CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

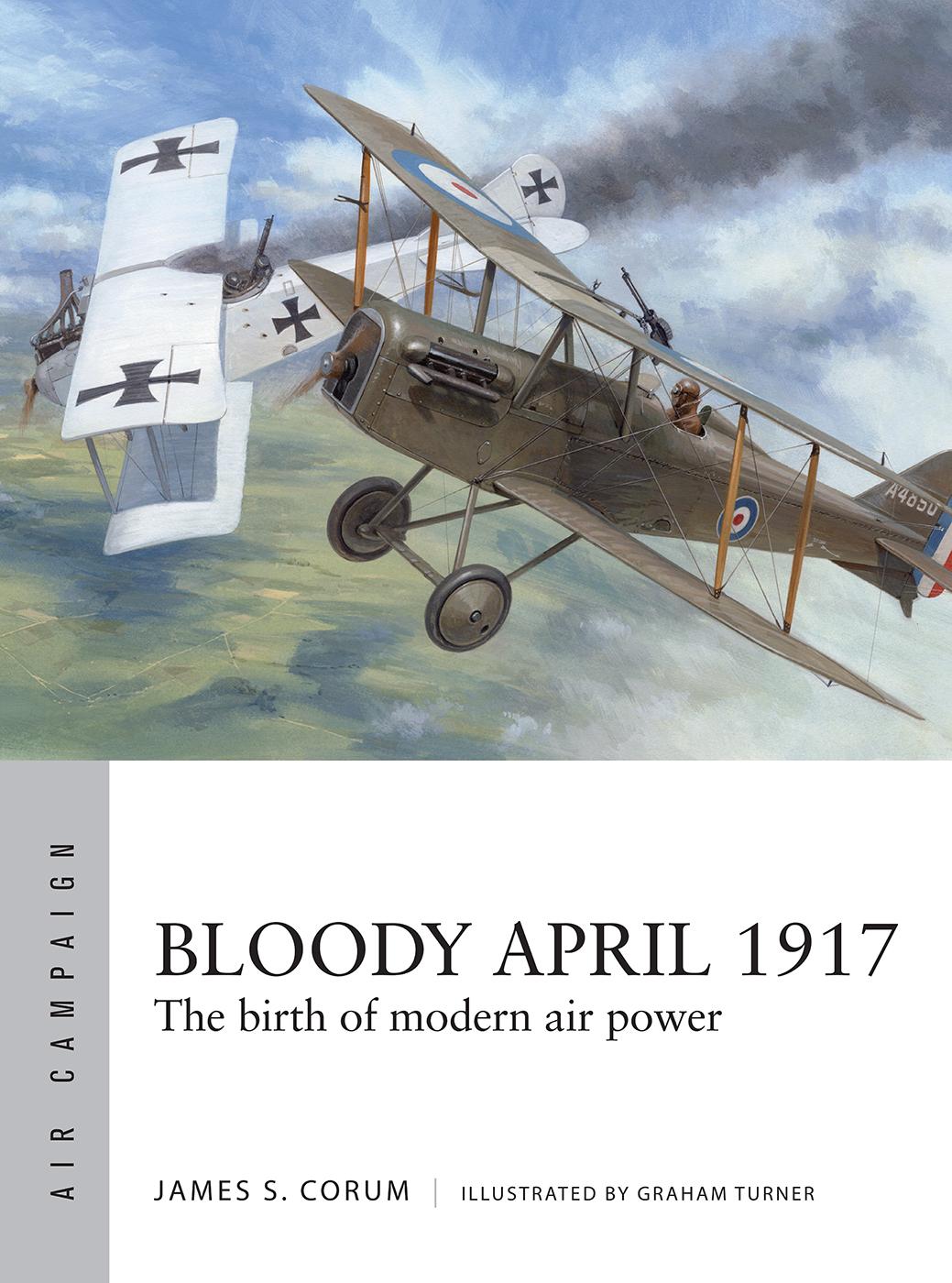

The Allied offensive of April 1917, known as the Nivelle Offensive, brought an entirely new level of operational airpower to the World War I battlefields. The previous year had seen the first true air campaigns at Verdun and the Somme, in which bombers, reconnaissance aircraft and fighters all supported the operational plan. Yet those air campaigns were relatively primitive in operational control, organization and tactics compared to the more complex air campaigns waged in April 1917 by the British in the Arras sector and the French at Chemin des Dames. The Germans also developed new organizations and operational doctrine for their defensive campaign.

