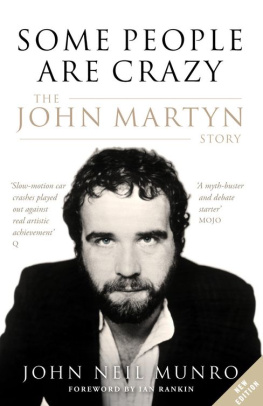

SOLID AIR

THE LIFE OF JOHN MARTYN

By

Chris Nickson

SOLID AIR: THE LIFE OF JOHN MARTYN

First published in 2011

By Creative Content Ltd, Roxburghe House, Roxburghe House, 273-287 Regent Street, London, W1B 2HA.

Copyright 2011 Creative Content Ltd

The moral right of Chris Nickson to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act, 1988.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced or transmitted in any form by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopying, recording or any information storage and retrieval system, without prior permission in writing from the publisher nor be otherwise circulated in any form or binding or cover other than that in which it is published.

In view of the possibility of human error by the authors, editors or publishers of the material contained herein, neither Creative Content Ltd. nor any other party involved in the preparation of this material warrants that the information contained herein is in every respect accurate or complete and they are not responsible for any errors or omissions, or for the results obtained from the use of such material.

The views expressed in this publication are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the opinion or policy of Creative Content Ltd. or any employing organization unless specifically stated

Typesetting by CPI Rowe

Cover Design by Michael Page and Daniel at HCT Design

Cover Photograph Suzanna Cramtom

ISBN 978-1-906790-26-4

INTRODUCTION

At the beginning of October 2003, websites run by John Martyn fans were giddy with the rumour that John was set to play a pair of shows at a pub close to his home in rural Ireland in November.

The big man was back and to those who loved his music it seemed like a miracle.

In April 2003, John Martyns right leg had been amputated below the knee. It was an item that didnt make the music press, although plenty of friends and well-wishers, including Eric Clapton, heard the news and sent their good wishes to him in hospital. In time, he was fitted with a prosthetic limb and discharged from hospital.

One man, one operation, carried out successfully. It wasnt the end of the world; millions around the globe had survived similar things and continued with their lives. And there was no doubt that John was a survivor; the pendulum swings of his career over almost four decades had proved that.

But this was different. John was in his mid-50s and to come back, especially from something as traumatic as this, took a wealth of energy and spirit, things that could have been in short supply.

The gigs that marked his return took place on November 7 and 8 at Connollys of Leap, a tiny bar out in West Cork, known for the music it staged, with acts like Roy Harper and Hothouse Flowers passing through its doors. It was hardly a high-profile venue, but there was enough pressure on John without any visibility. The BBC were filming the first night for part of a documentary on John. He hadnt played live in two years and even though John was a veteran performer, with longtime keyboard player Spencer Cozens and bassist John Giblin backing him up, there were nerves.

For several months hed been undergoing physical therapy, getting used to his prosthetic leg but he chose to perform from a wheelchair. It offered safety. This was a test for him, a full performance of 14 songs, ranging from favourites like Solid Air and May You Never to newer work and a selection of covers, like Portisheads Glory Box, and Suzanne, wrapping up with the old standard Goodnight Irene.

Fans travelled not only from all around Ireland, but from across the globe for the shows, to show their support for John and to welcome him back. His nerves vanished once he began playing. After all, this was what he did, the way he defined himself to the world, through his songs and his music. Doing this was vital.

John told me he had to get back to playing, said an old friend, singer-songwriter Bridget St. John, whod visited him at his Kilkenny home during the summer and who spoke to him after the Connollys shows, its the only thing that makes him feel great. And he was satisfied with the results, she noted, saying I know his gigs went great.

It was the kind of confidence boost he desperately needed after all that had happened. Thered been trauma, physical and mental, and he needed to re-establish exactly who he was.

Whatever hes doing is in balance, St. John observed. I think as long as he has his thing in balance, its fine for him.

Obviously, it worked. He was certain enough of his abilities to book a 15-date UK tour in April and May, 2004. That would come around the same time as the BBC were airing their documentary in March, with his name fresh in peoples minds.

In many ways, it was set to be a longer test run to see just how viable continuing as a performer might be. The schedule wasnt easy, but still better and less gruelling than many John had undertaken in the past. There were no long distances to travel between dates and hed be surrounded by his band, musicians he knew well and trusted, and who were used to him and his foibles.

There was also the small matter of a new album. His last release has been Glasgow Walker, all the way back in 1999. Since then, any John Martyn material that had appeared on record shop shelves had been repackaged, or old gigs spruced up for CD release. Welcome fare, some of it, but there was nothing fresh.

However, before his leg problems had become really bad, Johns band had laid down fresh tracks, working from his material. By now they were old, of course, but they could form the basis of an album. And while John was at home, undergoing rehabilitation, hed recorded his guitar and vocals. Initially it seemed that it wouldnt happen in time for the tour, but maybe after, once he was used to working again. Hed undergone a lot and had plenty to say. But in April 2004, just as the first dates were getting underway, the brand new On the Cobbles hit the shops.

The idea of John away from music was unthinkable. It had been his life since he was 16 and first playing folk clubs in Scotland, under the wing of the late Hamish Imlach. Hed dedicated himself; hed had drive and ambition. Hed started out playing folk music, but quickly accelerated past that barrier, adding electricity, touches of jazz, avant-garde, and whatever he wanted to create his own sound.

While John the musician forged ahead, John the man could be a little more problematic. He loved his drink, and while he could be charming, there was also a temper that lurked not too far below the surface. He was volatile, which could result in knock-down, drag out fights and a few instances of burning personal bridges and sabotaging his career, setting him back several paces on the path.

But at 55, and settled with his partner Teresa, who seemed a good match for him, perhaps all that was finally behind him. Living in the peaceful environment of Kilkenny, away from the razor bustle of the music industry, hed maybe come to terms with and was at peace with himself.

Hed enjoyed a number of revivals since his critical heyday in the 70s, when a gushing Martin Carthy actually kissed his television on seeing John appear on The Old Grey Whistle Test, declaring, Its so good to see our John again! (an apocryphal story, but Carthy admitted its truth). At the end of the 70s he worked with Phil Collins and put out a pair of commercially successful discs. He revisited his old songs in the early 90s, finally finding some small slice of acclaim in the US, and he won plaudits for The Church with One Bell, his 1998 album of covers. The chillout movement hailed him as a godfather, and hed recorded a version of the Beloveds Deliver Me with Sister Bliss from Faithless.