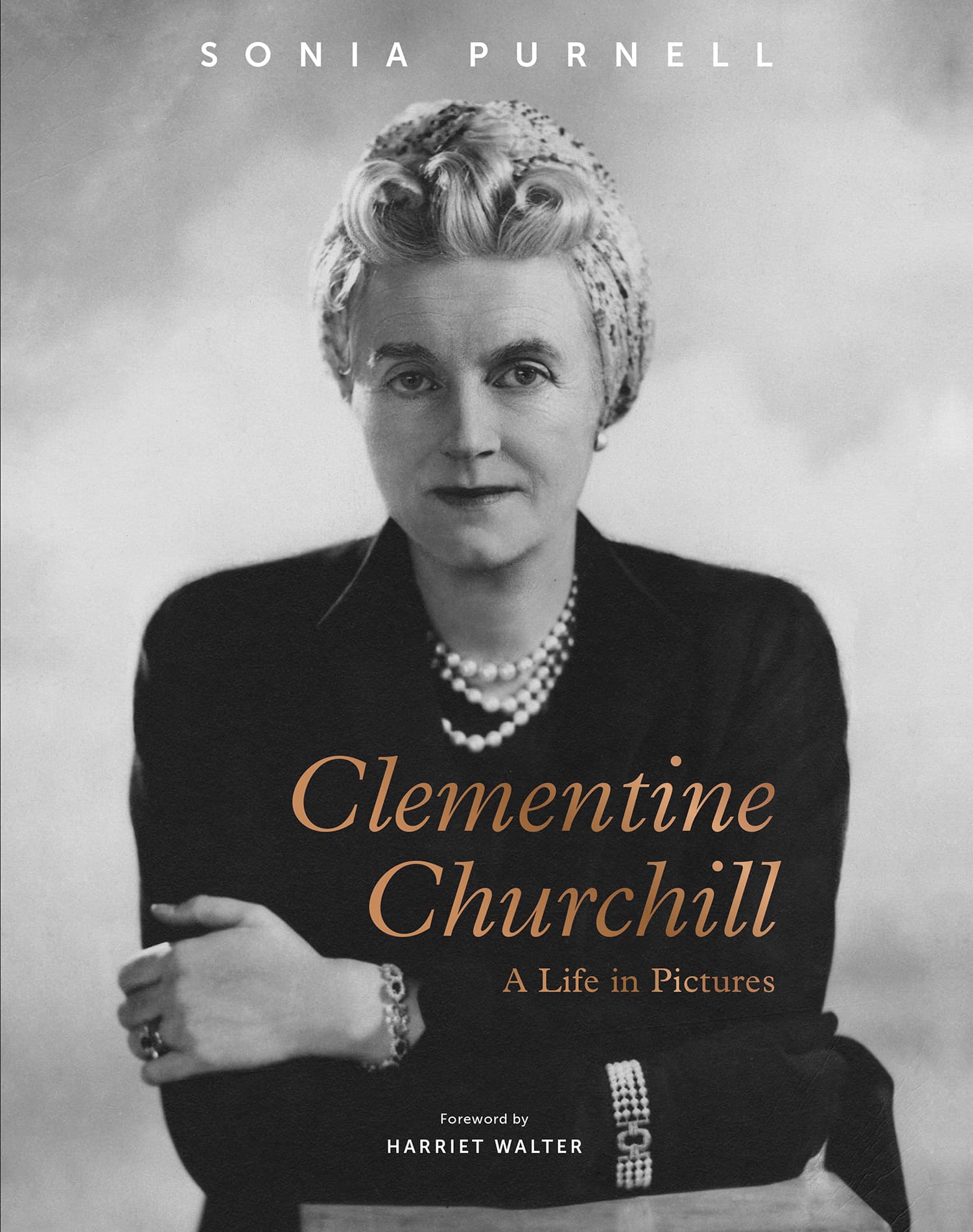

SONIA PURNELL

Clementine Churchill

A Life in Pictures

For Jon, Laurie and Joe

With all my love

I send this token, but how little can it express my gratitude to you for making my life & any work I have done possible, and for giving me so much happiness in a world of accident & storm.

Winston to Clementine, on their fortieth wedding anniversary, 12 September 1948, Cap dAntibes

FOREWORD

I was already midway into playing Clemmie in the television series The Crown when this wonderful biography came out and it was like a whirlwind of fresh air to me, a door being opened from a tiny crack into a flood of sunlight. I had already soaked up everything that Mary Soames had written about her mother and the letters between her parents, and I had tried to get behind the eyes in the public face that looked out at me from Clemmies photos. I was brimful of her but I knew I would have to hold back so much. In The Crown, as in life, Clemmie would be seen as a supporting role.

