To our great and gracious God and for the Jellicoe family

First published in Great Britain in 2005 by

Pen & Sword Military

an imprint of

Pen & Sword Books Ltd

47 Chruch Street

Barnsley

South Yorkshire

S70 2AS

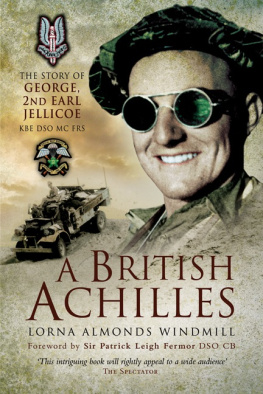

Copyright Lorna Almonds Windmill, 2005

ISBN 1-84415-354-1

eISBN 9781781597255

The right of Lorna Almonds Windmill to be identified as Author of this Work has been asserted by her in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical including photocopying, recording or by any information storage and retrieval system, without permission from the Publisher in writing.

Typeset in 11/13pt Sabon by

Concept, Huddersfield, West Yorkshire

Printed and bound in England by

CPI UK

For a complete list of Pen & Sword titles please contact

PEN & SWORD BOOKS LIMITED

47 Chruch Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS, England

E-mail: enquiries@pen-and-sword.co.uk

Website: www.pen-and-sword.co.uk

Contents

(September 1939 December 1944)

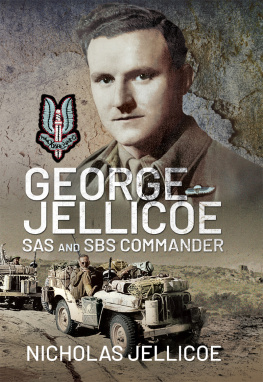

[The Admirals son; the Coldstream Guards; action in the Western Desert; the SAS; the SBS; SAS Raids on Crete, Sardinia, SOE mission to Rhodes, Sea raids and action in the Greek Islands; Bucketforce; the Peloponnese; the Liberation of Patras and Athens; Pompeforce.]

(January 1945 December 2004)

[Washington; Brussels; the Soviet Desk; the Baghdad Pact; Lord-in-Waiting; Minister of Housing; Home Office Minister; First Lord of the Admiralty; Opposition; Member of Cabinet; Resignation; The British Overseas Trade Board; Medical Research Council and Aids; Prevention of Terrorism; The House of Lords Committee on Committees.]

I burn my candle at both ends;

it will not last the night.

But O my foes and ah my friends

it gives a splendid light!

Emily Dickens

Foreword

For children born early in the Great War, as I was, the name of Admiral Sir John Jellicoe and the Battle of Jutland rang in our ears like the echo of a conflict of giants. Children a few years older could remember or said they could the thunder of the guns of our Grand Fleet and the enemys High Seas Fleet rolling inland from the mists of the Dogger Bank. By the time we could take all this in, Jutland had risen through history into myth; the name was murmured in the same breath as Trafalgar and the Armada. We learnt how the great battle had kept the enemy locked in port and out of action for the remaining years of the war and how, when they surrendered at the end of it, the High Seas Fleet of our enemy scuttled itself in the depths of Scapa Flow.

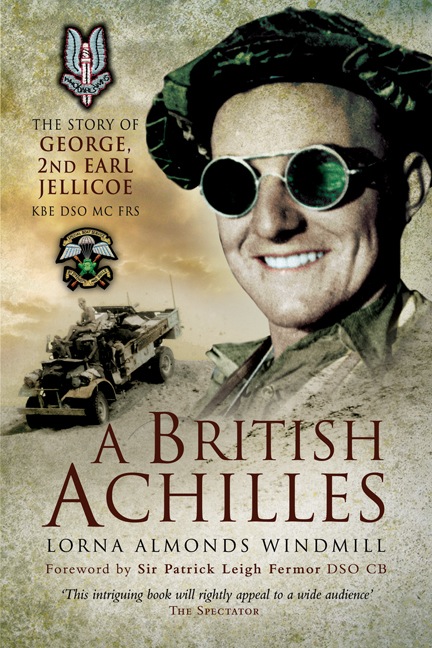

Admiral Jellicoes son is the subject of this book. The second Earl Jellicoe George among friends first loomed in my case during my first infiltration into occupied Crete at a few minutes past midnight on 23 June 1942. Loomed is the right word, for it was pitch dark and he was no more than a shadow in a rubber dinghy heading for the rope-ladder up the side of HMS Porcupine , the ten-ton motorboat which had briefly dropped anchor with its engine ticking over, now almost inaudibly, under a steep southern inlet of Crete. I was heading for the shore in another dinghy, and for a moment we were almost within touching distance. There was just time to exchange names and greetings. Then he boarded and was gone; the only one to make it back from a five-man SAS raid on Heraklion aerodrome, leaving behind them a chaos of burnt-out aircraft and exploded petrol and ammunition dumps scattered over the enemys airfields.

