Copyright 2012 by Geoffrey C. Ward

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data Ward, Geoffrey C.

A disposition to be rich : how a small-town pastors son ruined an American president, brought on a Wall Street crash, and made himself the best-hated man in the United States / by Geoffrey C. Ward.1st ed.

p. cm.

This is a Borzoi bookT.p. verso.

eISBN: 978-0-307-95944-7

1. Ward, Ferdinand De Wilton, 18511925. 2. Capitalists and financiersUnited StatesBiography. 3. Swindlers and swindlingUnited StatesBiography. 4. Financial crisesUnited StatesHistory19th century. 5. Ponzi schemesNew York (State)New YorkHistory19th century. 6. Grant, Ulysses S. (Ulysses Simpson), 18221885Friends and associates. 7. Children of clergyNew York (State)Biography. 8. Ward, F. De W. (Ferdinand De Wilton), 18121891. 9. Rochester (N.Y.)Biography. 10. New York (N.Y.)Biography. I. Title.

CT275.W2752W37 2012

974.703092dc23

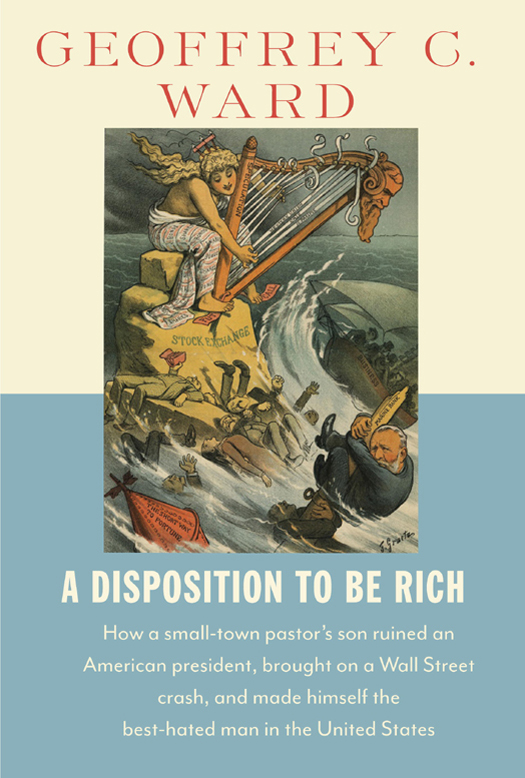

A cartoonist for Puck assessed the chaos Ferdinand Ward had caused on Wall Street eight days after his fraudulent brokerage collapsed; in the foreground, Wards ruined partner, General Ulysses S. Grant, clings to a spar from the Marine National Bank, the financial institution that went down with the firm.

For my grandfather, Clarence Ward,

my father, F. Champion Wardand

for my brother, Andrew, who might have

made a better story out of this material

but was kind enough not to try

Family is what counts.

Everything else is a side-show.

F. C HAMPION W ARD

If you cannot get rid of the family skeleton,

you may as well make it dance.

G EORGE B ERNARD S HAW

CONTENTS

PART ONE

THE PURITAN

PART TWO

ONE OF THE WORST BOYS

PART THREE

THE YOUNG NAPOLEON OF FINANCE

PART FOUR

THE BEST-HATED MAN IN THE UNITED STATES

PART FIVE

THE LOVING FATHER

Prologue

O n the afternoon of August 8, 1885, the streets of Manhattan were given over to grief. Ulysses S. Grant had died five days earlier, after an agonizing fourteen-month struggle, first against financial ruin and then against throat cancer whose every hideous detail had been reported in the newspapers. Nearly a quarter of a million people had shuffled past the ex-presidents bier at City Hall. Now, his coffin was to be borne north along Broadway to a specially prepared vault in Riverside Park at 122nd Street. No eventnot even the funeral procession of Abraham Lincoln along the same street a little more than twenty years earlierhad drawn such crowds to the city. The two-year-old Brooklyn Bridge was closed to vehicles that morning so that Brooklynites could pour across the East River to join their fellow mourners in Manhattan. Passengers occupied each seat and stood in every aisle aboard the trains arriving at Grand Central and Pennsylvania stations; so many extra cars had been added to accommodate them that most trains had to be hauled by two locomotives. Ferries from New Jersey and Staten Island were packed, too, and the new elevated railway brought in some 600,000 more people from the citys outer regions.

