Contents

Landmarks

Print Page List

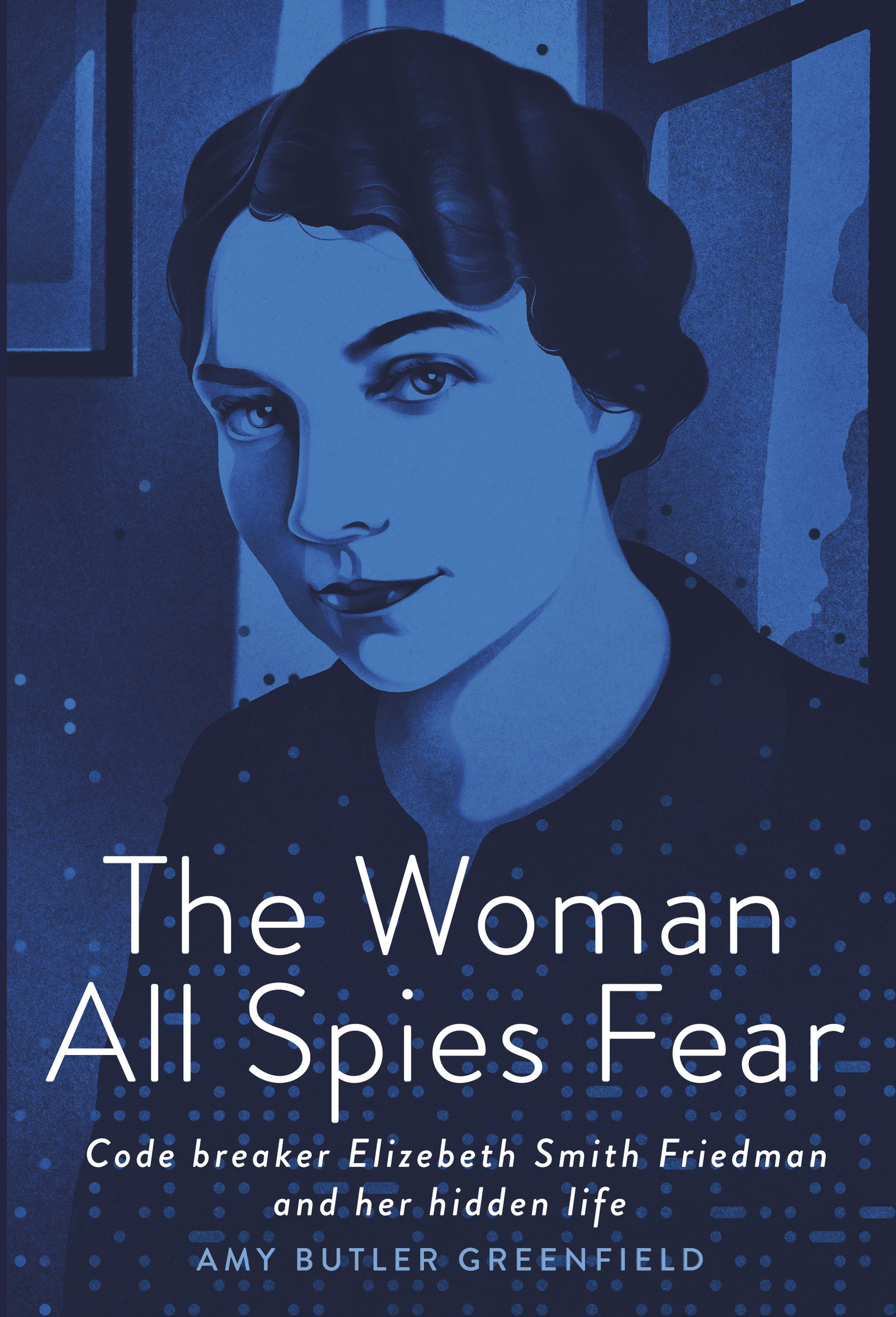

Text copyright 2021 by Amy Butler Greenfield

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Random House Studio, an imprint of Random House Childrens Books, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York.

Random House Studio and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Visit us on the Web! rhcbooks.com

Educators and librarians, for a variety of teaching tools, visit us at RHTeachersLibrarians.com

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Name: Greenfield, Amy Butler, author.

Title: The woman all spies fear : code breaker Elizebeth Smith Friedman and her hidden life / Amy Butler Greenfield.

Description: New York : Random House Studio, [2021] | Includes bibliographical references. | Audience: Ages 12+ | Audience: Grades 79 | Summary: Biography of Elizebeth Smith Friedman, an American woman who pioneered codebreaking in WWI and WWII but was only recently recognized for her extraordinary contributions to the fieldProvided by publisher.