By the time my signaller and I stepped ashore, the vessel had vanished and I didnt actually see this new acquaintance till fifteen months later; the dark upheaval inland swallowed us up for the next fourteen of them. We were the latest addition to a handful of SOE who comprised a military mission to help the Cretan resistance. Some of them were waiting on the beach all armed and we headed up a canyon. It was the start of a strange peripatetic cave-life.

The war was at a critical phase. Rommel and his Afrika Korps were advancing fast across Libya, so fast that, two days earlier, Porcupine , instead of setting off from Bardia, had shifted in haste to Mersa Matruh, 100 miles further east. Except for an occasional submarine, we were now cut off by sea; but somehow tales of the activities of George Jellicoe and his fellow-raiders made their way to our wintry grottos. The deeds of the Long Range Desert Group, the Special Air Service and then the Special Boat Service cheered us up, under the stalactites, and the names of David Stirling, Paddy Blair Mayne, Andy Lassen, David Sutherland and George Jellicoe became household words to us.

Thanks to our meeting in the dark, Georges interested us most. When we met the following year in Cairo and became friends, I caught up with his adventures, and those of his fellow-irregulars, and filled in the gaps or thought I did, until recently I began reading the typescript of Lorna Almonds Windmills excellent biography. (The mass of material and all the changes of scene are powerfully knit in her vigorous and apposite style, and her own military background must have been a great help.) George and I had many friends and many places in common; I only learnt how many as a result of reading this biography.

When he founded and commanded the SBS I was astounded to learn that the base for his flotilla and his buccaneers had been the old Crusader Castle of Athlit, Le Chteau des Plerins, bang on the sea at Haifa, under Mount Carmel. It had been my military billet too, the year before, with a gathering of Cretans listening to my totally ignorant discourses on the German and Italian weapons we hoped to capture one day. Later, I was interested to learn more of the background as to how Jellicoe and Ian Patterson pedalled at full speed into the heart of Athens while the tail of the German army was hastening out at the other end of the city. His name is rightly honoured in Greece, with which he has kept an abiding link. This was notably corroborated after the war by General Christodoulos Tsigantes, the legendary commander of the Greek Hieros Lochos, or Sacred Squadron which, in the last phase of the war, he led victoriously all the way from the Middle East to Rimini. General Tsigantes died in England during the Colonels dictatorship, asking George for the hospitality of his village churchyard in the Wiltshire downs. When the dictatorship fell, his remains were translated to free Greece. His name and dates, and a quotation from Homer, are inscribed in Greek on the headstone above the empty grave. Between them runs the famous epitaph from Thucidides.

General Tsigantes

18981970

When great men die

The whole earth is their sepulchre

Now that he was at last visible, Georges face, with its piercing eyes, the prominent bridge to his nose, his jutting chin and his cheerful laugh, gave him the look of a young Roman centurion of boundless vigour and capacity and, as the post war years advanced, the features, without loss of youth, kept in step, advancing to legate, proconsul, consul and almost imperator. In real life it went even faster; he was a brigadier at twenty-six and adorned with a whole chime of gongs. Just as after demobilization, when he eventually plunged into diplomacy, he soon filled an important post in Washington, at the very moment when diplomats were flitting east in a covey, and later became Deputy Secretary General of the Baghdad Pact. Stepping into politics, he quickly advanced to First Lord of the Admiralty and Conservative Leader of the House of Lords. He has a first-rate brain, passionate application to whatever he takes on, diligence, flair and tireless energy. Thank God, all this is balanced by an equally impetuous verve in the pursuit of the good things in life, the enjoyment of friendship, in skiing and in alertness for random pleasure. We all know how, years ago, this landed him in the soup for something which anywhere else in the world would have been brushed aside. But he was a member of the Government. One fellow minister had got into serious trouble with someone who might have been a danger, and had evaded the truth. Another had erred through clinical pluralism. Rather than bring down more trouble on his side, perhaps subconsciously prompted by the spectre of William of Wykeham, he unnecessarily but honourably and quixotically resigned, stepping forever off the ladder of advancement. The author wonders what heights he might have reached if he had remained in office. So do I.