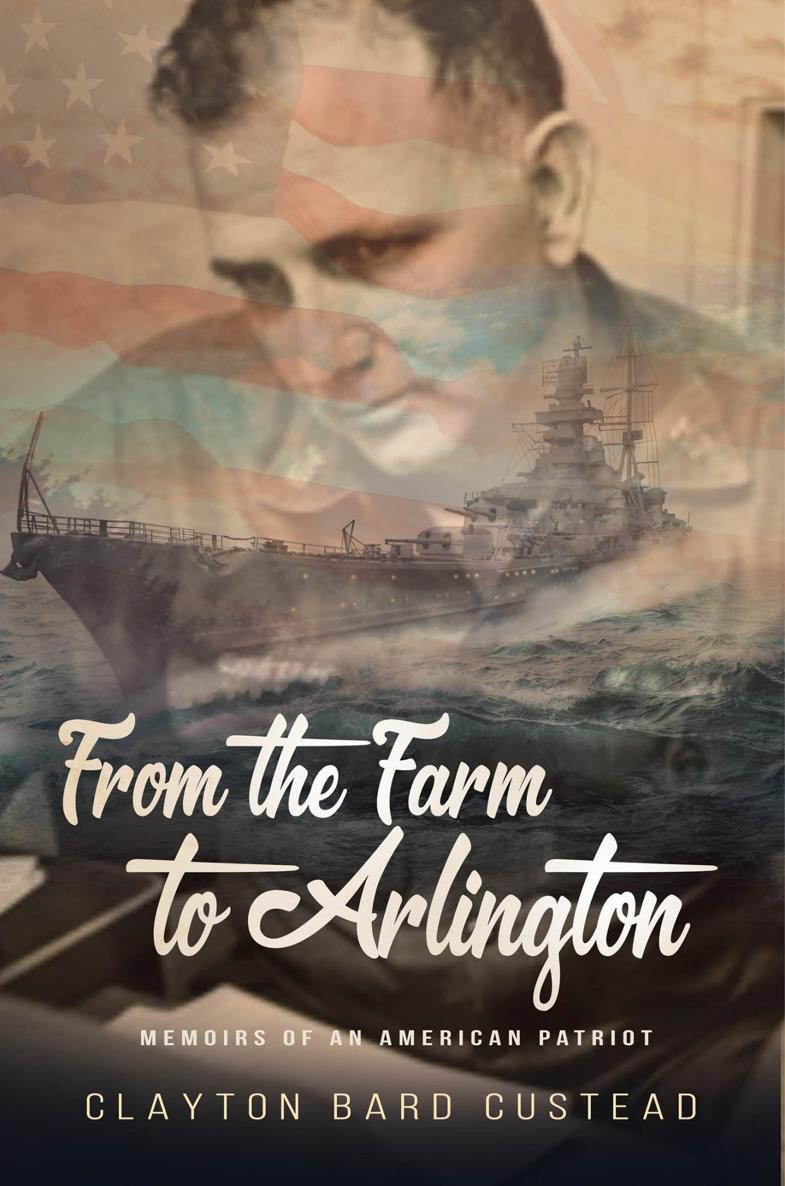

From the Farm to Arlington:

Memoirs of an American Patriot

by Clayton Bard Custead

Copyright 2019 Clayton Bard Custead

ISBN 978-1-63393-877-9

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any meanselectronic, mechanical, photocopy, recording, or any otherexcept for brief quotations in printed reviews, without the prior written permission of the author.

REVIEW COPY: This is an advanced printing subject to corrections and revisions.

Published by

210 60th Street

Virginia Beach, VA 23451

8004354811

www.koehlerbooks.com

INTRODUCTION

THE GENESIS OF THIS BOOK was our fathers stroke. All our lives, he regaled us seven children with tales from his childhood spent on a farm in the Deep South and his twenty-eight-year career serving in the United States Navy. At times, his stories seemed almost too fantastic to be true. The repetitiveness of every single detail of these stories over many years, however, gave weight to their veracity. We often encouraged him to write down these tales, usually after hearing either the same anecdote again or a new one for the first time. We knew his stories were unique and should be captured in writing, if for no other reason than to preserve an important part of our family history. He told us often how he desired to record his memoirs, but he never seemed to know how to get started. Sitting next to his bed in the emergency room the night of his stroke, I realized we had finally run out of time. I knew his speech and writing ability were now permanently impaired and decided that night to help him record his lifes stories.