Sonia Purnell gets behind the supporting role and puts Clementine Churchill at the heart of the story. Most male-centred history books are only interested in women for the light they may throw on the Great Man, as the power behind the throne. For me, Clementine was not so much behind Churchill as alongside him, supplying fortitude when his own failed, sensitivity when he lacked it, often disagreeing with him privately but always supporting him publicly. Sonia Purnell confirmed me in that view and has placed in the public domain everything I was struggling to communicate in a small corner of the small screen.

One thing I did manage to influence as a result of reading First Lady, was the filming of the destruction of Graham Sutherlands portrait of Churchill. Clemmie wanted rid of the object that caused her husband so much distress, and in the original script she silently looked on as a removal man smashed the painting to smithereens with a mallet. Luckily, we hadnt shot the scene yet and when I found out the true story in this book (see and became one of the most memorable visual sequences in the whole series. I shant spoil it here. I will just say that flames supplanted the mallet. I am proud to have been a link in that chain of information.

What struck me above all about the incident was that Clemmie had told her private secretary that no one need know what had happened. She said this mainly to protect her staff from blame, but for me it also pinpointed the habit of mind of that generation and class. It is a combination of what we do is no one elses business and the wartime expediency of information being restricted on a need to know basis.

But it also exemplifies the tantalising reticence of women in general and in particular of Clementine Churchill, who never wanted to be publicly known. Dont worry, Clemmie, we realise that no one book or performance can ever sum up a life, but we hope you understand that with so many millions of words written by and about your husband, we have a great need to know more about you.

Harriet Walter

INTRODUCTION

L ate on the evening of Monday 5 June 1944, Clementine Churchill walked past the Royal Marine guards into the Downing Street Map Room. Wearing an elegant silken housecoat that covered her nightdress, her beautiful face still fully made up, she looked immaculate and, as always, serene. Around her, though, the atmosphere in the heart of British military command was palpably tense, even frayed. She glanced at the team of grave-faced plotters busily tracking troops, trucks and ships on their charts. Then she cast her eyes over the long central table, from which the phones never stopped ringing, to the far corner where, as she expected, she spotted Winston, shoulders hunched, jowly face cast in agonised brooding. She went to him as she knew she must, for no one else, no aide, no general, no friend however loyal, could help him now.

Clementine was one of a tiny group privy to the months and years of top-secret preparations for the next mornings monumental endeavour. Fully apprised of the risks of what would be the largest seaborne invasion in history, she knew, too, the unthinkable price of failure: millions of people and a vast swathe of Europe would remain under Nazi tyranny, their hopes of salvation dashed. Uniquely, however, she also understood the ghosts that haunted Winston that night, thinking as he was of the thousands of men he had sent to their deaths in the Dardanelles campaign of the First World War. She alone had sustained him both through that disaster and the horrors of his time serving in the trenches on the Western Front. Now, tens of thousands more were to risk their lives in northern France. Huge convoys were already moving through the darkness towards their battle stations off the coast of Normandy. He had delayed the D-Day operation for as long as he could to ensure the greatest chance of success, but now British, American and Canadian troops would, in a few hours, attempt to take a heavily fortified coastline defended by what were regarded as the worlds best soldiers.

Earlier that evening, Winston and Clementine had discussed the prospects of the gambits success again, at length and alone over a candlelit dinner. No doubt he had poured out his fears and she had sought, as so many times before, to stiffen his resolve. Yet it could be put off no longer; the command to proceed had been given. Raising his face as she approached, Winston turned to his wife and asked, rhetorically: Do you realise that by the time you wake up in the morning, twenty thousand men may have been killed?

To the outside world Winston Churchill showed neither doubt nor weakness. Since he had declared to the world in June 1940 that Britain would never surrender, his had become the voice of defiance, strength and valour. Even Stalin, one of Winstons fiercest critics, was to concede that he could think of no other instance in history when the future of the world had so depended on the courage of a single man. But what enabled this extraordinary figure to stand up to Hitler when others all around him were crumbling? How did he find in himself the strength to command men to go to their certain deaths? How could an ailing heavy drinker and cigar-smoker well into his sixties carry such a burden for five long years while cementing an unlikely coalition of allies that not only saved Britain, but ultimately defeated the Axis?

Winstons conviction, his doctor Lord Moran observed while tending him through the war, began in his own bedroom. This national saviour and global legend was in some ways a man like any other; he was not an emotional island devoid of the need for personal sustenance, as so many historians have depicted him. His resolve drew on someone elses. In fact, Winstons upbringing and temperament made him almost vampiric in his hunger for the love and energy of others. Violet Asquith, who adored him all her life, noted that he was armed to the teeth for lifes encounter but also strangely vulnerable and in want of protection.

Only one person was able and willing to provide that protection whatever the challenge, as she showed on that critical June night in 1944. Yet Clementines role as Winstons wife, closest adviser and greatest influence was overlooked for much of her life, and has been largely forgotten in the decades since.