This edition is published by ESCHENBURG PRESS www.pp-publishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books eschenburgpress@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

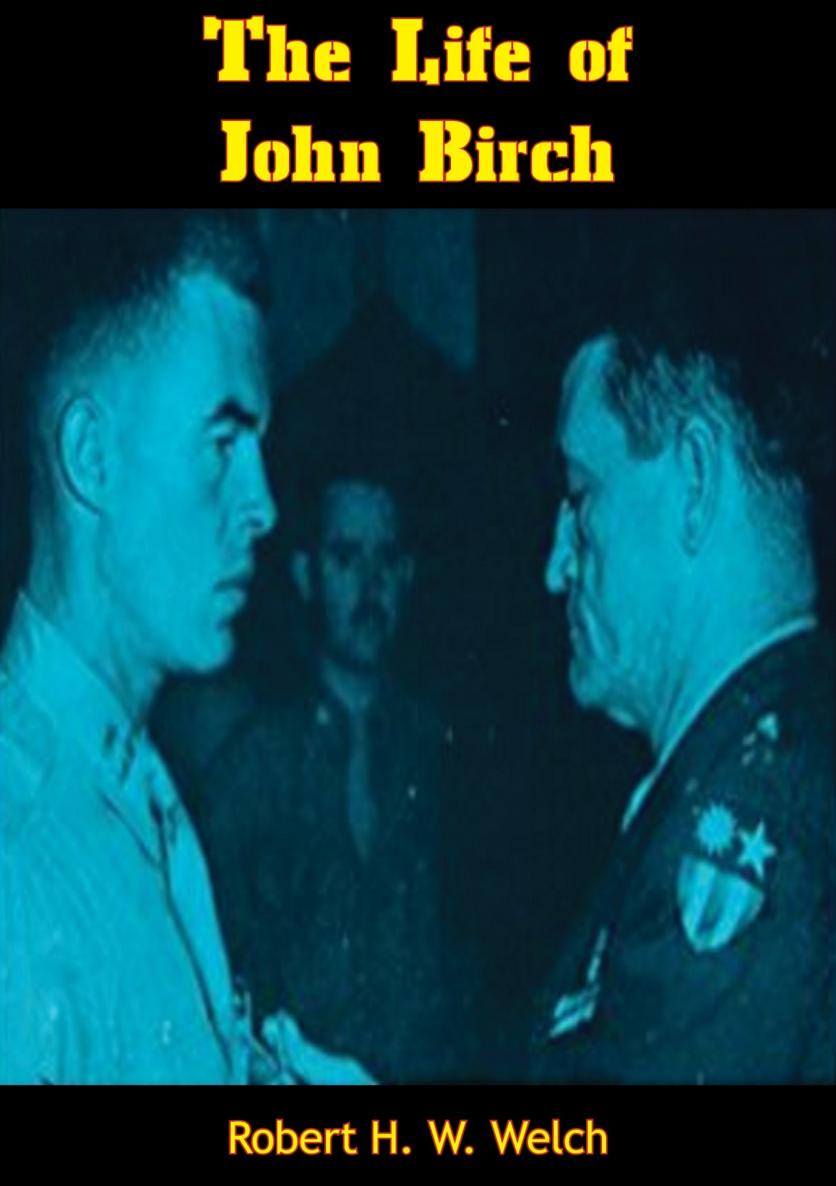

Text originally published in 1954 under the same title.

