Table of Contents

TRANSLATORS ACKNOWLEDGEMENT

I am particularly indebted to Professor Zdzisaw Waaszewski for reading and checking the first draft of this translation for accuracy, and for his countless fruitful suggestions and wise comments.

N.C.

LIST OF ILLUSTRATIONS

1. Karol Lanckoroski with his daughter Karolina c.1900. K. Lanckoroska, Energiczna Pedagogia.

2. Lanckoroski family c.1901, Karol with his wife Magorzata and children Antoni and Karolina.

3. Adelajda and Karolina Lanckoroski, c.1910. K.L., Pan Jacek, Tygodnik Powszechny, 1995, No. 3.

4. Magorzata Eleonora ne Lichnowsky, wife of Karol Lanckoroski.

5. Karol Lanckoroski with his son Antoni, c.1915.

6. Palace in Rozd, before 1939. K.L., Rozd , Tygodnik Powszechny , 1995, No. 35.

7. Karolina Lanckoroska in Rozd, 1938. K.L., Rozd, Tygodnik Powszechny, 1995, No. 35.

8. Dr K. Lanckoroska. K.L., Ludzie W. Rozdole, Tygodnik Powszechny , 1995, No. 35.

9. Lanckoroski Palace in Chopy near Komarno, before 1939. K.L., Wspomnienia wojenne.

10. K.L.s concentration camp number in Ravensbrck. K.L., Wspomnienia wojenne, p.246.

11. Carl Burckhardt, President of the International Red Cross, in Geneva, K.L., Wspomnienia wojenne, p.330.

12. In Italy, 1945. K.L., Wspomnienia wojenne, p.335.

13. K.L., Public Relations Officer with Polish 2 Corps in Italy.

14. Officers stars on K.L.s uniform.

15. In Rome, 1946. Polish students/soldiers in Italy 1945-47, compiler Roman Lewicki, London 1996, p. 40.

16. Academic Reunion in Rome, 31 July 1947.

17. Geneva, January 1947. Polish students/soldiers in Italy 1945-1947, compiler Roman Lewicki, London, 1996, p.40.

18. Lieutenant Karolina Lanckoroska, 7 February 1948. Polish students /soldiers in Italy, compiler Roman Lewicki, London, 1996, p.11.

19. Karolina Lanckoroska, lecturer. Polish students/soldiers in Italy, compiler Roman Lewicki, London, 1996, p.76.

20. Karolina Lanckoroska with her brother Antoni in Venice, September 1954.

The Partition of Poland in 1939

NOTE ON PRONUNCIATION

The Polish language is written as it is spoken. Another advantage is that the stress is almost always on the second-last syllable of the word. Ideally, as with any language, one should listen to a native speaker for fine-tuning. But the notes below should help with the pronunciation of the names of people and places in this book. Take a few personal names, starting with the authors:

Karolina Lanckoroska = Karol-EE-na Lants-kor-ONska (i is pronounced ee, c like ts and the Polish sounds like the Spanish in Seor)

Sikorski = Shee-KOR-skee

Choryna = Hor-on-ZHINN-a (Ch is a hard-breathing sound, as in the Scots loch; is a nasal sound, like the French on; sounds like the French je)

Ryszard = RISH-art (sz sounds like the English sh)

Krzeczunowicz = K-zhetchun-O-vitch (rz sounds like the French je; cz like the English ch in church; the frequent combination szcz in Polish is pronounced like the English sound produced in freSH CHoice, and Polish w = English v)

Rkas = RENK-as ( is a nasal sound, like the French in)

Place names:

Warszawa (Warsaw) = Var-SHAV-a (Polish a is always pronounced ah)

Krakw = KRAK-oof (Polish = English oo; w = v, or f at the end of a word)

od = Woodge (Polish = English W; d = dg as in edge)

Lww = Lvoof

Stanisaww = Stanis-WAH-voof

Przemyl = PSHAY-Mishl ( is a soft sh and is a soft ch)

Rozd = ROZ-doow (final sounds like wit without the it)