Aerial photograph of Western Front trenches. Aerial photography was the primary intelligence-gathering method for all combatant armies. By 1916, thousands of photographs a week were taken and analyzed by the Allied and German Air Services. (IWM Q 105741)

The air campaign of spring 1917 saw significant changes in the use of airpower, to the extent that the period represents a major evolutionary step forward. While most books and articles about the World War I air war focus on the exploits of the fighter aces, it must be noted that fighters were only one factor in the use of operational airpower, and not even the most important. In terms of military strategy and operations, the celebrated aces performed a subordinate role and were not the main mission for air operations. This book will focus on Allied and German airpower at the operational level in spring 1917 it was at this level that fundamental changes in doctrine, tactics and organization were made and how this affected the outcome of the war.

For the Allied and the German senior commanders in 1917, the main role of airpower was to support the ground armies. In particular, this meant that airpowers primary mission was to support the artillery. Without constant aerial reconnaissance, and without the efforts of the radio-equipped artillery observation squadrons of the Allies and the Germans, the primary weapon of World War I armies artillery could not be used effectively. Two-seater reconnaissance and observation aircraft constituted most of the Royal Flying Corps, the German Luftstreitkrfte and the French ServiceAronautique in 1917. The fighter squadrons fought to gain air superiority over the front to allow the reconnaissance and artillery flyers of both sides to conduct their essential missions.

Spring of 1917 prompted major changes for the aviation forces in organization, command and control, and in operational, defensive and offensive air doctrine. The spring 1917 campaign also saw major changes in the equipment and tactics of aviation forces. By early 1917, the three air services were vastly different from the year before. In October 1916, the Germans had reorganized their air service into the Luftstreitkrfte, which was given responsibility and command of all German aviation forces, including balloons, anti-aircraft guns, home and training units as well as front-line units. The Luftstreitkrfte had its own General Staff and commanded all aviation, serving as a modern air force with its own commander and operating, like the army, under the direction of Germanys Supreme High Command (Oberste Heeresleitung).

In 1917, the Luftstreitkrfte organized its front aviation units into groups, squadrons and flights, with most units assigned to one of Germanys 19 armies in the field. Each army had an army aviation commander. Due to this rapid expansion of units in the winter of 191617, the Luftstreitkrfte created the position of Group Commander. The Group Commander, with his staff, commanded reconnaissance, artillery and escort squadrons (called Schutzstaffel) for a sector of the front aligned to support one of the armys corps. The Luftstreitkrfte had created its own signals service to ensure army aviation and group commanders were fully tied to the army units they supported. The French Service Aronautique underwent changes after the Verdun battles. In late 1916, the squadron size was expanded to ten aircraft, and squadrons were now normally organized into combat groups of three or four squadrons, under a group commander. In early 1917, the French also created the position of air commander for each army group, who would oversee the plans and operations of the army aviation commanders. The British Royal Flying Corps was rapidly expanding. RFC wings, a group of three or more squadrons, were organized into air brigades, with command headquarters for two or more wings. A RFC brigade served as the aviation command and control element for each of the British field armies.

Air doctrine early in the war mostly consisted of short memos and directives, but 1917 saw air services publishing extensive manuals at the operational level, specifying how a large number of squadrons and groups would coordinate their efforts to support the campaign plan. The campaign plans of all the armies included extensive and detailed annexes for air operations, detailing which air units would support which ground units and in what manner. The armies and air services assessed the 1916 campaigns and applied the best practices learned on the battlefield.

In spring 1917, the British and French armies aimed to achieve a grand operational breakthrough at the centre of the German Hindenburg Line at two points: the British Army front at Arras to the north; and to the south, the French front at Chemin des Dames. This breakthrough would enable the envelopment of armies in the central part of the German front, leading to the collapse of the German Army on the Western Front. It was a grand plan supported by maximum effort from the RFC and the French Service Aronautique, which committed about 40 per cent of their front aircraft to the operation. RFC and French Air Service aircraft significantly outnumbered those of the Luftstreitkrfte. The Allies also had the advantage in numbers of divisions and artillery pieces, and both the British and French armies would use tanks in the offensive.