One onlooker wrote that the entire length of Broadwayshops, offices, hotels, theaters, apartment buildingswas one sweep of black, and even the tenement dwellers crowded along the side streets hung their windows with tiny flags and strips of inky ribbon. The vast black and silver hearse was drawn by twenty-four black-draped horses, each accompanied by a black groom dressed in black, and it was followed

Somewhere in that living mass stood a slender, alarmingly pale man wearing smoked glasses so that no one would recognize him. The disguise was probably a good idea. Until his arrest the previous spring, Ferdinand Ward had been Grants business partner and apparently so skilled that older financiers had hailed him as the Young Napoleon of Finance. But now, many held him directly responsible for the late generals impoverishmentand even, indirectly, for his death. As Ward himself later wrote, with the strange blend of pride and self-pity he always displayed when alluding to his crimes, he had made himself by the age of thirty-three the best-hated man in the United States. He had no right to be on the street that day, in fact; he had bribed his way out of the Ludlow Street Jail, where he was awaiting the trial for grand larceny that would soon send him to Sing Sing. In this, as in nearly everything else in his long life, he seems simply to have assumed that rules made for others need never apply to him.

Ferdinand Ward was my great-grandfather. I cant remember when I first began to hear stories about him. Nor can I remember who first mentioned him to me. It may have been my late father, who had met his grandfather just once while still a small child, and who remembered him only dimly, as an apparently amiable, impossibly thin old man with a drooping white moustache, rocking on the front porch of a frame house on Staten Island. To a landlocked Ohio boy like my father, the ferry ride across New York Harbor from the Battery had been more memorable than the aged stranger.

Perhaps it was my grandfather, Clarence Ward, who first spoke of his father to me. Though he was brought up by maternal relatives and had spent little time in Ferdinands company, Clarences bright blue eyes, even in his eighties, still mirrored fear and pain at the mention of his fathers name. Little wonder: Ferdinand had hired a man to kidnap my grandfather when he was just ten years old, flooded him with blackmailing letters as a young man, threatened to see to it that he lost his first job, and, finally, took him to courtall to get his hands on the small legacy left to his son by his own late wife.

In any case, by the time I was twelve or thirteen, I knew at least the outlines of Ferdinands story: pious parents, a Presbyterian minister and his wife, both former missionaries to India; an apparently tranquil boyhood in the lovely village of Geneseo, New York; a move to New York at twenty-one, followed by marriage to a wealthy young woman from Brooklyn Heights, and a swift rise on Wall Street that culminated in the 1880 formation of the firm of Grant & Ward, to include both the former president of the United States and James D. Fish, the president of a large Wall Street financial institution, the Marine National Bank. Four years of flush times followed: summer homes, blooded horses, purebred dogs, jewels from Tiffany, European artworks, lavish generosity to family and friends, the birth of a son.

Then, disaster: the collapse of first the Marine Bank, then the firm of Grant & Ward, and panic on Wall Streetall of it blamed on Ferdinand Ward. There was Wards arrest and that of James Fish, and later two sensational trials that demonstrated that both men had deliberately set out to defraud investors, followed by seven years in prison during which Ferdinands wife and both his parents died. Released in 1892, he devoted most of the thirty-three years left to him to harassing the son he barely knew while continuing to hatch schemes by which one person or another was to provide him with money on which to live, funds to which he always seems to have assumed he was somehow entitled. He never changed, never apologized, never explained.