This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1945 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2014, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

John Dooley Confederate Soldier

HIS WAR JOURNAL

Edited by Joseph T. DURKIN , S.J. Professor of American History, Georgetown University

Foreword by DOUGLAS SOUTHALL FREEMAN Author of R. E. Lee , Lees Lieutenants , Etc.

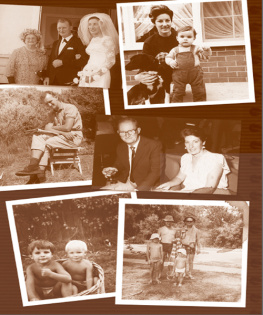

CAPTAIN JOHN E. DOOLEY, C.S.A.

FOREWORD

THE lesser narratives of the War between the States sometimes explain the larger. Nearly always the problem of the historical student is not the what but the why, not the event, but the reason for it. In many such cases, official documents do not give the solution. The reporting officer may have delayed so long the preparation of his account that his explanation of a particular decision or the cause of a critical twist of action became confused in his mind. More often, obscurities and omissions covered failures. On occasion, too, if the reported outcome of a battle conforms too closely to an officers elaborate account of what he intended to do, suspicion is aroused that afterthought is presented as forethought. To avoid the temptation of pretending that the contingent was part of the original design presented a test, always, of a soldiers intellectual honesty.

Where, for any of these reasons, the report of a Union or Confederate fails to answer the students question, the narrative of a junior officer or the diary of a private may. A rain that is not mentioned in the report of the commanding General may have turned a road across a lowland into a quagmire. Unconfessed failure of commissary officers to get food to the front, a bad road block, lack of water, stifling dust on a long march, the sore feet of men who had to march over hard roads after days on sandy byways these circumstances, which may have decided battles, occasionally are set forth, sometimes casually, in the personal narratives of inconspicuous soldiers.

To such narratives, also, a student must turn if he is to understand the morale of an army. From those narratives one often gets color and incident and a thousand touches that lighten the unrelieved seriousness of official reports. Half-a-dozen narratives, written by privates or sergeants of Lees Army, are as important as the collected reports of any brigade commander or of almost any divisional leader. One thinks particularly of John O. Casler, of William W. Chamberlaine, of David Johnston, of Edward A. Moore and of John H. Worsham.

Most acceptably, to these familiar books, and to others of the same type, there now is added this narrative of a soldier of the First Virginia Infantry, Kempers Brigade, Picketts Division, First Corps Army of Northern Virginia. The journal of John E. Dooley begins immediately after the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Aug. 9, 1862, and closes so far as it describes combat, with the charge of July 3, 1863, at Gettysburg. There is an interesting and wholly authentic addendum on prison life, but the most valuable part of the story John Dooley tells from the viewpoint of a private and then of a company officer is that which covers the eleven red months of offensive operations between the Rappahannock and the Susquehanna. It was the period of the greatest achievements of Lees Army. In all of them, except Chancellorsville, the men of Kempers brigade had an honorable role, sometimes a conspicuous part. As narratives by soldiers of Picketts Division are few, that of John Dooley complements Johnstons Story of a Confederate Boy in the Civil War and deserves the editorial care Father Durkin has spent on it.

The dual form of the manuscript, a diary and an expanded narrative, is one used by several Confederate writers. In Father Durkins presentation of the text, about four-fifths of the entries are from the original diary. The passages elaborated by Captain Dooley are distinguished easily. In some published diaries, this is not always possible. George M. Neeses Three Tears in the Confederate Horse Artillery to cite a single exampleis a readable narrative concerning a branch of the service poorly documented; but the contemporary entries and the subsequent rewriting and adornment so impair the historical testimony that it puzzles the reader. Captain Dooleys additions to his diary were made, fortunately, while the events themselves still were fresh in a youthful mind. He probably erred in attempting to rewrite his journal, because he occasionally indulged in heroics; but he did not mislead himself nor will he mislead his reader with incidents that imagination draped when time and failing memory had left fact dim and drab.

The vice-Captain Dooley avoided without difficulty has misled many an autobiographer and many a historical writer who relied too confidently on personal narratives written late in life and long after the events. Individual memory varies much. No historical canon, therefore, can be applied uniformly. In general, experience has shown that incidents of a dramatic character, first put in print two decades or more after their occurrence, should not be accepted unless confirmed by some earlier authority. This is particularly true in those instances where a public man who made numerous speeches subsequently wrote them down. So apt was the orator to adorn the tale that the usual historical critique may not suffice to save the reader from acceptance of error. In the case of John Dooley, his flourishes, which are not numerous, are literary and not factual. They do not impair a narrative which Father Durkin has edited with so much judgment and scholarship that one gladly steps back, so to say, and presents him to the audience.

D OUGLAS S OUTHALL F REEMAN