Contents

Guide

Pagebreaks of the print version

Published by

Princeton Architectural Press

70 West 36th Street

New York, NY 10018

www.papress.com

2022 Donald Lee Dahler Jr.

All rights reserved.

ISBN 978-1-64896-035-2 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-64896-131-1 (epub)

No part of this book may be used or reproduced in any manner without written permission from the publisher, except in the context of reviews.

Every reasonable attempt has been made to identify owners of copyright.

Errors or omissions will be corrected in subsequent editions.

Designer: Paul Wagner

Library of Congress Control Number: 2021953031

For Harriet. At long last.

I ride on the gale at my ease

The earth and the heaven between.

Francis Medhurst, The Aeroplane, 1910

CONTENTS

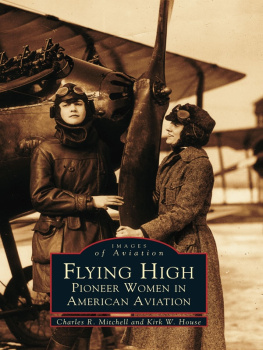

Harriet with a Moisant monoplane in 1911.

PROLOGUE:

If you are afraid, you shall never succeed

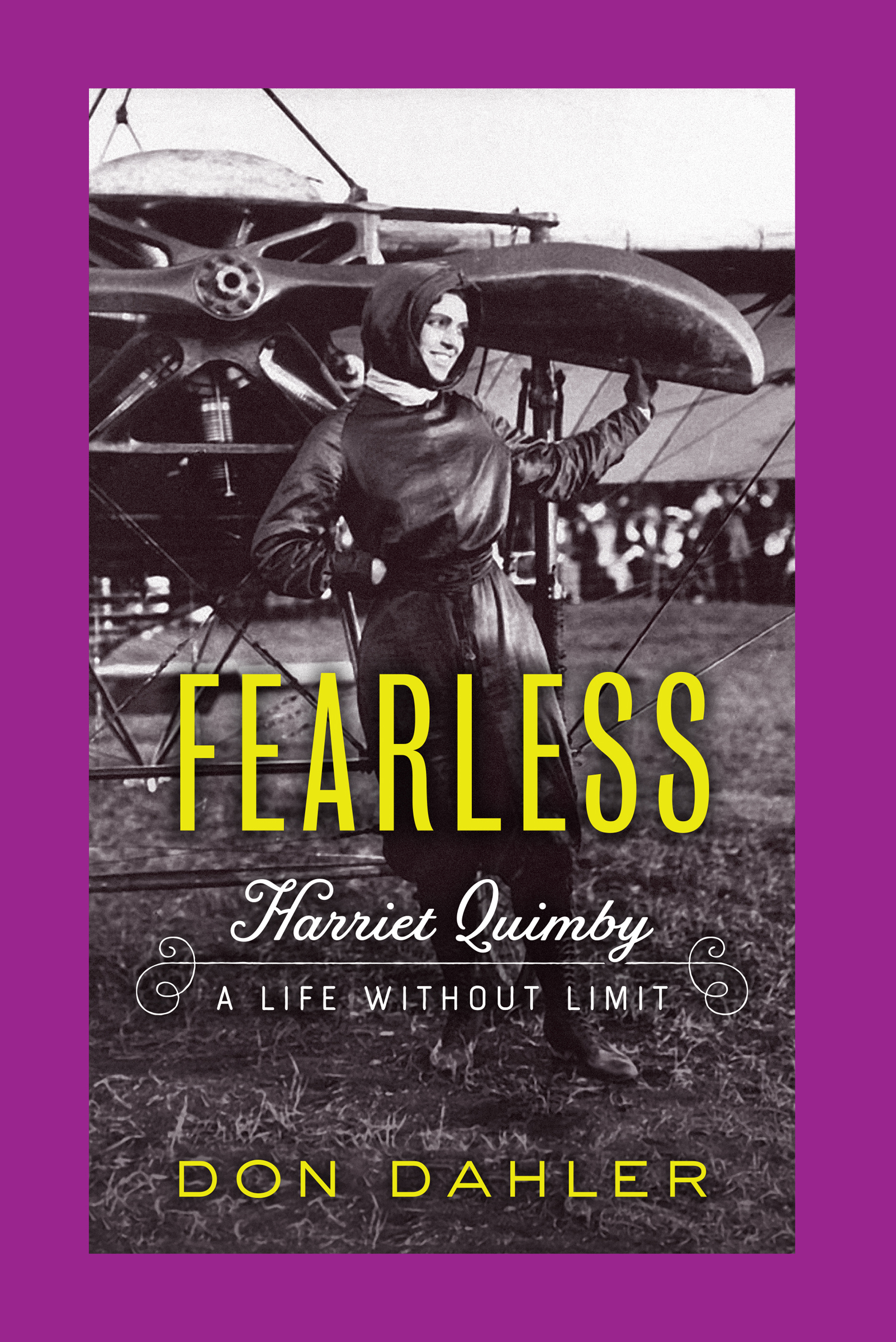

THE SEA BECAME SKY. Wraiths of heavy salt air floated across the White Cliffs of Dover, bestowing their wet caresses on everyone and everything that waited day after day for a break in the fog and lashing rain. But their petrichor marked a subtle change of fortune; there was something stirring in the damp perfume. Of those peering anxiously into the seamless gray wall was a tall, slim, remarkably beautiful woman with jet-black hair and blue-green eyes. Already an established drama columnist, travel writer, and reporter; already a woman who audaciously rode in a race car at over one hundred miles an hour; already a journalist whose investigations led to a public officials resignation, Harriet Quimby was about to take a literal, and literary, leap into the void. If she survived, and there was certainly no guarantee of that, her leap was to be a first for women, and another risk-laden challenge that some of those closest to her begged her to reconsider. Not even a heartbreaking betrayal would sap her determination.

