Copyright 2022 by Esther Zuckerman

Interior and cover illustrations copyright 2022 by Montana Forbes

Cover copyright 2022 by Hachette Book Group, Inc.

Hachette Book Group supports the right to free expression and the value of copyright. The purpose of copyright is to encourage writers and artists to produce the creative works that enrich our culture.

The scanning, uploading, and distribution of this book without permission is a theft of the authors intellectual property. If you would like permission to use material from the book (other than for review purposes), please contact permissions@hbgusa.com. Thank you for your support of the authors rights.

Running Press

Hachette Book Group

1290 Avenue of the Americas, New York, NY 10104

www.runningpress.com

@Running_Press

First Edition: February 2022

Published by Running Press, an imprint of Perseus Books, LLC, a subsidiary of Hachette Book Group, Inc. The Running Press name and logo is a trademark of the Hachette Book Group.

The Hachette Speakers Bureau provides a wide range of authors for speaking events. To find out more, go to www.hachettespeakersbureau.com or call (866) 376-6591.

The publisher is not responsible for websites (or their content) that are not owned by the publisher.

graphic from Getty Images contributer carduus/DigitalVision Vectors

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021943384

ISBNs: 978-0-7624-7550-6 (hardcover), 978-0-7624-7549-0 (ebook)

E3-20211203-JV-NF-ORI

O VER THE COURSE OF NEARLY 100 YEARS, THE rituals of the Academy Awards and its attire have been chronicled and codified. A certain level of glam in ones presentation is expected, if not demanded, and now supported by a cottage industry of stylists and squads who are at the beck and call of nominees and presenters to turn them from mere mortals into gods and goddesses. For those of us at home on our couches, there are traditions too: Turning on E! in the middle of the day to watch the hours-long red carpet coverage before switching to the official telecast; logging onto Getty Images to get a closer look at the detailing on the gowns; reading websites like The Fug Girls or Tom and Lorenzo the next day for expert analysis of the fashion.

The Oscars have often been written off as a frivolous, out-of-touch, navel-gazing celebration of Hollywood by Hollywood, but for better or worse they have become a pop culture bellwether, as much for their spectacle as for their substance. Only some of the most memorable Oscar moments have anything to do with the movies in contention. And many have more to do with clothes than anything else. For every Moonlight beats La La Land shocker, theres a Bjrk swan dress.

Fashion and the Oscars have become inextricably linked, particularly for the women who attend the event, but theres more to the question who are you wearing? than is commonly assumed. What a woman chooses to put on her body for arguably the highest-profile event of the year can be a statement of intent, an acceptance of status in the pantheon of celebrity, or a rebuke of the role shes been assigned. Her pick carries a lot of weight. If she wins, that can be the image of her that lands in the history books. It matters.

Talking about fashion devoid of context can be tricky. In 2015, the #AskHerMore campaign began as an effort to get commentators to stop asking women at the Oscars and other awards shows substance-free questions solely about their clothing. But, even though reporting on red carpets is often fizzy (and occasionally even demeaning), the substance of the fashion is not. Style is a statement, and Oscar-wear especially speaks volumes, whether youre Joan Crawford accepting a trophy in a nightgown from bed or Edy Williams baring as much as possible on the pathway to the Dorothy Chandler Pavilion.

You cant talk about the Oscars without talking about politics: After all, the notorious MGM studio head Louis B. Mayer invented the Academy as a way to stop the formation of unions among Hollywoods workers in the late 1920s. His notion was that if he established this organization to celebrate the stars and artisans of the studio system, they wouldnt ask for rights and benefits from their bosses. His ploy didnt work, but the Oscars did, and became a cause for celebration and an arbiter of the industrys status quo. Its not as if the Oscars celebrate the most daring films released every year. They often uphold old-fashioned ideas of what Hollywood is supposed to look like: white, wealthy, and unadventurous.

In the early days Oscar fashion was often dictated by studios. The honored women would wear outfits by the costume designers who had dressed them for their films. Couture started to enter the conversation by the 1950s and 60s, and by the 1990s, when Joan and Melissa Rivers began their reign of comedic terror over on E!, the business of who was wearing what was as much of an industry as the awards themselves. Joan Rivers showed up, Who did your dress? And before you know it all the European designers were offering clothes for nothing, which always made me laugh, the legendary designer Bob Mackie told me in an interview for this book. Here are these people making millions of dollars being in movies: They love to get a free dress.

The Rivers era was marked by nastiness. Make what they considered to be an ill-advised sartorial decision and you would get mercilessly mocked. In a 2016 piece for the New York Times, the writer Haley Mlotek issued a searing takedown of carpet culture. Red-carpet commentators enforce a code of conduct that pretends to be about fashion but is really about control, she wrote. Appointed by television networks and glossy magazines, these people dont reward self-expression. Theyre implementing a now-entrenched notion of what makes a winning red-carpet dress: a glorified prom dress with a couture tag.

Hollywoods reckoning following the #MeToo movement has seemingly ushered in an age of commentary that is, at least on its surface, less cruelly critical of women and their choices, regarding fashion or otherwise. In an age of positivity online, worst-dressed lists dont hold the same cache as they once did. Outfits that were once derided have received waves of reappraisals. Extravagance is cheered rather than admonished.

But the Oscars these days are known as much for their sparkles as they are for their sins, whether nasty sexism or the racism implicit in the overwhelming whiteness of the winners. April Reign was watching the nominations in 2015 when she tweeted #OscarsSoWhite, a hashtag that evolved into a movement thats still ongoing. To combat the long-entrenched racism of the institution, the Academy began attempting to expand its membership. And, yet, a retrograde movie like Green Book still won Best Picture in 2019, making the case that the younger, more diverse membership hadnt made much of an impact yet.

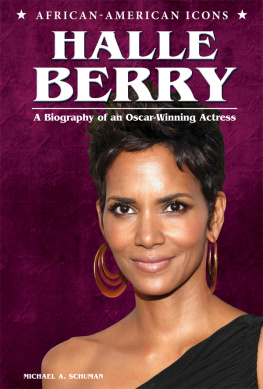

This is all to say, if you look at Oscar style in a bubble, youre missing the bigger picture. Gowns are often so much more than just gowns. And frequently they arent even gowns. (Some of the women I write about in this book opted for pants.) These ensembles, arranged chronologically, offer insight into the women they adorn and the world they occupy. Mary Pickfords jeweled drop-waist signals a woman who was about to mold what would become a Hollywood tradition in her own image. Rita Moreno obtained her patterned dress at a low point in her life and proved she was still standing when she donned it decades later. Jane Fondas black suit in 1972 echoed her activism. Diablo Codys leopard-print sheath kept true to her riot grrrl spirit. Zendaya boldly wore locs and was met with uninformed criticism, but both her look and her response to the naysayers heralded the arrival of a new star. There are the most famous pieces of Oscar attire, of courseAudrey Hepburns white quasi-Givenchy and Halle Berrys embroidered Elie Saabbut there are also others that nonetheless have their own strange, fascinating narratives even if they arent as immediately recognizable. And through the lens of Oscar fashion, you can also examine the racism and sexism that has plagued Hollywood since its birth.