Eschenburg Press 2017, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

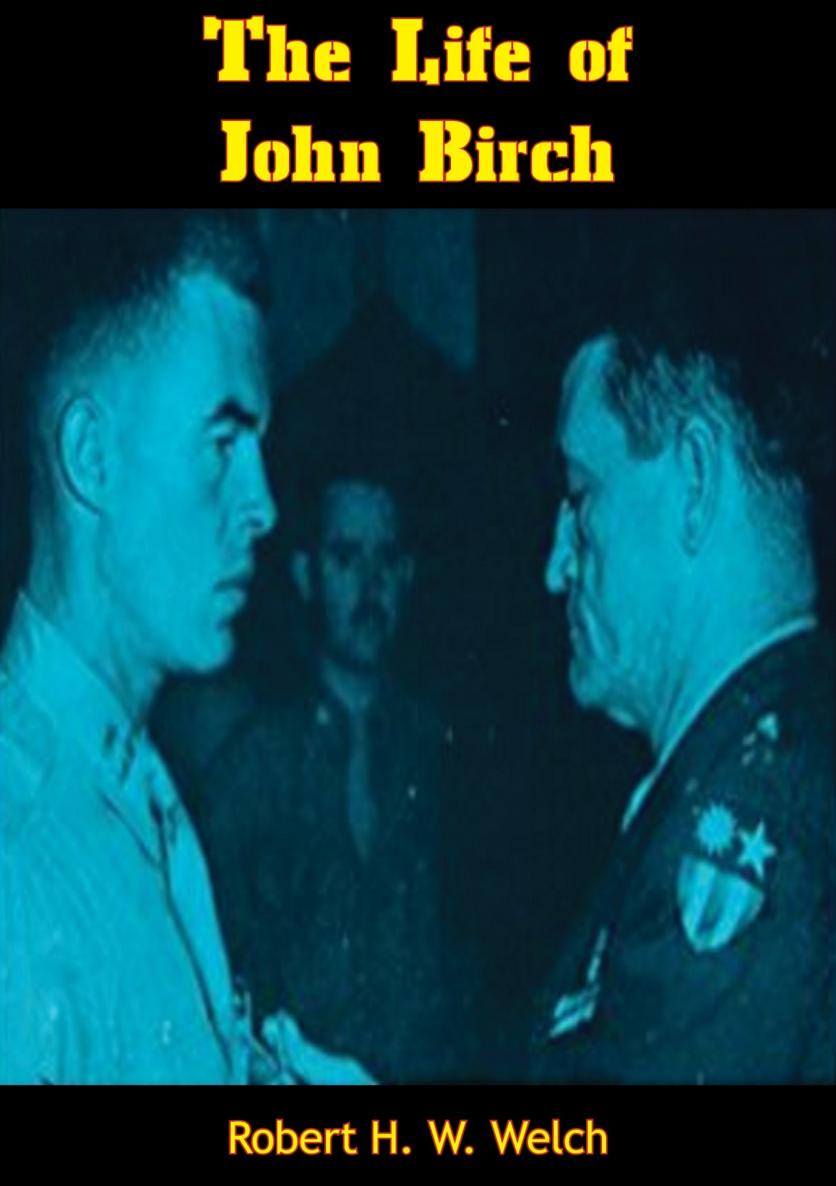

THE LIFE OF JOHN BIRCH

In the Story of One American Boy, the Ordeal of His Age

BY

ROBERT H. W. WELCH, JR.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

Contents

TABLE OF CONTENTS

DEDICATION

For

JOHN T. BROWN

with admiration

and kindest regards

FOREWORD

But on one mans soul it hath broken,

A light that doth not depart;

And his look, or a word he hath spoken

Wrought flame in another mans heart.

Until a little more than a year ago I had never heard of John Birch. And the links of transmission, through which the impact of this young man reached me, were thin and strained. A more tenuous chain of influence could hardly have been imagined by OShaughnessy while writing the above lines of his great ode.

All alone, in a committee room of the Senate Office Building in Washington, I was reading the dry typewritten pages in an unpublished report of an almost forgotten congressional committee hearing. Suddenly I was brought up sharp by a quotation of some words an army captain had spoken on the day of his death eight years before. Interest in the quotation soon led me to the incident with which the following narrative begins. From then on the light of John Birchs actions gradually became greater than the light of his words, and neither would depart. With regard to both, I had to learn all I could of their source and their circumstances. This small book is the result of my search.