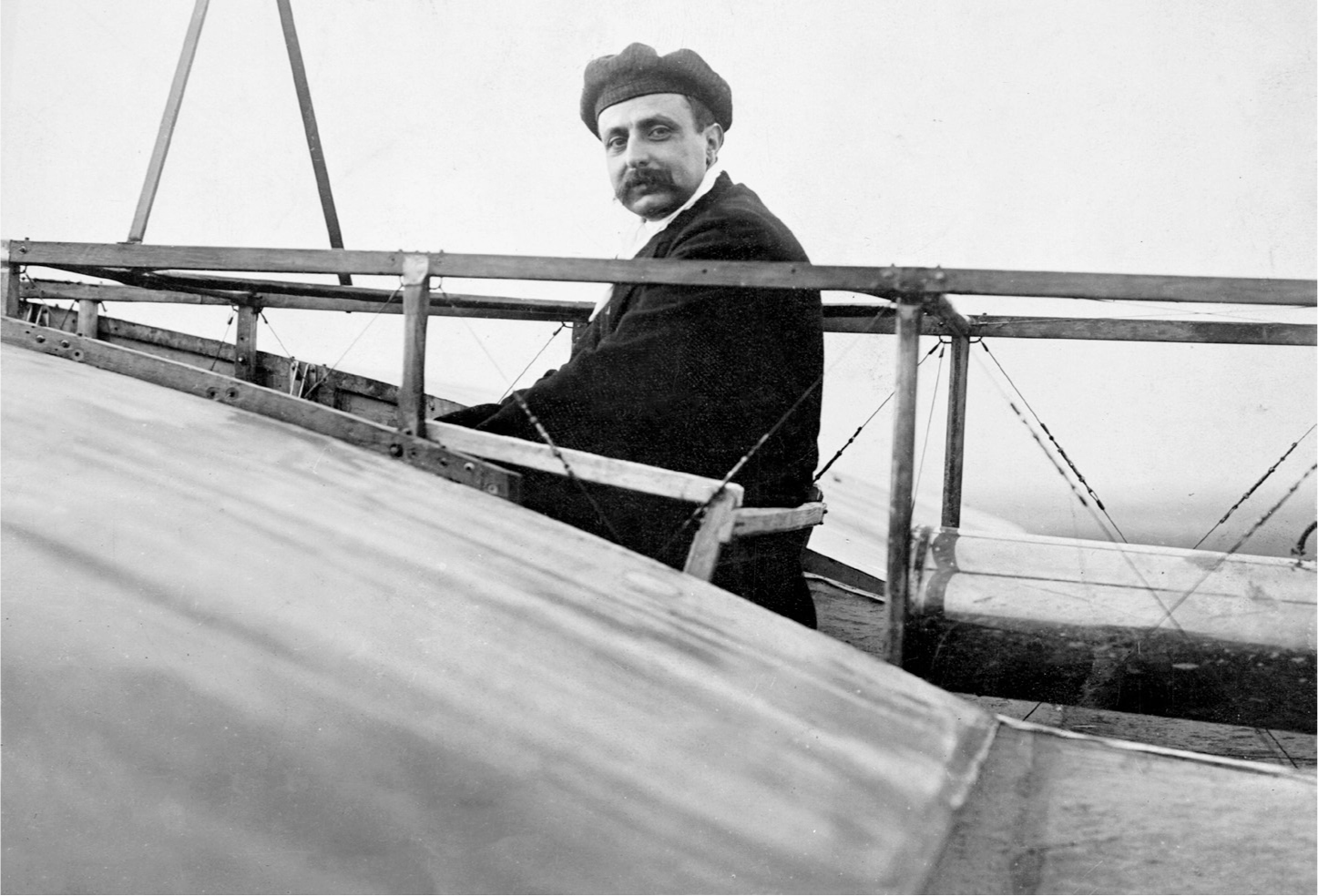

Behind her, a monoplanes bicycle wheels rested delicately on the grass. Borrowed just days earlier from its inventor, Louis Blriot, because the more powerful version she ordered was yet to be completed, it sported a spindly frame made out of ash, fabric-covered wings that spanned twenty-three feet, and a 50-horsepower Gnme rotary engine. An early observer of the racket that little motor made described it this way: Take a motor bicycle, a rolling mill, and a buzz saw, and blend them, and you get something like it. The airplane was held together by a web of wires that made it look more like a marionette than something sturdy enough to cross twenty-two miles of the English Channel.