As a man, my father can best be summarized as a martineta rigid, military disciplinarian who demands complete obedience. I was in the seventh grade at Kensington Junior High School in Maryland when I first came across this strange, French-sounding word on a spelling quiz. This word, martinet, struck me from the first time I encountered it and it has stayed with me through my entire life as it allowed me, for the first time, to understand my father. It was the very essence, the very embodiment of my father, a man who saw lifes choices only in terms of right or wrong. The world to him was either black or white; there existed no grey area. He was a man who imparted upon his five sons and two daughters the now seemingly outdated concepts of chivalry and honor. To my father, there was nothing more contemptible than a man who did not dutifully devote 100 percent of his attention and love to his wife, children, and country.

Growing up, I was terrified of my father, and at times, I mistakenly thought I hated him, especially as I became a young man and naturally started to yearn for independence. His unyielding discipline never ceased, nor did my absolute fear of him. When he addressed me, I concentrated my attention on the tips of my toes. Doing so allowed me to maintain a neutral expression and avoid eye contact. My father viewed direct eye contact by one of his children as a sign of disrespect indicating a need for immediate correction. A neutral expression was a guard against him detecting any attitude, which would prompt him to ask, Do you want me to wipe that smirk off your face? The most nerve-wracking moments occurred when my father commanded me to look him in the eyes despite the unstated but understood rules against this behavior. He only did this while saying something like Do you understand? Look at me and tell me you understand. I dared not follow his commands while every fiber of my being told me that to look him directly in the eyes might shorten my life span.

At slightly over six feet, two inches tall, my father had remarkably long, ape-like arms. I remember that none of us were ever out of his reach. At the dinner table, if any of us said something my father disapproved of or otherwise misbehaved, he would reach out with a humiliating flick of his finger aimed at the side of our heads. The offense may have been something as innocuous as asking Mom to bring the salt shaker in from the kitchen (we learned early that our parents did not wait on us, but that it was our duty to wait on them) or complaining about the food being served. A flick might also punish poor manners, such as taking the last of some food without first inquiring if anyone else would like it. That flick carried a big punch, not due to the physical pain, but because of the accompanying humiliation. It was always followed by a few moments of everyone looking down at their dinner plates in silence until normalcy would naturally return.

I often overheard my father brag to other parents that only a few of his children had ever dared have a temper tantrum, and if it did happen, it had only happened once. He responded to the resultant puzzled looks by explaining. If any of his children had a tantrum, no matter where, even in the checkout line at the grocery store, his response was so swift, violent, and out of proportion that not only the child but his sibling witnesses never considered echoing the offense. My father seldom raised his voice or ever repeated himself. On the few occasions he did, you knew all hell was about to break loose. During the rare times our family went out to dinner, strangers would often go out of their way to stop by our table to complement our parents on what incredibly well-behaved children they had. I am not saying we were perfect, but you might have mistaken us for The Sound of Music s Von Trapp family, only without the lederhosen.

Growing up, I showed signs I was a little out of the ordinary because of the way I was raised, even for the 1960s. For my father, growing up on a farm meant he could work beyond an average mans point of collapse. He possessed an incredible work ethic, born of a mental toughness, which allowed him to ignore pain, hunger, and fatigue until the job was done. He passed this indefatigable work ethic down to his seven children. Seeing his children idle or at play seemed to irritate him to no end. My childhood recollections include washing woodwork or windows every weekend. Each day after school and each evening after dinner, we all had chores such as vacuuming, washing the dishes, or cleaning the kitchen floor. People who came by our house could not believe how clean it always was, especially for having nine people living in it. There was never even a pair of shoes by the back door.

Being raised on a farm means learning to be self-sufficient. My father certainly was, and this was another wonderful trait he handed down to his children, especially his boys. There were only two things my father paid a professional to do: mount and balance tires and align the steering. This was only because he did not own the expensive equipment. Everything else, he did himself with his boys assistance, including rewiring the house, rerouting gas lines, fixing the plumbing, repairing our slate roof, carpentry, constructing brick patios, pouring concrete walkways, gardening (of course!), flooring, felling 150-foot oaks, fixing anything with a motor or an engine, and on and on. He even, at times, hand-built sofas and chairs, sewing the upholstery himself.