Preparing to thank the enormous number of people who helped to make Tara Revisited possible is a daunting task. It is one of the great rewards of doing research for a book like this that so many people open their archives and photo collections, their files and memory banks to share so generously. The kindness of those whose names follow made my undertaking over the past decade much easier, more pleasant, as well as more challenging. Im afraid of committing sins of omission, but at the same time, I want to acknowledge so many who contributed, especially the kindnesses extended by the staffs of the United Daughters of the Confederacy in Richmond, the Southern Historical Collection at the University of North Carolina (Chapel Hill), the South Carolina Historical Society in Charleston, the United States Military History Institute in Carlisle, Pennsylvania, the Natchez Trace Collection at the University of Texas, Austin, the Caroliniana Library at the University of South Carolina, Columbia, the Mississippi State Archives, Jackson, the Virginia Historical Society, Richmond, the Virginia State Library, Richmond, the Historic New Orleans Collection, the Woodruff Library at Emory University, the National Archives, and most especially, the Library of Congress, with special thanks to Mary Ison. Invitations from both Clemson University and the College of Charleston over the years have been welcome excuses to visit valued colleagues, drop into archives, and enjoy Carolina hospitality which lives up to its legendary reputation. I owe an enormous debt as well to Randolph-Macon Womans College in Lynchburg, Virginia, which hosted me on research forays; I encourage others to visit their splendid Collection of the Writings of Virginia Women. Frances White Webb, who called my attention to this treasure trove, Ruth Anne Edwards, and Nancy Gray were all instrumental in making my visits such enjoyable research excursions.

Special mention must be made of those who were so generous with assistance as I was seeking illustrations and other material for my book over the years: Lawrence Strichman, Diane B. Jacobs, Arthur Barrett, John A. Martin, Jr., Dick Schrader, Harriet McDougal, David Moltke-Hansen, Charles Reagan Wilson, Anne Marie Price, Mark Wetherington, Devon Goddard, Guy Swanson, Diana Arecco, Jim Heisler, Jamila Jefferson, Jo Anne Kendall, Randy Sparks, Kathy Haldane, Leah Arroyo, Joan Cashin, Ken Greenberg, Carol Bleser, Jean Baker, Susanna Delfino, Lee Ann Whites, Bennett Singer, Nicoletta Karam, Michael Melcher, Pilar Olivo, Lisa Cardyn, and, most especially, Corrine Hudgins of the Museum of the Confederacy.

Many at Abbeville Press deserve appreciation and praise. First and foremost, I salute Mark Magowan, whose vision shaped the book from the outset and whose championing of the project has been invaluable. I remain much indebted to the editorial skills of Constance Herndon, whose talents measurably improved the manuscript. Celia Fullers indelible influence is evident from cover to cover; she was a terrific designer for this project, particularly attuned to the books (and my own) demanding requirements. I also want to thank Walton Rawls, Laura Straus, and Owen Dugan, with special gratitude for Mary Christians numerous and critical contributions at the final stages of the project.

The many hosts who have fed and sheltered me while completing my work are legendary: Jane Gottlieb and David Obst, Christine Heyrman and Tom Carter, Barbara and Paul Uhlmann, Jr., Clara and Richard Crockatt, Cora and Winthrop Jordan, Paul and Bobbie Simms, Jeffrey and Deborah Tatro, Constance Schultz, Fran and Emory Thomas, Marie Tyler-McGraw, Patricia Montgomery, Gene Roe, Pilar Viladas, and most especially, Nicholas G. Harris. Finally, I can never hope to repay a couple who has been rolling out the red carpet for me in D.C. for over two decades: Craig and Fran DOoge, along with their daughters, Charlotte and Justine.

My mother, Claudene Clinton, has been a generous fan over the last six books, and I hope she will continue her boundless enthusiasm for the next half-dozen as well. My father-in-law, Edwin Colbert, cheerfully parted with his facsimile copies of Harpers Weekly for the Civil War years, a loan that was much appreciated. My husband, Daniel Colbert, and our two sons, Drew and Ned, were not so cheerful to part with me, as was frequently required for the sake of this project. During 1992 alone, I made twelve research trips, on top of my weekly commute to Cambridge for teaching, making theirs an extraordinary sacrifice, for which I remain, as always, in their debt.

Catherine Clinton

Before Fort Sumters

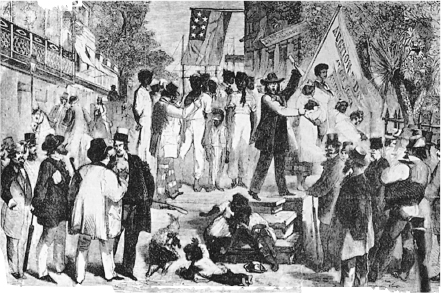

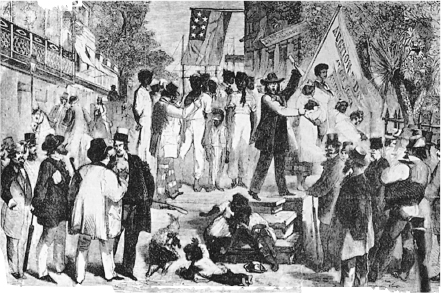

In this portrait of workers in the cotton field, black women carry loads on their heads in traditional African fashion.

In the antebellum South there were indeed belles and beaux and lavish entertainments. But there were also harsh epidemics, scorching heat, and hardscrabble living on the border. A complex interdependency developed between myth and reality, upcountry and low country, coastal and interior, urban and rural. Lush, conspicuous splendor was meant to hide the wrenching work necessary to maintain the grandiose estates that sprawled westward along with settlement. Slave owners hoped their pristine homes could in some way obscure the relentless filth and grind to which their human chattel were subjected in the building of the cotton kingdom. Most white Southerners participated in this conspiracy, and all but a few knew that their role as co-conspirators was to conjure up a dream worldfor Europeans only. It was a white mans fantasy, one that required bravado and delusion for full enjoyment.

With the early settlements of Americas southern frontier through the middle of the seventeenth century, English promoters shamelessly hawked the South as a paradise on eartha claim flatly contradicted by the realities of the first encounters. Sir Richard Grenville had led an expedition in 1584 that landed off the Carolina coast at Roanoke Island, and when he departed he left fifteen men behind to hold the fort. But when John White returned with a group of settlers in 1587, they found no survivors. White then sailed back to England, leaving behind his own small band, which included his granddaughter, Virginia Dare, the first English child born in North America. But the Spanish Armada and other impediments delayed Whites return to Roanoke, and when he landed in August 1590 the settlement had disappeared. This early groups sad fate, which has become a staple of Southern folklore, did not bode well.

And so propagandists went into high gear, with a literary outpouring that was nothing short of a crusade to convince Europeans that America was a glorious opportunity rather than a dangerous exile. British merchant Edward Bland wrote The Discovery of New Britain in 1651, advising readers to settle in the territory from thirty-five to thirty-seven degrees north latitudewell aware that Sir Walter Raleighs Morrow of History located Eden along the thirty-fifth parallel north. Heaven, he claimed, could be found along a line that ran from Fayetteville, North Carolina, to Memphis, Tennessee (where Elvis Presley built his own paradise, Graceland).

An earlier generation of European explorers had criss-crossed the southern reaches of the continent in search of fountains of youth and cities of gold, but by the seventeenth century Europeans sought other treasures. They hoped to cultivate silkworms, grapes, orchards of olives, dates, lemons, and other exotic treesin short, to turn America into a veritable Garden of Eden.

Next page