Introduction

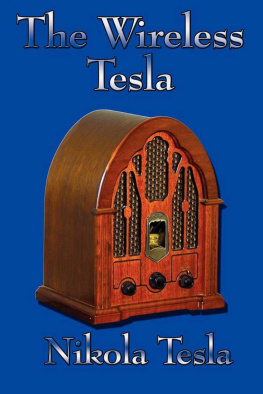

In February 1892, Nikola Tesla (18561943) was in London, about to give the lecture that would make his career. Born to a Serbian family living in a tiny village in Croatia, Tesla had emigrated to America in 1884 to become an inventor. In 1888, he had broken into electrical engineering circles with a new alternating current (AC) motor that used several currents (hence the name polyphase). After his motor patents were purchased by George Westinghouse, Tesla had moved on to experimenting with the electromagnetic waves recently discovered by Heinrich Hertz. Tesla hoped to use the phenomena of these new waves to create a wireless lighting system.

Eager to learn about Teslas preliminary results with Hertzian waves, British men of science had invited Tesla to speak before the Institution of Electrical Engineers. Anticipating a huge turnout, the electrical engineers had decided to hold the lecture not in their usual meeting place (which held 400), but rather the theater of the Royal Institution, which could accommodate 800. In return for this favor, the Royal Institution asked Tesla to repeat his lecture the following night for its members.

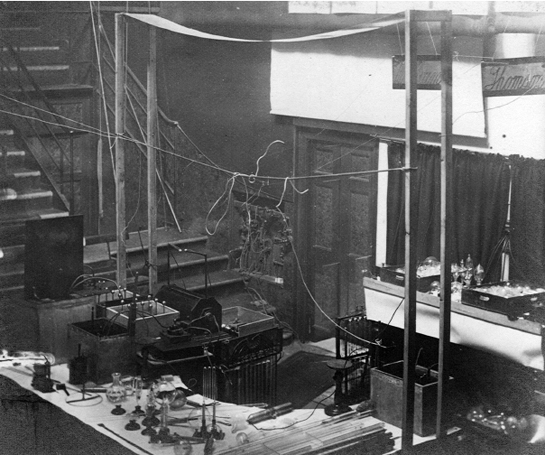

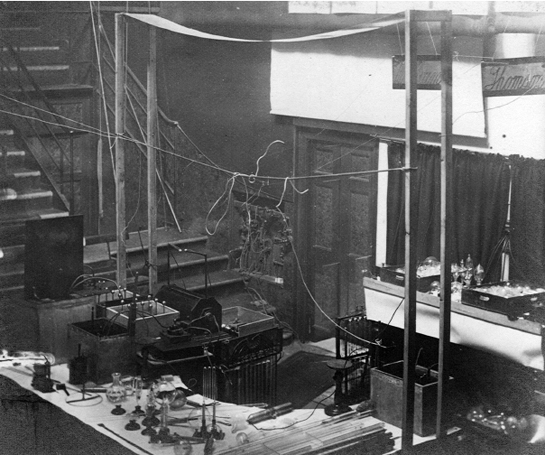

The lecture hall at the Royal Institution, as it was set up for Teslas talk in 1892.

As he strode onto the stage at the Royal Institution, Tesla knew there was a great deal riding on this lecture. For the scientists in the audience, Tesla wanted to establish his credentials in discovery. Not only had he found out new things about electromagnetic waves, but also he wanted to persuade British physicists that they were wrong in assuming that the waves were transverse, as predicted by James Clerk Maxwell. Tesla had instead concluded that Hertzian waves were longitudinal like sound waves.

For the engineers in the crowd, Tesla wanted to make clear his claims to being the sole inventor of the polyphase motor. In the course of developing this motor, he had filed patent applications in Britain and Germany, but he had neither granted licenses to European manufacturers nor sued infringers. Even more troubling was that several individuals, such as Galileo Ferraris in Italy and Michael Dolivo-Dobrowolsky in Germany, were regarded by some as the actual inventors of the polyphase motor. To Tesla, the best way to establish his claims to the AC motor was to use this lecture to show that he was a true genius, obviously superior to his rivals. But how does one show genius?

Teslas answer was a lecture that mixed scientific demonstration and showmanship. He began with several brilliant demonstrations directed towards the leading British engineers and scientists in the front row. Standing on an insulated platform, he brought his body into contact with one terminal of his oscillating transformer and streams of light burst forth from the other terminal. Turning to the audience, Tesla smiled and asked, Can there be a more interesting study than that of alternating currents?

Although the journal Engineering later grumbled that it was a breach of the dramatic canons to start with an experiment of such brilliancy, and then to descend to others of less importance, the audience loved it and broke into applause.his coil to perform more wonders: Six-inch sparks jumped between balls; two long wires, one foot apart and stretched across the well of the theater, were made to glow blue along their entire length; and between two wire circles he created a palpitating purple disk of great beauty. In honor of Lord Kelvin, the prominent British physicist, Tesla used his coil to illuminate a sign that spelled out his common name, William Thomson. [Fig. 9]

As Tesla showed wonder after wonder, reported a commentator in Nature, the interest of [the] audience deepened into enthusiasm. Captivated by his modesty and charm, the audience found that Teslas broken English and imperfect explanations did not detract from his success. His marvelous skill as an experimentalist was evident and unmistakable. For a full two hours, noted the Electrical Engineer:

Mr. Tesla kept his audience spellbound, with easy confidence and the most modest manner possible displaying his experiments, and suggesting, one after another, outlooks for the practical application of his researches.... Even at the end, Mr. Tesla tantalisingly [sic] informed his listeners that he had shown them but one-third of what he was prepared to do, and the whole audience... remained in their seats unwilling to disperse, insisting upon more, and Mr. Tesla had to deliver a supplementary lecture.

Although it was not customary, at the conclusion of the second performance at the Royal Institution, Lord Rayleigh, a prominent British physicist, insisted on giving a vote of thanks to Tesla. Rayleigh

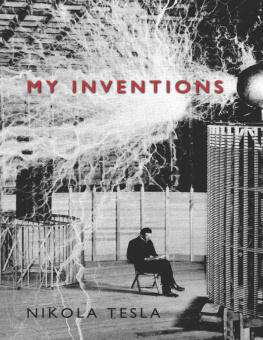

The transmission tower at Teslas Wardenclyffe laboratory.

Tesla was profoundly inspired by Rayleighs compliments. Up to that time, Tesla said, I never realized that I possessed any particular gift of discovery but Lord Rayleigh, whom I always considered as an ideal man of science, had said so. Tesla interpreted Rayleighs praise in a particular way; if he was indeed destined not just to invent but to discover, Tesla felt that henceforth I should concentrate on some big idea.

Over the next decade, the big idea that Tesla pursued was wireless power. Utilizing the Tesla coil he had demonstrated in the London lectures, Tesla moved from lighting a few lamps wirelessly across a room to developing a system to broadcast power around the world. At Colorado Springs in 1899, he built a giant Tesla coil that he thought created low-frequency oscillating currents that traveled through the earths crust. Elated, Tesla returned to New York and using a loan from J. P. Morgan, built an elaborate plant at Wardenclyffe, Long Island, between 1901 and 1905. From this plant, Tesla confidently expected to be able to transmit power, telegrams, and telephone calls anywhere in the world.