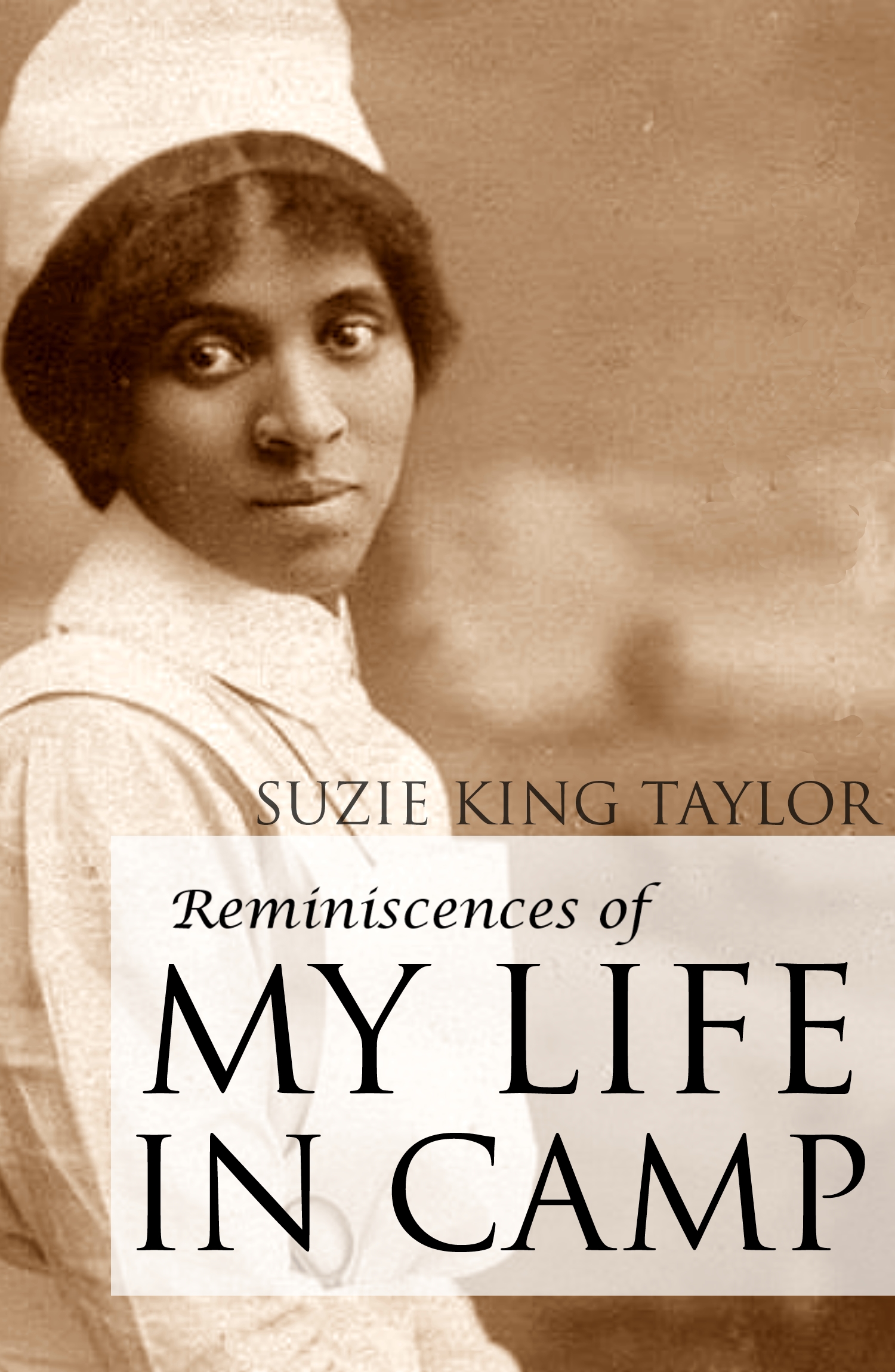

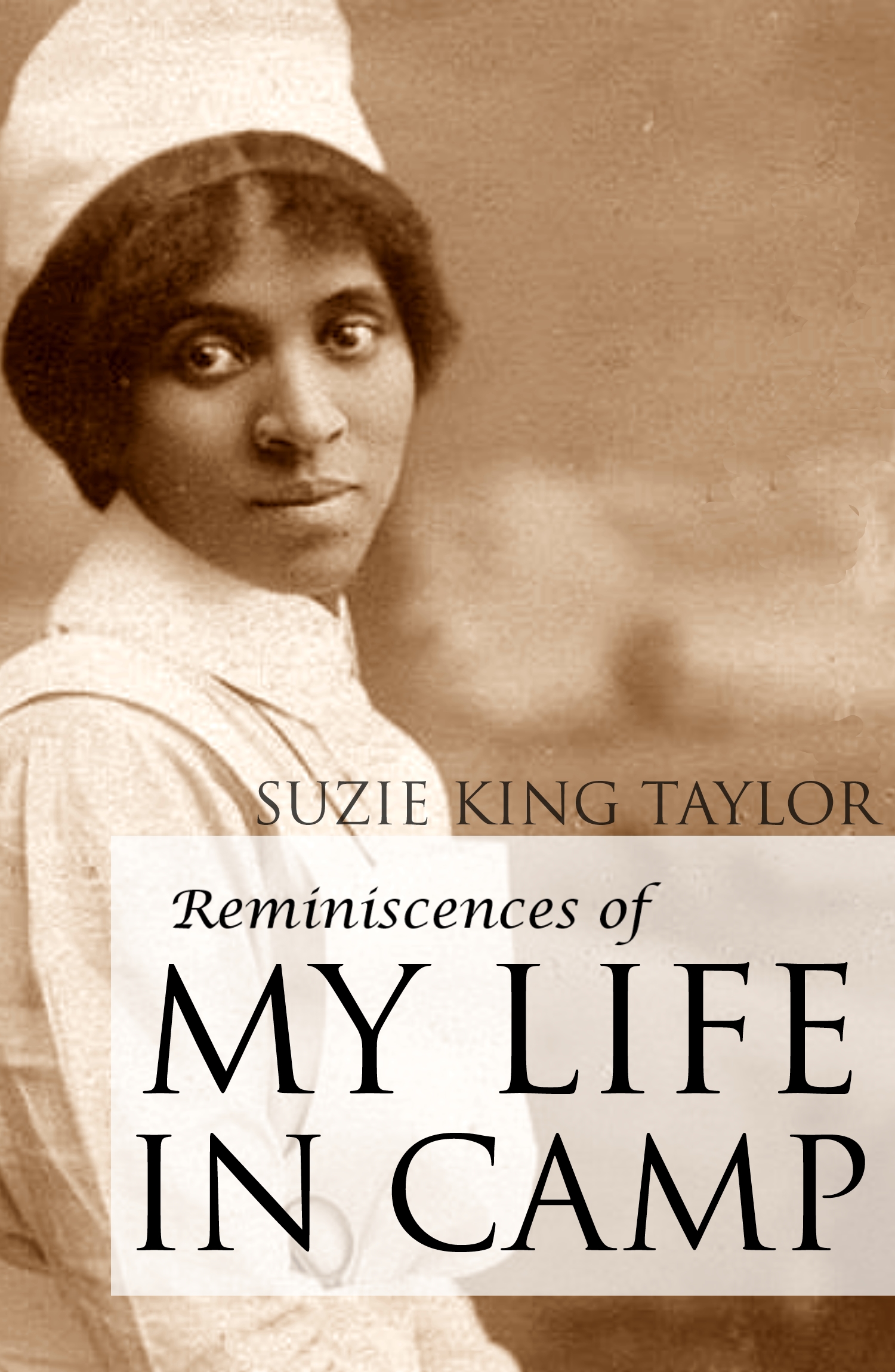

REMINISCENCES OF

MY LIFE IN CAMP

By SUSIE KING TAYLOR

1902

COPYRIGHT 2013 BIG BYTE BOOKS

DISCOVER MORE LOST HISTORY AT BIGBYTEBOOKS.COM

PUBLISHERS NOTES

It would be easy to dismiss Susie King Taylors narrative as a simple recitation of events of camp life in the first black regiment in American History. It is much more than that and should be read for its subtleties throughout and for its not-so-subtle last chapter. The book is not really about camp life but about her experience of having served the Union cause and her dedication to the soldiers who fought.

She does not, in fact, go very deeply into most of the events that characterized her time with the Army. We know next to nothing of her two husbands, little about her son, and almost nothing about her friends. But she does make us aware that hundreds of black women (and nearly 200,000 black men), at enormous risk to their lives and freedom, aided the Union cause.

The reader must pay attention to the cues that signal Ms. Taylors depth of feeling about what she saw and experienced. Sometimes its explicit but more often, its beneath the narrative.

Writing is a difficult endeavor for any professional, no matter how long theyve practiced the craft. Suzie King Taylor had little education before the war and that was accomplished illegally. That she strove to improve herself under the most difficult of circumstances throughout her life is evidenced in her writing and in her time as a teacher to children and adults. This book is an important piece of American autobiography.

A white boat captain she met during the flight from Savannah at the beginning of the war was amazed that a southern black could read and write. In conversation with her, he remarked You seem to be so different from the other colored people who come from the same place you did. I have little doubt that others found Suzie exceptional as well. (The commanders of her regiment thought very highly of her.) There is something of Suzie that comes through her writing and draws you to her, which is remarkable given how little she reveals in personal details.