Identifiers: LCCN 2021009061 (print) | LCCN 2021009062 (ebook) | ISBN 978-0-593-12719-3 (hardcover) | ISBN 978-0-593-12720-9 (lib. bdg.) | ISBN 978-0-593-12721-6 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Friedman, Elizebeth, 18921980Juvenile literature. | CryptographersUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. | Friedman, William F. (William Frederick), 18911969Juvenile literature. | CryptographersUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature. | CryptographyUnited StatesHistory20th centuryJuvenile literature. | World War, 19391945Participation, FemaleJuvenile literature. | World War, 19141918Participation, FemaleJuvenile literature. | Married peopleUnited StatesBiographyJuvenile literature.

Classification: LCC D639.C75 G74 2021 (print) | LCC D639.C75 (ebook) | DDC 940.54/8673092 [B]dc23

Ebook ISBN9780593127216

Random House Childrens Books supports the First Amendment and celebrates the right to read.

Penguin Random House LLC supports copyright. Copyright fuels creativity, encourages diverse voices, promotes free speech, and creates a vibrant culture. Thank you for buying an authorized edition of this book and for complying with copyright laws by not reproducing, scanning, or distributing any part in any form without permission. You are supporting writers and allowing Penguin Random House to publish books for every reader.

ep_prh_5.8.0_c0_r0

For Jenny Turner,

a strong woman and a true friend

Contents

In 1942, in the middle of World War II, some strange letters came to the attention of the Federal Bureau of Investigation. They were all addressed to the same person in Argentina, and they all sounded oddly alike, yet they came from four different American women. The letters were about dolls, and they ran like this:

I have been so very busy these days, this is the first time I have been over to Seattle for weeks. I came over today to meet my son who is here from Portland on business and to get my little granddaughters doll repaired. I must tell you this amusing story, the wife of an important business associate gave her an Old German bisque Doll dressed in a Hulu Grass skirt

When the FBI questioned the women who supposedly had sent the letters, the women knew nothing about them. FBI lab experts confirmed that the womens signatures were excellent forgeries.

Someone knew these women well enough to fake their handwriting. Someone was hiding behind their names. Could it be a spy?

The FBI kept digging for clues. The four women lived in different cities and didnt know each other, but it turned out they had something in common. All of them were long-distance customers of a doll shop at 718 Madison Avenue in New York City.

The FBI checked out the shop. Filled with pricey dolls in fancy costumes, it didnt look like the headquarters of a spy ring. The shops owner, Velvalee Dickinson, appeared innocent, too. A graduate of Stanford University, she was a fifty-year-old widow who had been in the doll business since 1937. She and her late husband had once been friends with many Japanese officials, but that was before Japan and the United States had gone to war.

The FBI remained leery. They staked out the doll shop, and they examined Dickinsons bank account and safe-deposit box. In January 1944, after they traced some of her money back to Japanese sources, they arrested her as a spy.

Dickinson fought back. Tiny, dark-haired, and delicate, she screamed and kicked, scratching at the FBI agents like a wildcat. When they questioned her, she insisted the money had nothing to do with spies. It came from her doll business and insurance payouts.

The FBI was worried. While theyd been able to connect Dickinson to the letters, they werent sure how to interpret them. The money trail was also murky, with no clear proof of a link to spymasters. Everything was guesswork, which wouldnt impress anyone when the case went to trial.

One of the lawyers who had to prosecute the case was assistant U.S. attorney Edward Wallace. He had plenty of courtroom experience, and he knew it was time to seek help. He also knew exactly who he wanted to approachone of Americas top code breakers, Elizebeth Smith Friedman.