Somewhere in Goethes thousands of pages appears the beautiful line: Alle menschliche Gebrechen sbnet reine Menschlichkeit . Pure humanity atones for all human crimes and weaknesses. As of today this may be too optimistic a balance sheet. The debit side of the ledger is heavy with mass murders and inhuman tortures, with blasphemy and treason and felonies and cruelties, so despicable in degree and so widespread in practice as to prompt a feeling of despair. Even the purity of character and nobility of purpose of a John Birch can atone for only a small part of so much human vileness.

But there is strong encouragement in finding so firm an entry on the credit side. For the fact that cultural traditions and ethical forces still at work can produce one such man is clear proof that they are still producing others like him. Of the slowly built hereditary and environmental molds, into which such youth were poured, many have now been smashed altogether, and many more have their sidewalls badly cracked; but many still remain unreached by the stresses of political tyranny and the erosion of moral anarchy around us. The output of these molds can still save our civilization.

It is no accident that you also, who now read these lines, have probably never heard of John Birch before. That small victory of our Communist enemies, in consigning him to temporary oblivion, cannot now be undone. But even with my plodding skill bogging down my bounding purpose, I believe that you will long remember him after finishing these short chapters ahead. And his memory will add, in some small measure, to your hope and your inspiration.

ROBERT H. W. WELCH, JR.

Belmont, Massachusetts

February 22, 1954

ITHE RESCUE OF COLONEL DOOLITTLE

THE TIME IS AN EVENING IN APRIL, 1942. WE HAVE been at war with Japan four and one-half months. Colonel Doolittles flyers have just startled themselves, the Japanese, and the world with their token bombing of Tokyo. But the planes have no place to land within their fuel range. For China has been at war with Japan four and one-half years . The coastal provinces of China are full of occupation troops, which at this very time are beginning new advances inland. The three airfields most counted on have all been bombed, whether through a leak in Washington as suspected by General Stilwell or solely by the accidents of war. At any rate, Doolittle and his fellow pilots simply fly their planes to the Chinese mainland, and over it as long as their gasoline holds out. They then come down with a crash landing, or by parachute.

The place is a cheap restaurant in a village by a river, near the western boundary of Chekiang Province. One of the customers is a young American. He is dressed in cheap native clothes, and speaks the native dialect. He is eating the cheapest native food, by habit as well as by thrifty instinct. For while, at the minute, he has a little more money than usual, he has been living on two dollars per month for the past several months. (Later this ability, gained by hard experience, to subsist on bamboo shoots and the cheapest red rice, is to prove of great value when he becomes the first American ever to live and work in the field with a Chinese army. Later, he is to prove his remarkable proficiency at disguising himself and melting away undiscoverably into the native population. But tonight he knows nothing of this future.) Fortunately, while not conspicuous, he is making no attempt to hide his own nationality.

The other patrons of the restaurant are all Chinese. One of them, on his way out after a brief meal, brushes against the stranger as if by accident, and manages to whisper, in Chinese: If you are an American, please follow me. The stranger, as soon as he dares, also rises and leaves. The incident goes unnoticed by the other diners.

Outside, the American is taken by his self-appointed guide to a small covered riverboat, casually and inconspicuously laid up alongside the rivers bank. In that boat he finds Colonel James H. Doolittle, who has been hidden and brought this far by Chinese patriots. This is the first American Doolittle has seen since his raid. The young man is able not only to get Colonel Doolittle safely into free China, but is instrumental in rounding up and saving a number of the men from several of the other planes. Without him it is doubtful that any of these flyers, or their commander himself, would have escaped capture and torture by the Japanese.

I ran across this very small but unusual pebble on the beach of history while looking for some larger and entirely different rocks. It puzzled me, and prompted several questions, (1) Who was this young American? (2) How did he happen to be where he was at this exact and opportune time? (3) What happened to him afterwards? As I dug for the answers they soon led me to more important questions: (4) Why was so heroic, brilliant, and consecrated a patriot so completely unknown in America? And (5) What was the significance of his lifeand death? What I found out on all five points is outlined, in part, below. But it is the last two questions that give weight to the whole inquiry. For, as Senator Knowland has stated publicly, if the story of this young man had been known and understood, it could have made a huge difference in our attitude and the circumstances that led to our engagement in Korea.