Wrocaw = VROTS-waff

Koomyja = Kowo-MEE-ya (j is pronounced like the y in yet)

Wodzisaw = Vo-DZHEE-swaff

Brzezie = B-ZHAY-zheeay

Katowice = Kahto-VITS-ay

cki = WANT-skee

PREFACE

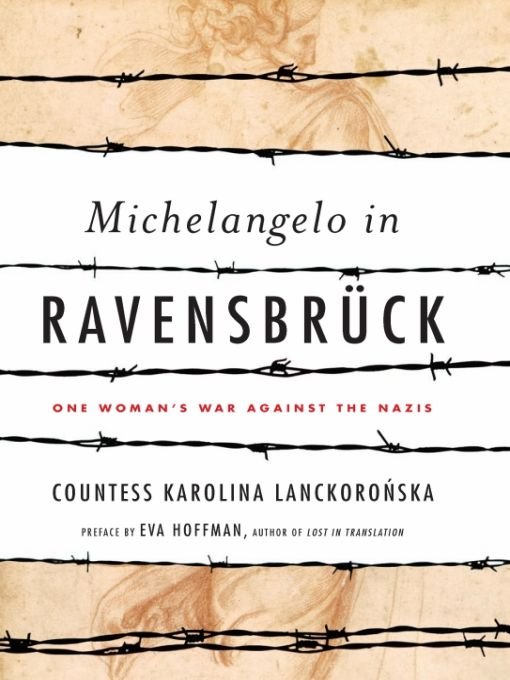

The publication of Karolina Lanckoroskas memoir of struggle and survival in Poland during World War II is an event of great interest. Poland, during the Second World War, was the site of two catastrophes: the Holocaust and the war of occupation and conquest against the country as a whole. While the human dimension of the Holocaust has been made indelibly vivid through a body of powerful personal testimony, the other aspects of the Polish war are known to American readers, at best, as remote history. Lanckoroskas narrative, written mostly during the war years, gives us rare insight into some of that historys complexities, while introducing us to a fascinating story and an extraordinary personality.

Lanckoroskas personality may initially seem distant from us in its social formation and almost stern code of behavior and honor, but it grows both more familiar and more deeply impressive as she moves through her dramatic and unexpected journey. Countess Lanckoroska was an aristocrat with a cosmopolitan background and strong proclivities for the scholarly life. Through the vicissitudes of Polish history, her ancestors settled in Austria at the end of the eighteenth century. During her formative years, her family was involved in the highest echelons of Austrian life, while keeping the Polish side of their identity intact. The young Countess Lanckoroska seemed to choose Poland as her homeland out of an affinity for that countrys people, culture, and sensibility.

The outbreak of the war found Lanckoroska in Lvov, where she held the post of professor in Renaissance Italian artthe first woman in Poland to achieve this rank in her field.

Her decision to become engaged in the resistance movement, which arose in opposition to the Soviet and Nazi invasions, seemed to follow unhesitantingly from her convictions and affiliations. Her descriptions of working in the underground, with its dangers and its ethos of solidarity, make for some of the most fascinating sections of the book. Her activities in Soviet-occupied Lvov were mostly humanitarian, but her network of contacts was wide. As the danger of discovery became apparent, she had to flee, ironically enough, into the Nazi-occupied Polish territories where she walked a dangerous line between legal and illegal activities, organizing relief efforts for prisoners of the Nazi regime throughout occupied Poland. Her native German helped her in dealing with Nazi officials, whom she confronted with shrewd perceptiveness and uncompromising honesty. In one case, this exasperating combination led one of her Nazi interlocutors, Hans Kruger, to confess toor boast ofthe murder of twenty-three professors from the University of Lvov. (Lanckoroska later tried to make the knowledge of this terrible war-crime public, but was ignored by the German authorities). During the war, she was to some extent protected by her highly placed international connections, but eventually her refusal to disavow her loyalty to Poland led to her imprisonment in Nazi jails and incarceration in the concentration camp of Ravensbrck.