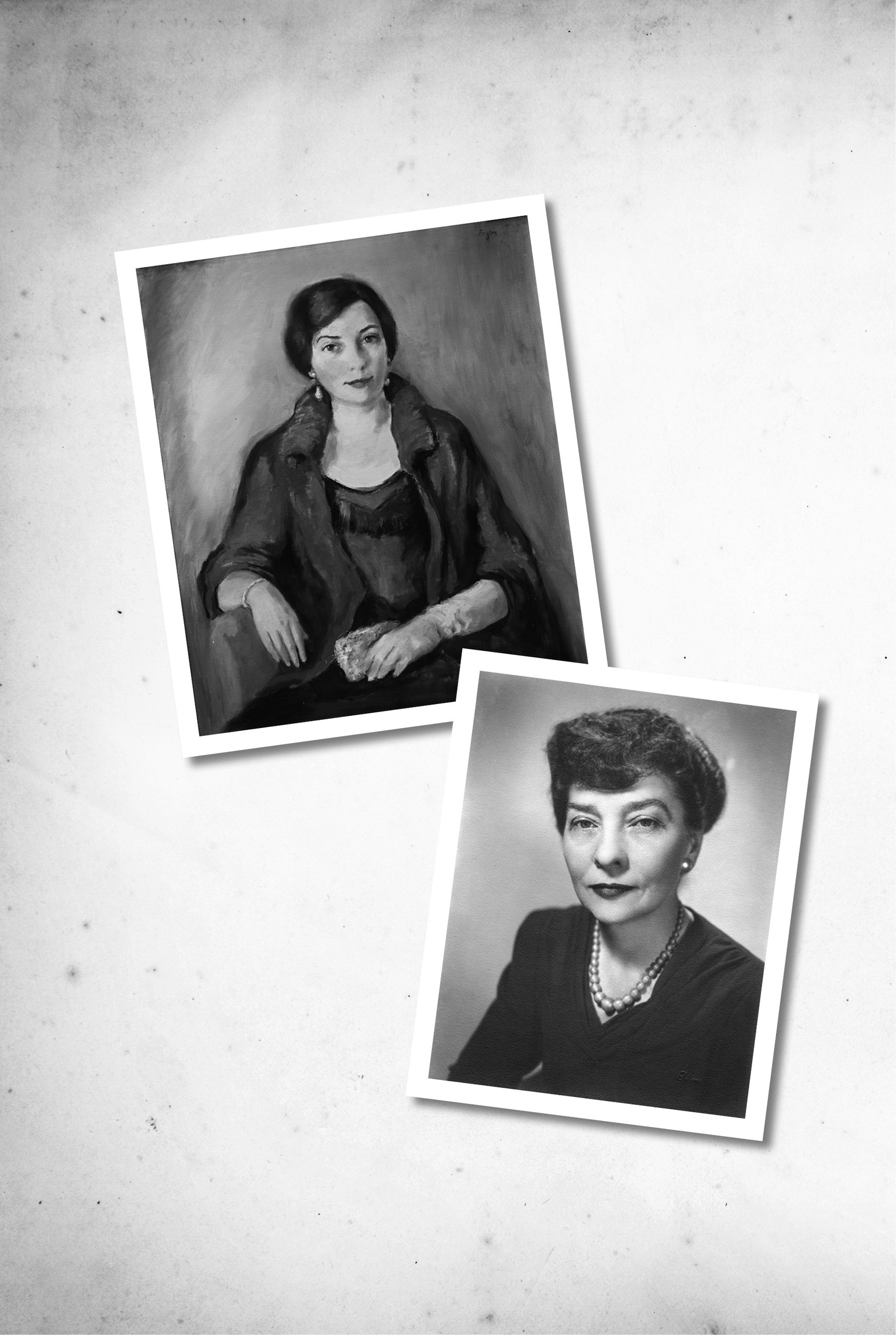

Like Dickinson, Elizebeth was also small, dark-haired, and college-educated, but the resemblance ended there. As a young woman, she had played a key role in code breaking during World War I. She later cracked the codes of American mobsters, smashing their crime gangs. Now, in 1944, she had a top-secret job at the Navy.

Wallace believed that if anyone could crack the Doll Woman letters, it was Elizebeth. But when he asked the FBI if he could put her onto the case, the FBI balked. It wasnt that they doubted her skill. They had worked with her many times before, so they knew just how good she was. As they saw it, the problem was that Elizebeth was too good. They couldnt stand the thought that the credit for catching Dickinson might go to her, and not to the FBI.

When it came down to it, however, the FBI needed a conviction. After an initial protest, they allowed Wallace to share the Doll Woman letters with Elizebeth. Luckily for them, the Navy wanted her skills to remain secret, so her name had to be kept out of the record. In case documents, she would be called Confidential Informant T4.

Although Elizebeth was busy tracking Nazi spies, she made time to look at the Doll Woman letters. At first, she was given very little background to go on, but even so, she made progress. Soon she was startling everyone with her insights.

As she explained to Wallace, the letters were written in what was called open code. This meant that ordinary sentences and phrases had been given secret meanings, agreed upon in advance. These phrases were then strung together in ways that made the letter seem more or less natural to a casual reader.

Elizebeth warned Wallace that the precise meaning of this kind of code was hard to prove. There was usually a certain amount of guesswork involved, and that would make the case a challenge to prosecute. Yet her analysis was shrewd and hard-hitting.