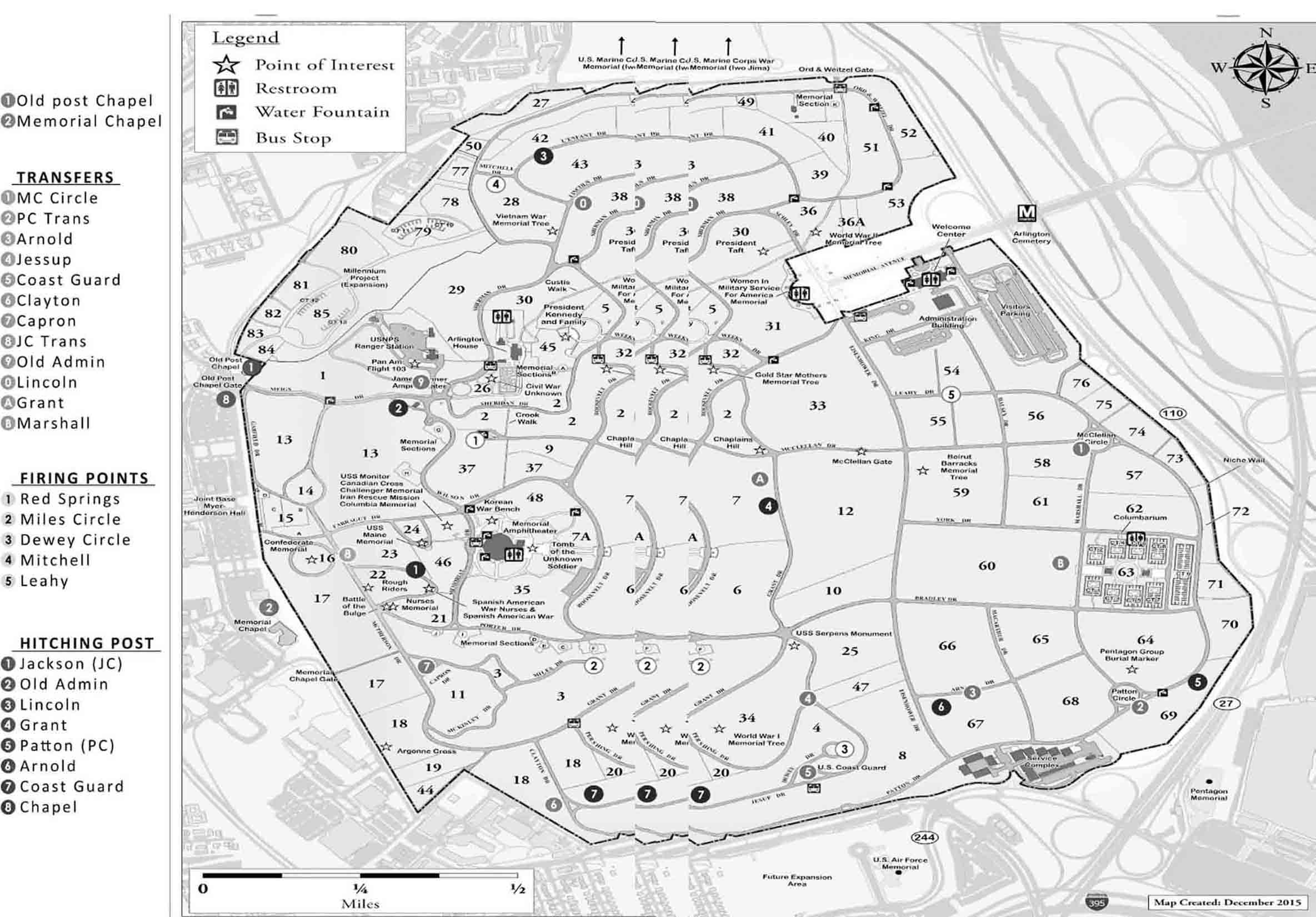

Old Guard soldiers carry a laminated copy of this map in their ceremonial caps. Note the legend on the left-hand side: Transfer Points for the transfer of the casket from the hearse to the caisson, Firing Points for the Presidential Salute Battery, and Hitching Posts for the Caisson Platoons horses.

The Old Guard

E very headstone at Arlington tells a story. These are tales of heroes, I thought as I placed the toe of my combat boot against the white marble. I pulled a miniature American flag out of my assault pack and pushed it three inches into the ground at my heel. I stepped aside to inspect it, making sure it met the standard that we had briefed to our troops: vertical and perpendicular to the headstone. Satisfied, I moved to the next headstone to keep up with my soldiers. Having started this row, I had to complete it. One soldier per row was the rule; otherwise, different boot sizes might disrupt the perfect symmetry of the headstones and flags. I planted flag after flag, as did the soldiers on the rows around me.

Bending over to plant those flags brought me eye-level with the lettering on those marble stones. The stories continued with each one. Distinguished Service Cross. Silver Star. Bronze Star. Purple Heart. Americas wars marched by. Iraq. Afghanistan. Vietnam. Korea. World War II. World War I. Some soldiers died in very old age; others still were teenagers. Crosses, Stars of David, Crescents and Stars. Every religion, every race, every age, every region of America is represented in these fields of stone.