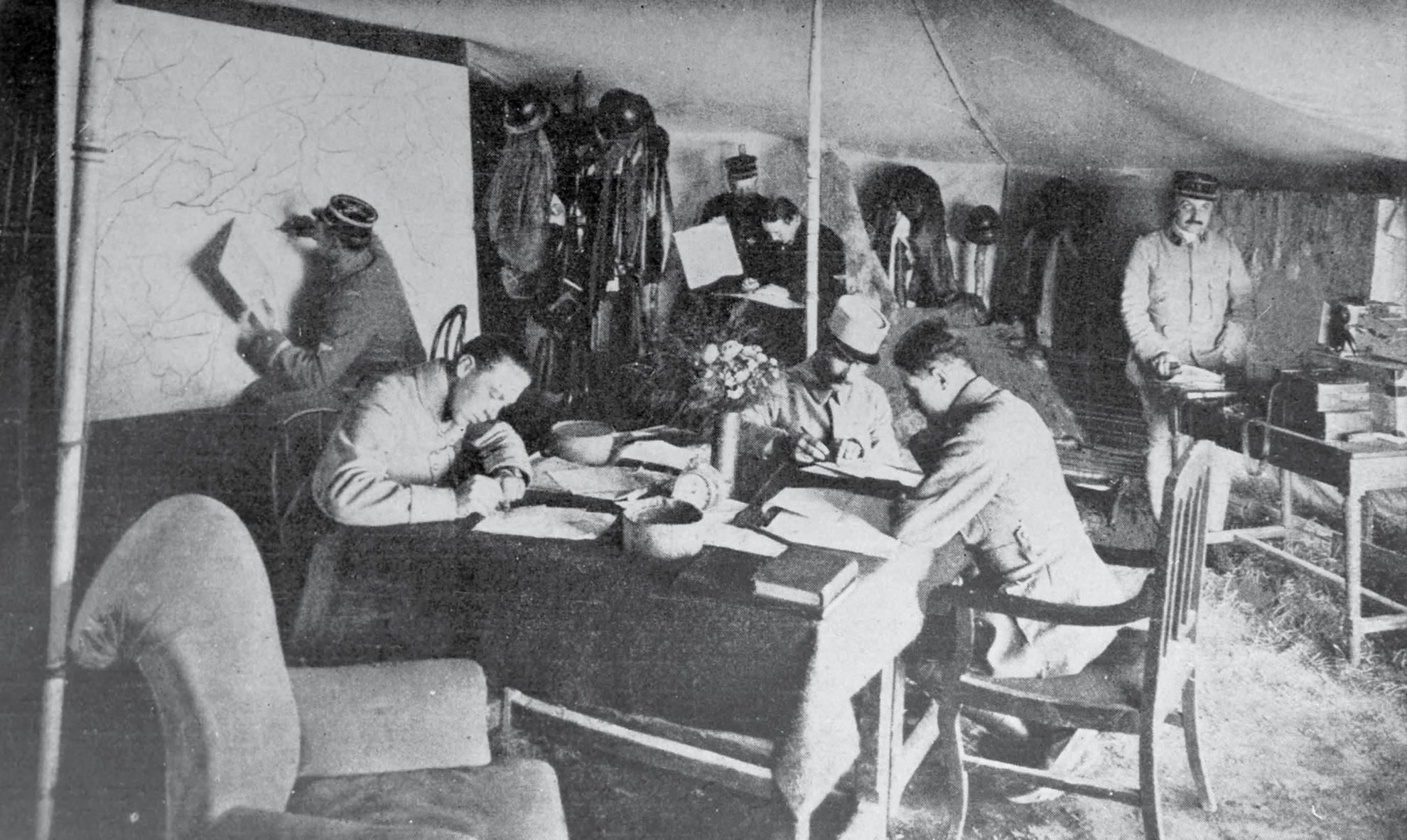

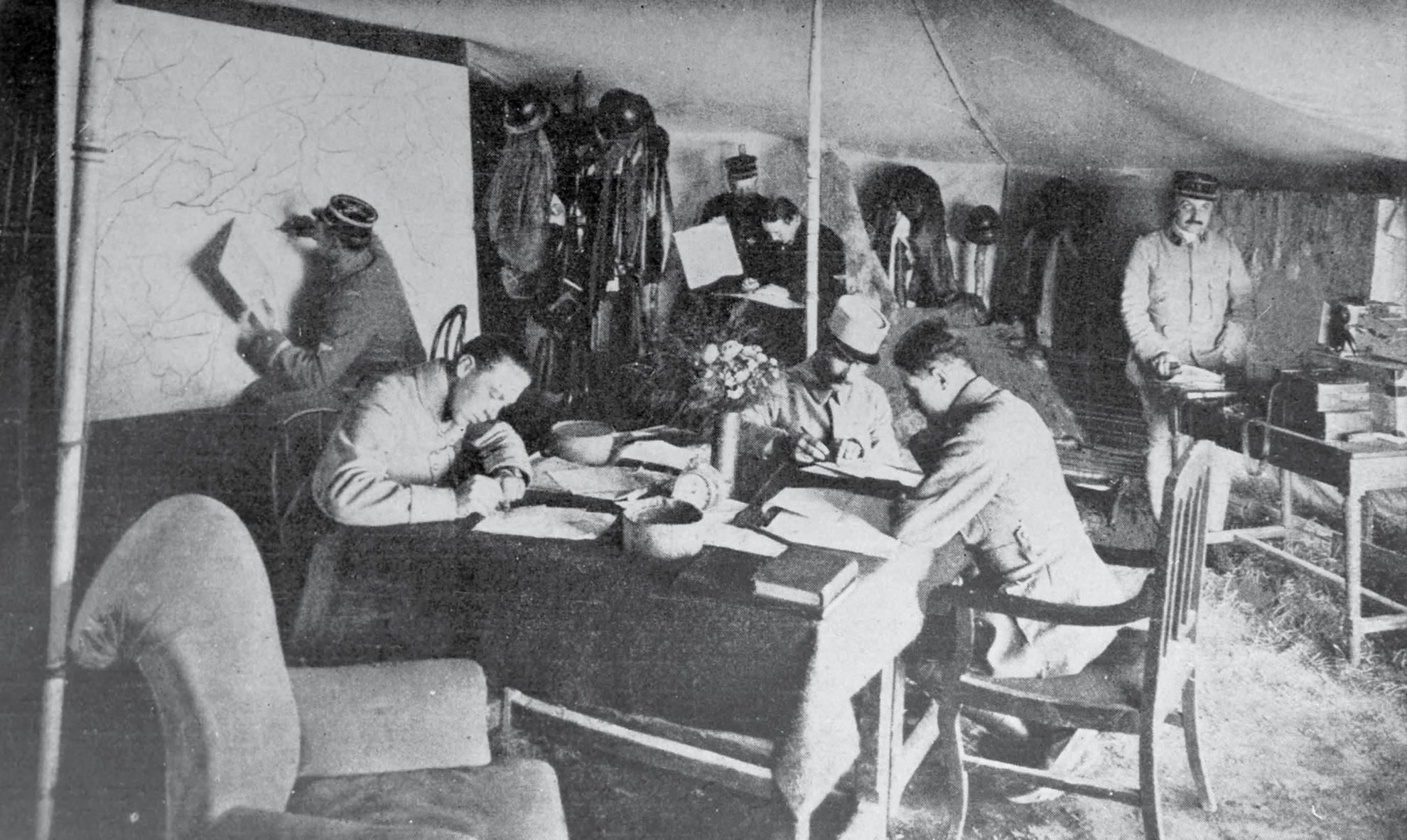

French Air Service intelligence officers in 1917, developing the air operations plans for the Nivelle Offensive. Early in the war, all the air services developed their own general staffs and intelligence sections to oversee planning and operations. (Photo 12/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

Facing this onslaught was a German Army that, although outnumbered, held strong defensive positions. They employed their new doctrine of elastic defence, which relied on the placement of reserves supported by mobile artillery groups close behind threatened points at the front and ready for immediate counter-attack. Their defence was also supported by the Air Service, which had been reinforced, and operated under an effective command and communications system that made it flexible.

The grandiose Nivelle plan failed badly. The one bright spot of the offensive was the British success in overrunning the German stronghold at Vimy Ridge on the morning of 9 April, 1917. It was a brilliantly conducted attack where the RFCs support was key to the success. In contrast, the rest of the Nivelle Offensive resulted in heavy losses for both the British and the French armies for little strategic gain, and is remembered infamously as Bloody April because of the loss of more than 200 aircraft shot down in combat, and the death, wounding or capture of more than 300 RFC aircrew. Aside from a few stellar accomplishments by individual flyers, the campaign was a complete failure from an air perspective.