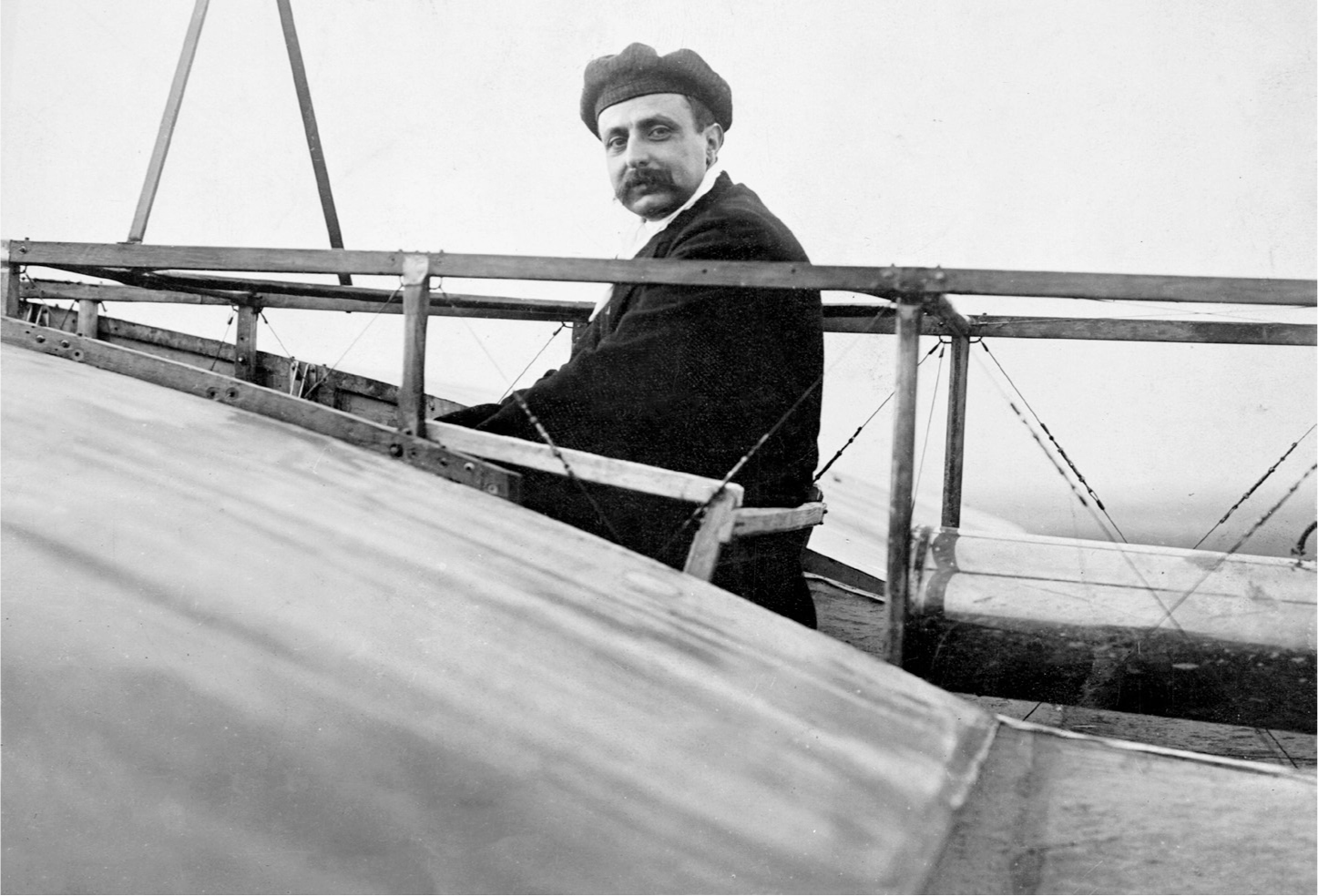

Louis Blriot, inventor of the monoplane and the first to fly across the English Channel.

In 1912, aviation wasnt in its infancy; it was embryonic. Not yet a decade had passed since the brothers Wright trundled and hopscotched their 12-horsepower biplane for all of fifty-seven seconds over the blowing sands of Kitty Hawk beach and into the publics imaginationCaelum certe patet, the sky at least stands open. A spark that smoldered since the days of Daedalus and ancient Greece was ignited, and within just a few years, scores of young men were attending flight schools in the United States and Europe and plunking down thousands of dollars to buy rickety wood-and-linen airplanes, some of which were of questionable design and safety. The year before, a hundred pilots plunged to their deaths. Flight was a Faustian gamble between an early, often gruesome end and enormous fame, as successful aviators were the rock stars of their day, fted by the press and followed by huge crowds of avid fans. Attendance at air shows numbered in the tens of thousands, some eventually swelling to upward of half a million. Fliers could earn thousands of dollars for less than a half-hour in the air. Imagine todays spectacles of the Super Bowl, professional wrestling, NASCAR racing, and gory octagon matches of mixed martial arts, and one gets some sense of the passion, fan loyalty, and, indeed, blood lust driving the early days of aviation. But with one addition: the Grim Reaper stalked almost every air show, often claiming at least one soul. Theres another good man gone, pilot Arch Hoxsey mused on New Years Eve, 1910, after hearing of the violent death of a prominent flyer at a New Orleans event. He would perish himself moments later as he lost control while trying to best his own altitude record.

The first air show on American soil took place at Dominguez Field near Los Angeles not quite a year earlier. What was primarily a moneymaking endeavor for its promoters became the genesis of how Americans saw themselves and their future, reflected in the heroic images of brave aviators soaring and banking and pushing their machines to the edge of existence. It certainly made an indelible impression on one young woman in particular, whose interest in aviation would only continue to grow.