I came upon the grave site of a Medal of Honor recipient. I paused, came to attention, and saluted. The Medal of Honor is the nations highest decoration for battlefield valor. By military custom, all soldiers salute Medal of Honor recipients irrespective of their rank, in life and in death. We had reminded our soldiers of this courtesy; hundreds of grave sites would receive salutes that afternoon. I planted this heros flag and kept moving.

On some headstones sat a small memento: a rank or unit patch, a military coin, a seashell, sometimes just a penny or even a rock. Each was a sign that someonemaybe family or friends, perhaps even a battle buddy who lived because of his friends ultimate sacrificehad visited, and honored, and mourned. For those of us who had been downrange, the sight was equally comforting and jarringa sign that we would be remembered in death, but also a reminder of just how close some of us had come to resting here ourselves. I left those mementos undisturbed.

After a while, my hand began to hurt from pushing on the pointed, gold tips of the flags. There had been no rain that week, so the ground was hard. I questioned my soldiers how they were moving so fast and seemingly pain-free. They asked if I was using a bottle cap, and I said no. Several shook their heads in disbelief; forgetting a bottle cap was apparently a mistake on par with forgetting ones rifle or night-vision goggles on patrol in Iraq. Those kinds of little tricks and techniques were not briefed in the days written order, but rather get passed down from seasoned soldiers. These details often make the difference between mission success or failure in the Army, whether in combat or stateside. After some good-natured ribbing, a young private squared me away with a spare cap.

We finished up our last section and got word over the radio to go place flags in the Columbarium, where open-air buildings contained thousands of urns in niches. Walking down Arlingtons leafy avenues, we passed Section 60, where soldiers killed in Iraq and Afghanistan were laid to rest if their families chose Arlington as their eternal home. Unlike in the sections we had just completed, several visitors and mourners were present. Some had settled in for a while on blankets or lawn chairs. Others walked among the headstones. Even from a respectful distance, we could see the sense of loss and grief on their faces.

Flags adorn every grave site in Arlington National Cemetery over Memorial Day weekend. Old Guard soldiers place the flags on the Thursday before Memorial Day.

Arlington National Cemetery

Once we finished the Columbarium, mission complete came over the radio and we began the long walk up Arlingtons hills and back to Fort Myer. In just a few hours, we had placed a flag at every grave site in this sacred ground, more than two hundred thousand of them. From President John F. Kennedy to the Unknown Soldiers to the youngest privates from our oldest wars, every hero of Arlington had a few moments that day with a soldier who, in this simple act of remembrance, delivered a powerful message to the dead and the living alike: you are not forgotten.

The Thursday before Memorial Day is known as Flags In at Arlington National Cemetery. The soldiers who place the flags at every grave site in the cemetery belong to the 3rd United States Infantry Regiment, better known as The Old Guard. Since 1948, The Old Guard has served at Arlington as the Armys official ceremonial unit and escort to the president.

I walked through Arlington for Flags In with The Old Guard in 2018. What better way to show the nation and our fellow soldiers that we care and we never forget, observed Colonel Jason Garkey, the regimental commander. As we walked along streets named for legends like Grant and Pershing, he added, This mission is really important for The Old Guard, too. Its the only day of the year when the whole regiment operates together. It gives all my soldiersall my mechanics and medics and cooksa chance to come perform our mission in the cemetery.

Flags In carries a special meaning for our citizens, too, judging by our conversations that afternoon. Col. Garkey greeted every civilian who approached us. Most were curious about the soldiers they saw walking across the cemetery. As he explained Flags In and The Old Guard, without fail they expressed their fascination and gratitude. In Section 60, we encountered families and friends paying early Memorial Day visits to their loved ones. Col. Garkey thanked them for their sacrifice, and they thanked him for his service and for remembering their fallen heroes. He never mentioned that those were his soldiers or that he had planted flags that day at the graves of his own friends and mentors.

My turn at Flags In came in 2007 during my own tour at Arlington. I had joined The Old Guard a couple of months earlier, after serving a tour in Iraq with the 101st Airborne Division. My path to The Old Guard was unusuallike my journey into the Army itself.

It began the morning of 9/11 in a law-school classroom. In those days before smartphones, we did not learn that America was under attack until class ended, almost an hour after the first airplane hit the World Trade Center. But my life changed in that moment. I knew the life I had anticipated in the law was over. I wanted to serve our country in uniform on the front lines. I finished school and worked for a couple of years to repay my student loans, time I also used to get prepared physically and mentally for the Army. It took my recruiter by surprise when I told him that I wanted to be an infantryman, not a JAG lawyer. To his credit, he signed me up and shipped me out, setting me on the path to Iraq. After more than a year in training, I joined the 101st in Baghdad in 2006, taking over a platoon of Screaming Eagles. We conducted raids, laid in ambushes, dodged roadside bombs and sniper fire, and sorted out the dead in a vicious sectarian war. And at the end of that tour, to my surprise, the Army gave me orders to The Old Guard, even though I had not applied to the all-volunteer regiment.