Often the explicit parts of her story are very short. She remarks in wonder, for example, at how she was able to become acclimated to the horror of seeing and caring for shattered bodies, torn flesh, and dying men.

Her delight at learning to field-strip, clean, and fire a musket well shows how widely her talents expanded during the war. She also relates her clever way of keeping warm in her tent on winter nights without creating a glow that would attract a scolding from the watchman.

Only thirteen when the war began, she was married before it was over. Her husband died in 1866, leaving her pregnant and alone at 18. At the time of writing this book, she was 54 and was still participating in veteran affairs. She makes the almost universal, despairing complaint about the younger generation and their lack of understanding of how much the men and women of her generation had sacrificed to make life better for the future.

She had also come to see what Reconstruction had wrought both North and South. She felt that 1902 Boston was a place where blacks could expect to be treated fairly and well. But she knew of the lynchings and other depredations still carried on in the South. The early years of the 20th century were some of the worst in history for African Americans. Some rights given them after the war were being legislated out of existence. According to the Tuskegee Institute, 3,446 African Americans were murdered in extra-judicial lynchings in the U.S. between 1880 and 1951.

On a trip to Louisiana to see her son, Suzie experienced firsthand how Blacks were treated in the South. The final chapter in this short book is an impassioned, well-voiced appeal for equal rights.

This is also the story of white Americans in the Union Army who were capable of rising enough above institutionalized racial prejudice to recognize the manhood and womanhood in the African Americans with whom they served. The parting missive from Lt. Colonel Trowbridge to his troops, included in this volume, was one of the most eloquent statements of that recognition to come so shortly after the cessation of hostilities.

It is marred by just one sentence:

The nation guarantees to you full protection and justice, and will require from you in return that respect for the laws and orderly deportment which will prove to everyone your right to all the privileges of freemen.

Even today, many Americans forget that the spirit of the Constitution of the United States claimed endowment to all men and women the privileges of freedom; it did not require them to behave in a way that would earn it for them. White Americans of Suzies time could behave badly with no thought of worry about their status as citizens. And sadly, the Colonels hopes for the prospects of his troopers would be delayed for another century.

Taylor wrote one of the loveliest volumes on the Civil War period. Though short and not a detailed account of adventures and battles, it contributes greatly to our understanding of one womans experience during this tumultuous time in our history. Suzie King Taylor died in October of 1912, at the age of 64. She is buried in Massachusetts next to her first husband, Edward King.

To

COLONEL T. W. HIGGINSON

THESE PAGES

ARE GRATEFULLY DEDICATED

PREFACE

I HAVE been asked many times by my friends, and also by members of the Grand Army of the Republic and Womens Relief Corps, to write a book of my army life, during the war of 1861-65, with the regiment of the 1st South Carolina Colored Troops, later called 33d United States Colored Infantry.

At first I did not think I would, but as the years rolled on and my friends were still urging me to start with it, I wrote to Colonel C.T. Trowbridge (who had command of this regiment), asking his opinion and advice on the matter. His answer to me was, Go ahead! write it; that is just what I should do, were I in your place, and I will give you all the assistance you may need, whenever you require it. This inspired me very much.

In 1900 I received a letter from a gentleman, sent from the Executive Mansion at St. Paul, Minn., saying Colonel Trowbridge had told him I was about to write a book, and when it was published he wanted one of the first copies. This, coming from a total stranger, gave me more confidence, so I now present these reminiscences to you, hoping they may prove of some interest, and show how much service and good we can do to each other, and what sacrifices we can make for our liberty and rights, and that there were loyal women, as well as men, in those days, who did not fear shell or shot, who cared for the sick and dying; women who camped and fared as the boys did, and who are still caring for the comrades in their declining years.

So, with the hope that the following pages will accomplish some good and instruction for its readers, I shall proceed with my narrative.

SUSIE KING TAYLOR.

BOSTON, 1902.

***

INTRODUCTION

Thomas Wentworth Higginson was a soldier, abolitionist, author, traveler, and suffragist. His memoir is titled Cheerful Yesterdays .

ACTUAL military life is rarely described by a woman, and this is especially true of a woman whose place was in the ranks, as the wife of a soldier and herself a regimental laundress. No such description has ever been given, I am sure, by one thus connected with a colored regiment; so that the nearly 200,000 black soldiers (178,975) of our Civil War have never before been delineated from the womans point of view. All this gives peculiar interest to this little volume, relating wholly to the career of the very earliest of these regiments, the one described by myself, from a wholly different point of view, in my volume Army Life in a Black Regiment, long since translated into French by the Comtesse de Gasparin under the title Vie Militaire dans un Regiment Noir .

Next page