In ten days at Dominguez Field, men set records and became aviation legends. One of those was named Glenn Curtiss, who urged his biplane to the never-before achieved airspeed of fifty-five miles an hour. Glenn was emblematic of the anything-is-possible ethos of turn-of-the-century America. The dapper New York State youthwho sported suits, ties, and on occasion a neatly trimmed Van Dyke beardleft school after the eighth grade to provide for his fatherless family. Looking for adventure on the rutted dirt roads of the small Finger Lakes village of Hammondsport, he first made a name for himself as a bicycle racer and motorcycle designer. He fashioned a working carburetor out of a tomato soup can for his earliest attempt at building one.

By 1907, Glenn could claim the title of fastest man in the world with a run of 136 miles an hour on his own two-wheeled creation. That record established him as one of the leading motor builders in the nation. It was an achievement not ignored by the nascent aviation industry, such as it was. In June of that year, he flew over his hometown in a dirigible made by Thomas Baldwin and powered by his own engine. (The Wright brothers tersely, maybe enviously, rejected Glenns engine design for their own use.) That marked his very first trip aloft. As soon as he landed, and true to his nature, the speed freak whom the press nicknamed Hell Rider set about figuring out how to make the dirigible even faster.

Glenn Curtiss, pioneer aviator and the man dubbed Hell Rider. Photo taken shortly before he won the inaugural Gordon Bennett Trophy in 1909.

After Alexander Graham Bell himself came calling on Glenn to help create a heavier-than-air flying machine, the twenty-nine-year-olds name would forever be linked to humanitys quest to fly. Gone was his obsession with going fast over the ground; Glenn Curtiss wanted to conquer the sky.