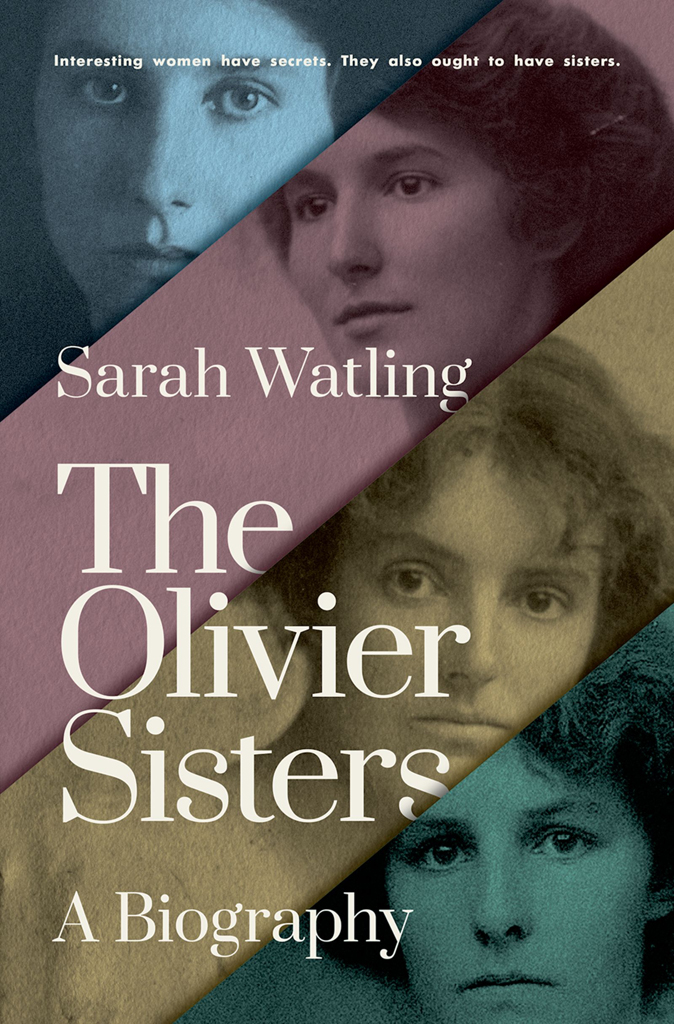

The Olivier Sisters

The Olivier Sisters

A Biography

SARAH WATLING

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the Universitys objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and in certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press 198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America

Sarah Watling 2019

First published in Great Britain by Jonathan Cape

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer

A copy of this books Cataloging-in-Publication Data is on file with the Library of Congress.

ISBN 9780190867416

For Sara Willis And for Julian Walton

Contents

Words are so misleading. Noel Olivier

On 7 September 1962, in a lofty house on Kensington Park Road, a showdown took place between Christopher Hassall and Noel Olivier. Hassall was a hefty, good-looking and multi-talented man; an actor and poet in his youth, he had for many years collaborated with Ivor Novello as his lyricist. Together they had produced some of the most popular musical shows in British theatre of the 1930s and 40s: Glamorous Night, Careless Rapture, The Dancing Years, Kings Rhapsody. In 1953, Hassall had published a well-received biography of his friend, the patron of the arts, Eddie Marsh. Now fifty years old, he was a popular man, comfortable in literary and theatrical circles, a man with a certain air of glamour; used to a friendly welcome. He counted Noels cousin Laurence Olivier, Larry to Hassall, as a friend. In September 1962, Hassall had all but finished work on the first truly authorised biography of a famed war poet whose romantic profile was familiar to every schoolchild in the country. Noel was supposed to complete the picture.

With her siblings, she had been a key character in the story Hassall was trying to recreate in his book. The Olivier sisters, of whom Noel was the youngest, were the beautiful, enigmatic daughters of an important socialist. They had gone through life intriguing and alarming people, fending off besotted admirers and insisting on surprisingly modern lives for themselves; lives that had sometimes tilted unapologetically towards disreputableness. In other words, Noel should have been a gift to a biographer.

But she had proved an elusive quarry. For more than two years, she had ignored and side-stepped Hassall, put him off and, in doing so, put back the publication of the biography, which was by now more than a year behind its schedule. She is still in a state of psychological resistance which she seems unlikely to overcome, an old friend of Noels warned Hassall. I hope that you will not wait indefinitely.

A planned collection of the poets letters had already been hampered by Noels intransigence. Noel had been one of the earliest and most implacable opponents of publication. Not only had she refused to relinquish any of her own letters, she had also asked that no mention what-soever be made of her in the volume, nor any photos featuring her appear.

Hassall complained that the omission of the Olivier correspondence had left the Letters gravely incomplete. This, of course, was Noels intention. What was told in those missives was not only part of the story of the poets life but part of the story of hers and her sisters: lives that had reached far beyond their entanglement with this posthumously famous man. They had had plenty of opportunities to reconsider their position the Oliviers had first been asked for their letters in 1915 but none of the requests or arguments in the intervening years had changed Noels mind nor had she ever felt much need to engage in the various debates that went on about publication, even to explain her own decision.

When, after some of her closest friends interceded, Noel agreed to meet Hassall, her suggested Friday (she offered him a single, two-hour slot) happened to be a particularly inconvenient evening for him. But Noel had laid down her conditions and so Hassall cancelled his appointments, put together an index of references to her in the biography, and asked his sister to host them in her London home.

On 7 September, the accommodating Joan Hassall put out dinner on a table laid with flowers and candles. Noel arrived punctually. Yet from the moment she appeared at the door, Noel was a disappointment to Hassall. Instead of the anticipated opponent, a minute, shrivelled, old woman, with no hat but a mass of very white hair, limped forward, dragging her right leg, he told a friend, everything about her seemed afflicted ; her face, thin and drawn, made her nose seem too big and protruding.

Wrong-footed by this first surprise, Hassall proceeded in confusion. What can I do to help? Noel asked when she arrived and yet how could she not know? She was carrying only a small handbag, which meant she had not brought the letters he was counting on, and claimed not even to know where they were. I havent rummaged, she announced maddeningly. He asked if he could see the letters, if she did find them; she recoiled and then hedged. Perhaps they could at least use the time to go through the index: he offered to read out passages from his book that mentioned Noel, for vetting and even correction, but she declined and instead, after a dinner in which a bewildered Hassall left the conversation to his sister, departed the house with a small black briefcase (provided by Joan), stuffed full of the typescript pages to read at her own leisure. It will be very painful, she said, taking the bag. Not a bit, came the reply. It isnt the least bit boring; you might even be amused by some of it. Hassall walked Noel through the dark to the tube station and watched her limp towards the escalator. He raised his hand to wave. She did not turn.

It was hard to imagine the beguiling teen who had once captivated Hassalls subject, Rupert Brooke. The real Noel, Hassall insisted, was repulsive, a poor little char, who yet smiled sweetly at him, with a soft, kindly look in her eyes; she was a pathetic creature, so ravaged as to rob him of a worthy opponent, who yet managed to frustrate all of his intentions for the meeting, remaining doggedly non-committal and non-compliant in the face of both charm and hectoring, someone who forced him to admit: Ive never met such a difficult customer. Noel, it seemed, had entirely confounded him.

Despite this unpromising start, as he reflected on the evening, Hassall was cautiously optimistic. Perhaps, reading the biography, Noel would be profoundly shocked, acutely embarrassed; perhaps she would recognise that reticence is vain and fully co-operate. Only then did he realise that Noel had managed to get away without leaving her address.

That Noel Olivier should humbly overcome one biographer, and resent the intrusions of various others, begs the question of why someone would dare to write a whole book about her and her sisters. Margery, Brynhild, Daphne and Noel never courted attention (which is not to say they didnt receive it). There is no reason to think they would have approved of such a thing. Charting the struggle between Noel and Christopher Hassall seeing her challenge him over the interpretation of events he had no experience of, and she could have no academic distance from illuminated, for me, the wrangle, the theft and the responsibility of biography.